By Bill Hirschman

By Bill Hirschman

In the six and a half years since the landmark Coconut Grove Playhouse shuttered, irreplaceable theatrical history has festered in a fetid, crumbling structure, endangered by everything from larcenous-minded vagrants to Florida’s infamous mold-rich climate.

Expensive hand-made costumes, original set designs, playbills touting George C. Scott to Denzel Washington and Ethel Merman to Liza Minnelli, video recordings of productions, memorabilia reflecting the Grove hosting the 1956 American premiere of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting For Godot.

All of it and more languished while the Playhouse board, its $4 million worth of creditors, developers, state and county officials sparred over whom, if anyone, would take over the facility, if ever.

But in a third-act development worthy of a melodrama last fall, two groups rescued the ephemera of the most ephemeral of art forms. Actors’ Playhouse in Coral Gables and the University of Miami library’s special collections division have invested considerable time and manpower to retrieve some of the Grove’s treasures, officials confirmed this month.

“I consider them civic heroes,” said Michael Spring, director of Miami-Dade’s Department of Cultural Affair.

While the fate of the Playhouse itself remains in doubt until sometime next month, most of the documents were saved – enough photographs, scripts, videotapes, scrapbooks, posters, headshots, marketing materials and business correspondence to fill 800 boxes.

Manuscripts Librarian Beatrice Skokan leads a team of archivist / All photos except exterior shot by Duvy Argandona

“It was not as bad as we thought it would be,” said Cristina Favretto, head of UM’s special collections who led the reclamation with manuscript librarian Beatricre Skokan. “Some kind of theater God was there that we got there in time.”

The elements did damage uncalculated expanses of costumes, props and equipment, but Actors’ Playhouse and former Grove costumer Ellis Tillman carefully selected pieces including two bins of clothing.

The librarians salvaged paper records that will be open to the public after a three-year restoration project that could cost more than $100,000, both figures only rough estimates. Actors’ Playhouse may reuse the costumes, a few props and a few pieces of equipment in local productions, said Executive Producing Director Barbara Stein.

“The goal was to find a responsible place where those materials could be used,” Spring said. “It’s not about money; it’s about history.”

Margaret M. Ledford, now a freelance director who worked on the Playhouse staff in its final days, said, “The whole building has that feel: You knew you were part of something long before you — and you hoped that would live long after you.”

The rescue has its roots in the theater officials’ fear that if the state took over the property and sold it to a developer, the new occupants would simply toss out what they couldn’t use, Spring said.

About two years ago, the University of Miami’s special collections staff began talking with people who run the annual Coconut Grove Arts Festival. The festival officials thought the playhouse’s contents might be a good fit since the university already houses extensive records about the history of the Coconut Grove neighborhood, Favretto said.

Conversations continued with Spring and Shelly Spivak, chairman of the Grove’s board. Then, talk that the state was going to take possession and that demolition of the building might even be possible spurred the players to act quickly. The Grove board donated the papers to the university and Spring arranged a “long-term loan” of the costumes and other physical possessions to Actors Playhouse, he said.

It was a daunting undertaking, if only because of the expense. Each of the 800 specially designed storage boxes cost $14 each – not counting the acid-free folders to contain the papers.

“When we bring in a collection of this scope and size, it’s a huge commitment,” Favretto said. “But we thought ‘It’s Miami history, it’s Florida history, it’s Grove history, the Grove is where Waiting For Godot had its American premiere. Who could say no to that?”

“When we bring in a collection of this scope and size, it’s a huge commitment,” Favretto said. “But we thought ‘It’s Miami history, it’s Florida history, it’s Grove history, the Grove is where Waiting For Godot had its American premiere. Who could say no to that?”

Accounts differ somewhat about the building’s precise condition and structural integrity although it is likely to be outlined in the state’s detailed appraisal that may be released when the property is formally offered to interested parties sometime next month.

But no one questions that the once elegant show palace had severely deteriorated when the library and theater staffers entered Oct. 8 and 9 to sort, pack and direct movers.

Stein said, “The theater had been vacant for so many years with apparent vagrants camping out at times. The electrical was not on in all areas making it spooky to locate materials that could be salvaged. Humidity had poorly affected costumes, but we were able to save some costumes that were unusual and had little damage.”

The roof leaked, accounting for water damage. Vagrants had lit fires inside. Toilets had not been flushed. There was less grafitti than expected, but vandals looking for cash had smashed in computer monitors.

The environment was spooky at times. The boarded up first floor was pitch black although sunlight peeked through on the second and third floors, so the first crews doing reconnaissance used flashlights to explore the area.

Because the Grove staff was simply ordered to take their personal belongings, leave the premises and the doors were locked, it felt like the Mary Celeste , a ghost ship discovered abandoned at sea, the archivists said. “It was like people just left,” Skokan said, “The bed covers in the apartments were thrown open. There were cups there with dried coffee. It’s as if everybody just walked out.”

The set to the last show, a revival of Sonia Flew starring Lucie Arnaz, was still standing on stage complete with a working kitchen.

“It was like being in Pompeii,” Favretto said.

The interior was unusually hot and humid for October and workmen brought in lights and fans. “We did have an engineer for safety and we did walk gingerly at first because we didn’t know what we were stepping on or what we were stepping in, but eventually we were just tramping up and down the stairs,” Skokan said.

They had no time to catalog anything, only to note on each box what office or room the contents came from. Therefore, even now, they only have a rough idea of what they brought back.

But among the boxes are the complete business records including orders for supplies. While less “sexy” than the scripts and photos, the paperwork — down to the “do not call list” for the telemarketers — document the extreme detail of work required to run a regional theater and produce a show, even “the efforts to finding the right cups for a show. The dedication to the deep level of detail is moving,” Favretto said.

