Who are we? Where do we want to go? What’s standing in our way? How do we prevail? The dwindling days before the season gears up are a prime time for us all, audiences to artists, to invest in a tough self-examination of South Florida theater.

We suggest concrete answers in three extensive essays this week. The opinions are ours, but they result from more than 30 lengthy interviews and dozens of shorter ones with professionals in the region and across the country who we will list at the end of each article. In the first part on Monday (click here), we defined precisely what South Florida theater is and can be. The second on Wednesday (click here) dissected the handicaps, shortcomings and challenges. The last and longest essay today offers potential solutions.

It’s unlikely you’ll agree with half of what is suggested. Some observations will seem obvious. Some may even be wrong. Some may get you angry. Good. We’re throwing chum in the water to start an overdue conversation in lobbies, dressing rooms, board rooms and cyberspace. Talk back to us. We want your signed responses in the comments sections at the end of the articles, or in your own essays that we will consider editing and publishing if you send them to bill@floridatheateronstage.com.

By Bill Hirschman

In the film Shakespeare In Love, the producer says theater’s “natural condition is one of insurmountable obstacles on the road to imminent disaster… Strangely enough, it all turns out well.” When asked how, he says, “I don’t know. It’s a mystery.”

It’s a delightful scene. And it’s wrong.

We may not know all the answers, but we know some of them. We’re trying some even now.

Best of all, we are armed with one inestimable weapon: passion. Don’t scoff. That’s not a saccharine homily from a Disney musical. You didn’t see the fervor that suffused nearly every interview we had with actors, designers, directors, administrators and supporters. Some of the joy was mixed with anger and an unspoken feeling of betrayal; some of the hopefulness was tempered by disappointment and fear. But the gleam in the eyes and the power in the voices of such disparate partisans as Arturo Fernandez of Ground Up & Rising and Scott Shiller of the Arsht Center evidenced an energy, idealism and belief in the worth of art.

What came clear from months of study and thought was the need for – and the likely success of — audiences and artists dredging up the sheer will to escalate their investment.

Of course, there is no one-size-fits-all solution or even series of solutions. Some of the problems facing the Maltz Jupiter Theatre are different than those facing Actors Playhouse in Coral Gables, although they both mount large-scale musicals. The course is for each county, each community, each company to pull what works best for them from the menu of options that we’re about to explore.

I’m Still Here: Awareness

Theater must engage.

In the last essay, we hammered that an immediate priority must be injecting theater into the consciousness of the general public, the budget-controlling policymakers, the philanthropists, a younger audience and tourists. The crucial task is to build the hunger for theater in our communities, even a sense of entitlement that theater is part of the cultural fabric.

That, of course, means marketing, and while marketing usually means money that many troupes don’t have, some of the solutions primarily require inventiveness, elbow grease and resolve.

It takes money to buy billboards, but it doesn’t cost anything for the chairman of the board to speak at a Chamber of Commerce luncheon about how theater is an economic driver in the community. It requires little to enlist 20 high school drama students to audit design meetings, set construction and rehearsals to create a cadre of bloggers who will spread word of a show far beyond an old email list of Baby Boomers.

Obviously, the Internet has become an attractive tool, primarily because it’s free other than the internal staff time. But it needs to be used more inventively.

Theaters need to pick up on best practices discovered by other regional theaters such as the Denver Center for the Performing Arts. It’s not just sending emails and posting on Facebook or Twitter. It’s the interactive multi-media videos, contests and other ploys that attract people. Some companies like the Maltz have aggressively explored options like putting up buzz-building micro-sites – pages with backstory and behind-the-scene videos for each production to intensify audience interest.

Several local theaters are experimenting with videos that can go virally, but most are pretty dull. In contrast, check out Slow Burn Theatre Company’s promotional video by clicking here. (http://www.facebook.com/photo.php?v=10150895582561846) Additionally, Google Analytics provides several levels of drill-down information about who is visiting your website, providing free clues to your audience’s demographics and whether certain promotions are gaining traction.

Some theaters with predominantly older audiences only half-heartedly use the Internet, believing their patrons aren’t online. Horse puckey. See how many seniors are scrolling through their emails and checking out web sites on their smartphones while waiting for the house lights to go down.

But Internet marketing shares the same limitation as brochures sent to a snail mail list: It’s preaching to the choir. While advertising gurus say repeated contacts translate into future sales, theaters need to discover how to market on the cheap to the people who are not already in contact with the theater.

For instance, Florida has a rich built-in market that is rarely tapped: tourists. In Chicago, roughly a fifth of the five million tickets are sold to tourists and conventioneers each year. Even without a beach as a draw, tourists flock annually to the Stratford Shakespeare Festival in the-middle-of-nowhere Canada or the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in remote Ashland just to see theater.