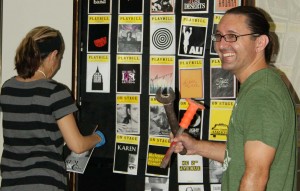

A major treasure are the playbills. The Playhouse’s last producing artistic director, Arnold Mittelman, had collected and mounted on two lobby walls behind Plexiglas what he believes is every program from every production in the Playhouse’s half-century history, although some may be copies. Favretto, who has a mlove of theater, cut her hand while trying to retrieve the documents.

A major question mark surrounds the videotapes that the Playhouse made of productions for rehearsal and archival purposes, uses strictly outlined by agreements with the unions. Many had already been donated to the New York Public Library’s Theatre on Film and Tape collection at Lincoln Center. But others were found by Skokan’s crew and no one knows what condition they’re in.

Everything was boxed up and then stored through November in a freezer to kill whatever might be hiding inside, then everything was taken to the University of Miami library’s climate controlled storage off campus.

Actors’ Playhouse had to be more selective due to a lack of storage and limited resources for restoration. Tillman sorted through hundreds of pieces of clothing that he and his staff built, bought or supervised. Much of it was too far gone to be saved and even more were pieces that Actors’ Playhouse didn’t need because they were contemporary clothing easily found in thrift shops.

The same criterion was used for props. The Coral Gables theater had no need for shelves and shelves of glassware, plates and bric-a-brac. They opted for about “two yards” of props such as old telephones and cameras, plus some simple equipment and tools, Stein said. They found moth-eaten rugs and thousands of pieces that would have required “five years of packing,” she said.

All that is still in there.

One of the key challenges will be assessing what is in the boxes. It would take years to catalog the individual items. Skokan and her staff will essentially classify the material into topics and sections that will intuitively make sense to researchers and the merely curious. It helps that the library staff labeled the boxes they removed noting the locations such as “marketing department.” It can take 10 hours to classify a box’s contents and place them in acid-free folders or acetate sheets and replacing rusting paper clips with stainless steel models. Using staff and students, it costs about $15 an hour per box.

Some materials will be taken to a preservation department that takes damaged papers and stacks of photos sticking together, separates them and puts them into plastic sleeves. Because of the added cost, the staff selects which materials are important enough to save that way.

Some materials will be taken to a preservation department that takes damaged papers and stacks of photos sticking together, separates them and puts them into plastic sleeves. Because of the added cost, the staff selects which materials are important enough to save that way.

Nothing will be digitized because the library avoids copyright problems by not copying anything created after 1923. But visitors to the collection will be able to shoot photos of the materials when they become available for public use.

Starting out as a movie theater in 1926, the Spanish rococo building on the southwest corner of the Coconut Grove business/entertainment district has been repeatedly remodeled under several ownerships while becoming one of the nation’s leading regional theaters that emerged after World War II. Producers like Zev Buffman, Robert Kantor, Jose Ferrer and, after 1985, Arnold Mittelman mounted their own shows, hosted national tours and even provided a home for works being developed for Broadway.

The shows and the performers reflected a time when fading stars and supporting actors in film and television were able to headline major stage productions that they would never have the chance to attempt in New York. Some were triumphs and many were flops. Some were unadventurous fare; others reflected the latest thought-provoking hit from Broadway.

Among the legendary productions was the first American version of Godot, starring Tom Ewell and Bert Lahr, an evening that left many playgoers confused because it wasn’t the comedy those stars were usually seen in.

There was the troubled opening night of A Streetcar Named Desire in 1956, belatedly starring Tallulah Bankhead, the actress who Tennessee Williams originally wanted for the Broadway premiere. Bankhead famously camped up the part for the many gay men in the audience, but scaled it back after Williams criticized her. A Broadway-bound revival of Finian’s Rainbow in 1999 died a-borning and the pre-New York tryout of the musical version of Urban Cowboy in 2002 was a major debacle.

“It’s not just the building that’s historic; it’s what has happened there. It’s really the spiritual activity there,” Spring said.

Financial woes mounted with cuts in state funding and diminishing audiences. The three-story edifice at 3500 Main Highway was suffering structural problems. According to one report disputed by Mittelman, sea sand mixed in the concrete exterior had created a chemical reaction to erode the steel beams. But other employees have reported holes in the ceiling and marble falling off the walls.

In its 50th season in the spring of 2006, the company cancelled Sonia Flew with Lucie Arnaz and closed the theater for a few days. Subsequent donations by Arnaz and Bacardi Ltd. allowed the drama to open and run an abbreviated two weeks. But as soon as it was over, the doors closed. Mittelman was locked out, then the staff. Despite the board’s murmuring about plans to reopen, it never did.

The state of Florida had taken ownership in 1980 by purchasing a $1.5 million mortgage and contracted with the Playhouse board to run it until transferring the title to the board in 2004 with the requirement that it be operated as a theater. Last October, the state retrieved the title because the property was dormant.

The property is expected to be offered for purchase in February to state agencies and universities. If those entities don’t jump on it, the county government has been anxious to take it over and build a new theater on the parking lot. The exact plans for the existing building – designated a historic site by the City of Miami — are nebulous.

But for the meantime, some of its precious contents are safe and that’s what is important to Skokan.

“Two hundred years from now, I want these to be available,” she said.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design

Pingback: Actors Playhouse and UM team up to save artifacts from shuttered Coconut Grove Playhouse | Broward News and Entertainment Today

Pingback: EPHEMERA RESCUE | 9 Miles Of Ephemera