The Arsht and the Broward Center for the Performing Arts have experimented with outreach to the tourists. But redoubled efforts are needed to put already-printed lobby cards and mailers in the attraction racks in hotel lobbies. Concierges should suggest theater as part of a dinner package for sun-burned visitors stymied by the evening rainstorms. Hotel managers should mention theater in guests’ welcome materials or to packets sent to convention planners.

I’m Reviewing the Situation: A Few More Ideas

An abbreviated list would also include:

* Mass Media: Many theaters have given up too easily trying to get better media coverage, especially from television. They’ve been rebuffed by editors because their story ideas would bore anyone except insiders. But overtaxed journalists love it when a story that is interesting to a general audience is laid in their lap. Just be certain it has visual elements that can be filmed or photographed. Want to pitch August: Osage County? It’s not a three-hour Pulitzer Prize winner lauded for its insights and language; it’s a slugfest of family dysfunction that makes the Real Housewives look like lightweights. That can be illustrated with a couple of choice clips from rehearsals. But theater staffs must make direct contact with TV news directors and print section editors (even occasional face to face contact) with specific and unique story ideas that they would actually like to watch themselves.

* Niche marketing: Some theaters are marketing the merits of a particular show rather than the company itself as brand. Take a clue from Tyler Perry. For decades, Perry’s theater comedies geared to black audiences were marketed through African American churches. Spend the limited marketing dollars targeting promising audiences. For Death and Harry Houdini, the Arsht partnered with the local Brotherhood of Magicians. When the Maltz does Amadeus this year, it would make sense to hook up a promotion with a classical music radio station.

* Promote the actors as a brand: Currently, some advertising does not mention the actors or director. But just like film audiences, some regular patrons will go see a show simply because they’re admirers of the work of Todd Allen Durkin or Angie Radosh or J. Barry Lewis.

* Carbonell Awards: A tug of war has ensued for years between insiders wanting to keep Theater Prom as an insular intimate industry party and those who want it to be a high-profile public blowout. But clearly, the Helen Hayes, the Jeffersons and the Tony Awards have increased Theater’s visibility in the general populace’s cognition. Those programs get atypical media coverage, even on television. Fans in those communities, not just theater workers, look forward to attending the ceremonies. The primary roadblocks are the cost and logistics of marketing the ceremony and adding headliners who will attract a larger audience, a facet that insiders have openly resented in the past.

Come To The Cabaret: Advanced Marketing

One major initiative is being explored by tourism officials and the Broward Center for the Performing Arts — creating a major cultural event that will draw people from around the country and even around the world, like Miami Beach’s Art Basel. Whether or not this is a theater-centric event, it can be designed with theater built directly into its weave. Again, we have international name recognition already. Who even knows where Ashland is?

More achievable in the short run is “Event Marketing,” which targets Millennial and Boomer audiences accustomed to spending an entire evening out. Theaters are trying to engage their potential audiences by making the play one part of a packaged evening with stops before and/or after the theater. This is more structured and elaborate than the current practice of simply providing a discount at a nearby restaurant by showing a ticket stub (hours after dinner is over, we might add). Actors Playhouse combined Real Men Sing Show Tunes with a pub crawl. Mosaic Theatre encouraged tailgate parties before Lombardi as well as talkbacks with noted sports figures rather than just the actors.

A subset of “The Event” is “The Buy-In.” It narrows the gulf between audience and the art by allowing them to witness the process of their theater being made. In the past, this has been restricted to staged readings. But that is changing. The new Outré Theater Company in Boca Raton is planning to sell a ticket that would provide patrons access to selected planning meetings and rehearsals. The Maltz rewards its Circle of Friends donors with a meal and a field trip to tour the costume shop or watch the carpenters at work or interact with the visiting artists, anything to increase their emotional investment in the show. Seeing that sound effects and lighting don’t just appear magically, but result from hard work makes them feel part of the creative process.

What’s Playing At The Roxy?: 21st Century Programming

Watching the Goodman Theatre’s transcendent production of O’Neill’s epic The Iceman Cometh this summer in Chicago, one thought persisted through the 4 ½-hours, four acts with three intermissions: Mamet could have done it in half the time. Not as well. Not delivering the profound depths of elegiac tragedy. But a lot more economically.

Storytelling has changed since the days of Ned the Neanderthal, since Aristophanes and since O’Neill. While 21st Century theater absolutely must present those archetypal plays intact, modern theater must embrace that narrative is evolving and splintering into different paradigms.

It’s not contradictory that, at the exact same time, theater must emphasize its millennia-old strengths that no other medium can duplicate –experiential, immersive theatricality in tandem with the immediate connection of being in the same room with a live storyteller with a congregation of other people.

Building audiences not eligible for their AARP card requires leaning more heavily on visual, stylized theater. It needs to speak to a more attention-challenged audience that already knows storytelling shorthand from decades of watching movies. It needs to indulge in affordable theatrical spectacle that relies on imagination more than cinematic explosions such as Naked Stage’s bare bones The Turn of the Screw this summer in Miami.

The Arsht management obviously buys into stylized theatricality. This season it will import its third annual visit from the House Theatre of Chicago. The Sparrow in 2011 made it clear that some audiences hungered for such fare. Death and Harry Houdini this April sold out most performances. And finally, like it or not, the Arsht may be blurring the definition of theater with its spectacle-driven Fuerza Bruta and The Donkey Show, but it’s also bringing in an audience beyond balding greybeards. The as-yet unanswered question is whether any of those disco dancers can be enticed to see the Arsht’s hosting of Zoetic Stage’s production of I Am My Own Wife this fall.

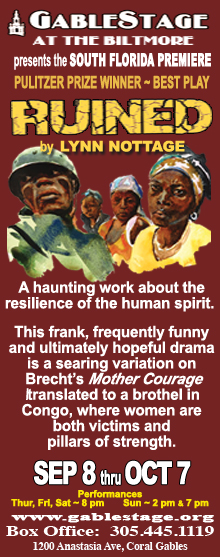

The sea change in programming needs to be eased into, but evolution is possible. Producing Artistic Director Joe Adler said that while GableStage has sought thought-provoking theater, his audience would not have stood for the profane and funny The Motherf**ker With The Hat ten years ago. Similarly, Artistic Director David Arisco has nudged Actors Playhouse audiences in Coral Gables. While 2003’s Floyd Collins was as disastrous commercially as it was an artistic triumph, Arisco has trained his doggedly mainstream audience to accept the marathon of unsettling August: Osage County and the musical Next To Normal about a family coping with bipolar disorder and electroshock therapy. Those shows succeeded, producer Barbara Stein surmises, because they were the titles that Floridians had heard about, but hadn’t seen in New York or the shows never toured here. It’s making the same bet with Other Desert Cities this spring.

As challenging and risk-taking as theater has to be to engage new audiences, consistency of quality is what keeps bringing people back. Until its meltdown last year, Florida Stage audiences returned season after season to a slate of world premieres that they knew nothing about. But they were certain that even a near-miss of a play in development would be a well-made, intriguing work. GableStage could produce Sarah Kane’s raw and rugged Blasted in 2010 because the company’s audience trusted the company’s reliability.

And while no one wants thought-provoking theater more than theater critics, there’s still a palatable need in these trying times for sheer entertainment, even mindless fun.

Children Will Listen: Growing The Next Audience

It’s old news that survival into another decade relies on growing the next audience. But while almost every major theater has a youth-oriented program, the crucial drive to engage and seduce tomorrow’s patrons sometimes gets short shrift because many theater leaders don’t perceive the need as a grassfire posing an immediate threat.

In fact, the urgency is immediate. Building a life-long habit, not just whetting an appetite, takes time and repeated exposures to the arts. It also involves engaging older students, not just younger kids at summer camps.

Theaters must build “a continuum of care” that engages children at a young age, keeps them hooked in adolescence as they begin to determine how they will spend their own spare change, and finally cement a lifetime fascination with theater as a pastime as familiar to fledgling adults as Michael Bay blockbusters or X Box games.

It doesn’t help that arts education is being sliced due to funding shortfalls from Tallahassee. Once again, policymakers give paternalistic empty nods to pleas for the need for the arts in even a lop-sided education.

And yet, a huge number of youngsters in Gen ADD already have a demonstrable interest in theater to capitalize upon. Scores upon scores of high schools have drama programs, student productions or participation in the Cappies program. Two dozen schools have magnet programs; some charter schools are devoted to the arts attended by the future lawyers who will sit in the audience, donate money and volunteer for boards of directors. Palm Beach County alone has 22 high schools teaching 4,000 students in some type of drama/theater category. Broward has 12,000 children in theater classes in all grade levels. Should we even mention Glee? The Kravis Center in West Palm Beach has just announced the De George Academy to train “economically disadvantaged youth demonstrating a strong interest in the performing arts” from all grade levels.

The tragedy is that many of these “theater kids” are not exposed to professional theater productions more than once, if at all, when theaters should be dragging in these students over and over.

Some programs do exist to reach the non-theater students, funded primarily by outside foundations and donors with some tax funds involved, such as the Cultural Passport in Miami-Dade, GableStage taking productions directly into the schools as well as inviting students to the theater itself, Broward Center for the Performing Arts’ Teen Ambassador program, and Dramaworks picking up of the leadership to maintain Dreyfoos School of the Arts’ Emerging Artists Showcase. PlayGround Theatre has not only bused in tens of thousands of elementary school children but sent its staff to teach in schools.

What so many efforts lack is follow-up to build up a habit. When a student comes to see a rock n’ roll Hamlet at a theater, they ought to be offered right then a cut-rate admission to another program.

One avenue is to recruit students as interns like Slow Burn Theatre Company does with West Boca Community High School students or enlist the student bloggers and tweeters mentioned earlier to talk up an evolving production. They also offer free tickets to the high school’s students to be their beta testing audience at their run-through performances.

Of course, another key is to keep student prices down to what a teenager spends to go see the latest episode of the Twilight saga.

Someone Is On Our Side, No One is Alone: Cooperation

It only lasts about 90 seconds. Three-score actors, directors, crew and playwrights literally join hands for the curtain call at the end of the semi-annual 24-Hour Theatre Project fundraisers. For that one moment, the South Florida theater community actually becomes a community. But that cohesion for a common cause is a rarity, even when self-preservation is at stake.

It only lasts about 90 seconds. Three-score actors, directors, crew and playwrights literally join hands for the curtain call at the end of the semi-annual 24-Hour Theatre Project fundraisers. For that one moment, the South Florida theater community actually becomes a community. But that cohesion for a common cause is a rarity, even when self-preservation is at stake.

Nothing seems as suicidal as the competition-driven refusal of many theaters to join forces for both the aesthetic improvement and fiscal health of the art form. Everyone certainly gives lip service and many people make limited efforts costing them little or nothing. But as we explored in the previous essay, those laudable efforts are insufficient. Theaters are squandering a pragmatic lifeline that produces mutual benefits

This must change. The need goes far beyond actively and enthusiastically supporting the obvious rallying point of the South Florida Theatre League or the Florida Professional Theatres Association joint projects — which few do now. It lies in changing the secret mindset that says I cannot thrive if you do. Not every project will benefit every theater’s immediate bottom line. But an increasingly healthy theater scene has a long-term synergy for everyone: Instead of trying to get a bigger share of the pie, as we said, bake a bigger pie by building that public awareness and receptivity to Theater as a patron’s option.

The possibilities are limited only by imagination. Already, experiments and proposals are floating in the local ether. Ann Kelly, executive director of Mad Cat Theatre Company, has a pending request to the Knight Foundation to kickstart a cooperative scene shop where artists can collaboratively build sets, store props and share expensive tools. An enterprising soul could expand that to include costume and prop shops. Theaters with their own shops currently could benefit at a minimum from storage. This isn’t a fantasy; it occurs in other cities.

What if a half-dozen or even a score of theaters contributed a proportional share to a marketing fund that could produce the high profile advertising or survey research that is beyond everyone’s current budgets? Across the country, projects have succeeded in sharing everything from group health insurance to box office operations to bookkeeping. Of course, civilians would suggest sharing email and snail mail lists, but it’s more likely that Gov. Rick Scott will increase his arts appropriation first. How about even more centralized auditions, coordinating opening nights that don’t conflict with others’ fundraisers, organizing groups to speak at political budget hearings, on and on?

Sadly, leaders are skeptical because of failed attempts. Despite years of discussions, no one has succeeded in organizing a daily or even thrice-weekly theater directory display ad in the newspapers. That kind of listing in The New York Times creates a perpetual region-wide public awareness of theater as a place to spend money. While the local newspapers reportedly have not been receptive in the past, we’ll bet they’re desperate enough at this point to accept anything that brings in money. There’s a project for the Knight Foundation or the county grant agencies to consider subsidizing.

Co-productions are another avenue. The Maltz’s Barnum in 2009 was produced in association with the Asolo Repertory Theatre in Sarasota resulting in a lush production with a $400,000 budget, saving about 18 to 20 percent in additional costs. This coming season’s Singin’ In The Rain will be a partnership with the Fulton Theatre in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and its Thoroughly Modern Millie will move to the renowned Papermill Playhouse in New Jersey. Most encouraging has been the Arsht’s partnerships with Zoetic Stage, City Theatre, Mad Cat and now Alliance Theatre Lab. The Arsht, Broward Center and Kravis should expand these efforts.

The Miami Theater Center (the rebranded and expanded PlayGround Theatre in Miami Shores) envisions lending its Sandbox black box to companies along with a $500 stipend to groups wanting to take more time developing new works and new techniques.

Think wider. Almost all of these initiatives can be applied to the overall arts community as well. The efficiencies of scale, the brainstorming, the sharing of resources all become exponentially more effective when ballet, opera, visual arts, and classical music find areas where they can help each other. Nowhere is this more effective than lobbying the budget and policy-making politicians, not just on the county level but in Tallahassee.

As we noted, the infrastructure already exists with groups such as the South Florida Theatre League.

Politics and Poker: Government

It would be a waste of space here to ask governmental bodies for a dependable revenue stream like a bond issue or taxing district for parks and arts as they did in Salt Lake City. Why repeat the need for larger, more flexible grants? Why point out that Chicago and London have thriving theater scenes because local, regional and national governments subsidized it for decades, gaining a major tourism draw and a catalyst for economic downtown development from their investment. Why highlight the inexcusable shame that that Miami-Dade is the only one of the three county cultural agencies to donate money to the South Florida Theatre League? For Brutus is an honorable man.

What’s called for is for theaters to act like special interest lobbyists – something politicians understand. This must go far beyond giving free tickets to the mayor for opening night. It goes beyond showing up at a final county budget hearing that just rubber stamps what was decided months earlier. That’s all too little too late.

Professional theater corps in tandem with their partisans must pressure politicians who don’t believe there is a critical mass of constituents who care. The city of Chicago helped fund the creation of the Chicago Shakespeare Theater on the Navy Pier because the public made its support clear – publicly and privately, loudly and quietly, and above all, frequently.

A clear case study is Palm Beach Dramaworks where Managing Director Sue Ellen Beryl became deeply involved not just in lobbying governmental bodies like the Downtown Development Association, but becoming involved in committees. Dramaworks’ journey from one performing space to another to the current breathtaking facility has been facilitated by Beryl’s ongoing interaction with politicians and bureaucrats. Most artistic directors probably have no time to do this, but their board members do.

But even that’s not enough. Listen to this journalist who has covered government more than 40 years. A small vocal cadre of interested citizens can mold government action by speaking out at the same time. This rarely works during a huge controversy, but it does work many other times. Every email, every phone call, every written letter receives a mental multiplier of 10 or 20 in the politician’s office.

The real obstacle is overcoming the natural inertia, pessimism and downright laziness of artists and their supporters. Actors, designers, stage managers, crew members, audience members all should be taking five minutes to pen three-paragraph notes to their elected representatives. Artistic directors should insist every single member of their board of directors write such letters on their own business letterhead (not emails and not a form letter) to each politician in their city, county and statehouse asking for action. It should be a requirement for continuing service on the board. If only a dozen theaters out of the 40-plus professional theaters did that, politicians would notice. If those dozen theaters asked five of their major philanthropic donors to do the same, politicians would notice, especially if those donors are high-profile names in the community. If those dozen theaters asked their audiences to do the same and only 10 people out of their hundreds of patrons followed through, politicians would notice.

There’s A Place For Us: Space

Small and mid-sized companies need an affordable, accessible home. Unfortunately, most new spaces being built by counties and municipalities are too big and expensive for local theater companies.

One answer is the co-op multi-plex approach being experimented with in regional centers across the country. In this model, one or more small to mid-sized theaters operate three side-by-side fully-equipped flexibly-configured 75- to 99-seat spaces as semi-permanent bases. Some are just black boxes as they have at Theater Wit in Chicago. Some may add a modest proscenium theater such as a repurposed junior high school in Arlington, Virginia. The facility itself usually has an executive director for administration and scheduling. At the Broadway Center in Milwaukee, three permanent companies share bookkeeping, box office and other non-competitive operations. The Arlington facility has a co-op scene shop and costume shop that also earn revenue serving companies not performing there.

The idea is being toyed with locally but not with the necessary scope: Miami Light Project rents out its facility, but it has a single space available and is still working out the logistics. The vest-pocket Empire Stage in Fort Lauderdale is doing that too, but it barely has 55 seats. Barry University’s Pelican Theater has also been loaned out for free to four companies such as Naked Stage, Alliance Theatre Lab, Blue Dog and The Project.

Long term, the region needs at least one more major theater to provide more work, to subsidize local talent working at smaller companies and to increase our local and national profile. Any realization is years off, at best, for something like the resurrection of the Coconut Grove Playhouse. If it happens, it likely will not be a new entity, but the evolution of an existing company occupying a new high-profile facility.

A tent-pole could be the anchor for the other long-term need, a theater district. Obviously, this will never be as expansive as The Loop. But the city fathers of Coral Gables, which passed on this once before, could fill some of its empty storefronts with small companies needing government-subsidized space. The only good thing about the poor economy is that options are everywhere such as the empty Fashion Mall in Plantation.

Both ideas seem unlikely to coalesce in the near future. But the items need to be part of the region’s strategic plan and even secreted in the file folders of a company or two.

I Want To Be A Producer: Boards of Directors

Dear boards of directors: Get off your butts. Some of you are generous, hard-working and dedicated altruists. Others of you are deadwood soaking up the status of being an arts patron because you wrote a check and donated something to an auction for a tax write-off.

A check isn’t enough. Even assigning an accountant or junior lawyer in your firm to provide in-kind services is not enough. This is a checks-and-balances job, a crucial responsibility that determines the ongoing survival of an arts company and the health of our cultural landscape. If all you want is the glory, ask the boards of Florida Stage, Caldwell and Coconut Grove Playhouse how their personal reputations fared when those ships sank on their watch.

First, get engaged. Read the financial reports, apply your years of expertise to spot fiscal shoals ahead and possible efficiencies. If you don’t have the expertise, many government, arts and business groups offer seminars in the craft. More on that later.

Second, develop a collegial, supportive but watchdog relationship with the artistic director and managing director. You shouldn’t micro-manage artistic and creative judgment calls. But when the artistic director wants to buy a real mink coat for a costume (this actually happened years ago) it’s your job to yank on the reins. When administrative and even artistic policies seem destructive, such as a sharp 90 degree change in programming, you need to at least ask questions.

Being a lapdog does the theater no good. You know you’re doing it right if your leadership is strong enough that the theater will survive the death or departure of the founding artist. That’s the hallmark of an institution rather than a company. It doesn’t have to be, nor should it be combative. Boards need to courageously support their artistic and creative staff taking risks and growing the theater. When you believe in what you and your artistic directors want to do, you have to remain loyal even when facing choppy economic seas.

Finally, get your hands dirty and make the theater an inescapable piece of the community landscape. Talk it up at the country club. Hand out flyers. Address civic clubs. Write newspapers editor that you want more coverage. Write politicians that the arts need more funding. Court potential donors. Serve as the theater’s envoy on community committees. Get out there.

Art Isn’t Easy: Funding

One interviewee said that money won’t solve all the problems. No, but it sure would (a) increase marketing and thereby audiences (b) improve the talent pool by providing a living wage (c) provide a stable home base to perform from. God bless Adrienne Arsht and the Carnival folks for underwriting the downtown Miami facility, but imagine what Mad Cat, GableStage, New Theatre, Actors Playhouse, Alliance Theatre Lab, Ground Up & Rising, not to mention community, children’s and university theaters in Miami-Dade could have done with a share of Ms. Arsht’s $30 million?

Clearly, the relatively modest funds that government is providing (Canadians would laugh at the figures) is no longer dependable, already sliced by about a third. An admirable long-term goal would be government providing a dedicated funding source like a bond issue that could not be cut and would allow theaters to have a reliable bedrock budgeting figure. Some day.

So it’s up to the theater community to follow the money. The usual suspects are claiming to be tapped out. Instead, focus efforts on new fresh targets. The money is in the deep pockets of philanthropists, corporations and relocating international businesses. Add targets by moving your crosshairs to smaller companies as well, not just the mega-corporations. Few theaters have hit them up and they may simply need to be courted. Like independent book store owners hawking their wares, theater has to be hand sold to patrons and donors with the kind of personal attention that Dramaworks and the Maltz invest. If the staff is too small or overloaded to do that, then members of the board should take up the task, especially inviting appropriate people to join the board.

Unfortunately, donors usually want naming rights to something concrete like the stage or the bathroom mirrors. But what is obviously needed far more desperately is operational and marketing dollars. That’s why bringing in patrons to watch rehearsals and making them “producers” of a particular show is a smart move. The ultimate financial goal at this juncture is to attract endowments for operating expenses rather than seeking contributions toward bricks and mortar.

There are also “new” retirees from upper middle- income families now looking for somewhere to invest their income. Case in point: Actors Playhouse recently mounted Becky’s New Car, a play commissioned by Seattle real estate broker Charles Staadecker as a present for his wife’s 60th birthday. Since then, Charles and Benita have helped match patrons to playwrights and their efforts have led to 19 commissions. They are banding with friends to split up the estimated $25,000 cost of commissioning another new play themselves. Sharing the burden costs each backer about $3,000 a year for two years or $250 a month – less than the cost of leasing a car, he said.

How To Succeed in Business Without…

There’s not much fun in taking care of business, but more artistic directors are wisely paying more attention to the balance sheet. Mosaic’s Executive/Artistic Director Richard Jay Simon has been hiring freelance directors for some shows to enable him to spend more time ensuring Mosaic’s fiscal future. In fact, theater administrators need to invest more time in training staff members with an eye for taking over years from now – or just during vacation.

The key business facet that needs more attention is strategic business planning. As we advised in the last piece, the board and the administrators have to figure out what its priorities are five years down the line so it knows where to invest its limited resources today. What changes do they want to make? What happens if they lose their current space? What do they do if a hurricane knocks out one production? What happens if the artistic director gets hired away by another company?

There’s a lot of help out there for administrators and board members who want to learn those skills. For instance, the Arts & Business Council of Miami has a variety of programs and is introducing a new one next month to help recruit and match board members to cultural groups. Miami-Dade County with the support from the Knight Foundation has worked with 60 individuals and groups through the Kennedy Center’s de Vos Institute over the last 18 months. The National Arts Strategies will hold a Strategic Governance workshop in Miami in November. Informal advice is also available with a phone call to Theater Communications Group or a cultural council or another arts group in a different discipline, even to a competitor. What is required is having the courage to ask for help when you’re drowning or admitting you need to learn more.

Sometimes good business is doing things differently and the trick is keeping aware how other original thinkers are changing business as usual. For instance, some of the most creative thinking recently has been aimed at staunching the loss of subscriptions by offering the utmost in flexibility to subscribers. Dramaworks allows subscribers in one configuration to take any five of the six shows in a season. Mosaic allows subscribers to choose different dates for different shows as late as a week ahead of time. Theater Wit in Chicago, which houses three small companies, offers its patrons a monthly subscription of $29 for which a patron can see all three shows at any time space is available – and come back as often as they like during the month, space permitting.

Please, Sir, May I Have Some More: Demanding Improvement

Publicly, at least, people who love theater on both sides of the footlights are rarely anything but laudatory about everything and everyone. (Not so true in private; they’ll rabidly disagree about whether any specific show was praiseworthy or execrable). Some of this results from the us-against-the-Phillistines trench mentality of the embattled community of audience and creative souls.

But it’s not doing anyone any favors. The level of achievement and quality will never improve if we keep patting each other on the back, especially when the work is just mundane“okay.” That goes for actors, director, audience members and critics, including this one.

Directors need to demand their actors dig deeper in themselves and not rely on the same performance; artistic directors need to ask local playwrights for one more rewrite of a new script; audiences need to stop fawning over playwrights at readings and instead deliver the constructive criticism the author really needs; audiences and critics should stop giving standing ovations and raves to mediocre work.

This isn’t being disloyal; it’s urging people we care about to reach higher and not settle.

Finishing The Hat: Coda

Several interviewees used the same phrase to defend their persistent hopefulness despite the lengthy list of challenges and daunting nature of the solutions. They said professional theater in South Florida, more than any other art form, is a young one, not even two generations old. It has a lot to learn but it has a young community’s capacity to learn and grow and thrive.

It’s not Pollyanna optimism. As we said repeatedly from the very beginning, South Florida’s artists and audiences have proven over and over that they do not just survive, they prevail armed with little more than sheer vision, imagination and drive. More than anything else, South Florida theater partisans must take inspiration from how far it’s come already, to strengthen the resolve that it can go even farther.

If things sometimes seem desperate, there’s a benefit there. Playwright Lorraine Hansberry wrote in The Sign In Sidney Brustein’s Window: “Desperation is energy, and energy can move things.”

One actor said in an interview, “We’re running on fumes.” A few days later, an experienced arts administrator unaware of the actor’s remark, said. “The arts community down here will run on fumes of encouragement.”

Consider yourself encouraged.

— — — —

Click here to read Monday’s essay — On the Wheels of a Dream: South Florida Theater: What It Is And What It Can Be

Click here to read Wednesday’s essay — Ya Got Trouble Right Here in River City: The Challenges

Acknowledgments

The opinions here are mine except where noted, but they were informed and synthesized from ideas generously shared by many people over the past two years.

Among those who spent 1 ½ to 2 hours speaking for this article this summer, we thank Joe Adler, producing artistic director and co-founder of GableStage; Antonio Amadeo, actor, director and co-founder of Naked Stage; Stephanie Ansin, artistic director of Miami Theatre Center; Andie Arthur, executive director of the South Florida Theater League; Nan Barnett, consultant and former managing director of Florida Stage; Mary Becht, former director of the Broward County Cultural Division; Sue Ellen Beryl, managing director of Palm Beach Dramaworks; Rena Blades, CEO of Palm Beach Cultural Council; Linnea Brown, director of public relations, Maltz Jupiter Theatre; Anne Chamberlain, actress; Mark Della Ventura, actor and playwright; Christopher Demos-Brown, playwright and co-founder of Zoetic Stage; Todd Allen Durkin, actor; Arturo Fernandez, actor and co-founder of Ground Up and Rising; William Hayes, producing artistic director of Palm Beach Dramaworks; Andrew Kato, producing artistic director of Maltz Jupiter Theatre; Ann Kelly, executive director/business manager of Mad Cat Theater; Margaret M. Ledford, president of the South Florida Theatre League; Amy London, director, stage manager, actress, producer and executive director of the Carbonell Awards; Robin Reiter-Faragalli, philanthropy consultant and arts advocate; Kelley Shanley, president and CEO of the Broward Center for the Performing Arts; Deborah Sherman, actress and co-founder of The Promethean Theatre; Scott Shiller, executive vice president of the Adrienne Arsht Center for the Performing Arts; Richard Jay Simon, executive/artistic director of Mosaic Theatre; David Sirois, actor and playwright; Michael Spring, director of Miami-Dade County Department of Cultural Affairs; Barbara Stein, executive producing director of Actors Playhouse; Louis Tyrrell, former artistic director of Florida Stage and current artistic director of the Theatre at Arts Garage, and Savannah Whaley of Pierson Grant Public Relations.

During the past two years, we’ve also had informal and email conversations about these topics with scores of people including Derelle Bunn, executive producer/artistic director of Broward Stage Door; publicist Charlie Cinnamon; Matthew Korinko, co-artistic director, Slow Burn Theatre Compsny; Rebekah Lanae Lengel, managing producer of Miami Light Project; John Manzelli, co-founder Naked Stage and artistic director of City Theatre; Michael Peyton, director of corporate sponsorship and underwriting for WLRN; Jennifer Sardone-Shiner, director of marketing at the Maltz; Larry Stein, president of Actors Playhouse; Paul Tei, co-founder of Mad Cat Theatre Company; Tricia Trimble, managing director of the Maltz; and many members of the Carbonell judging panel and the American Theatre Critics Association.

We also have conferred about the issues and gathered data with artistic and managing directors and other staffers at Actors Equity Association; Actors Theatre of Louisville; Arena Stage in Washington, D.C.; Chicago Theatre League; Broadway Theatre Center comprising Skylight Opera Theatre, Milwaukee Chamber Theatre and Renaissance Theaterworks; Steppenwolf Theater Company; Chicago Shakespeare Company; Milwaukee Repertory Theater; Goodman Theater; Lookinglass Theatre (Chicago); Theater Wit and Stage 773 (Chicago); Black Ensemble Cultural Center (Chicago), DC place; Oregon Shakespeare Festival; Stratford Shakespeare Festival, and the Shaw Festival in Niagara-on-the-Lake.

We looked at IRS 990 tax returns as well as grant records for many companies with the help from Adriana Perez of the Miami-Dade County Department of Cultural Affairs, James Shermer of the Broward County Cultural Division and Jan Rodusky of the Palm Beach Cultural Council.

Once again, our thanks.

And Make Our Garden Grow: Finding The Solutions

Who are we? Where do we want to go? What’s standing in our way? How do we prevail? The dwindling days before the season gears up are a prime time for us all, audiences to artists, to invest in a tough self-examination of South Florida theater.

We suggest concrete answers in three extensive essays this week. The opinions are ours, but they result from more than 30 lengthy interviews and dozens of shorter ones with professionals in the region and across the country who we will list at the end of each article. In the first part on Monday (click here), we defined precisely what South Florida theater is and can be. The second on Wednesday (click here) dissected the handicaps, shortcomings and challenges. The last and longest essay today offers potential solutions.

It’s unlikely you’ll agree with half of what is suggested. Some observations will seem obvious. Some may even be wrong. Some may get you angry. Good. We’re throwing chum in the water to start an overdue conversation in lobbies, dressing rooms, board rooms and cyberspace. Talk back to us. We want your signed responses in the comments sections at the end of the articles, or in your own essays that we will consider editing and publishing if you send them to bill@floridatheateronstage.com.

By Bill Hirschman

In the film Shakespeare In Love, the producer says theater’s “natural condition is one of insurmountable obstacles on the road to imminent disaster… Strangely enough, it all turns out well.” When asked how, he says, “I don’t know. It’s a mystery.”

It’s a delightful scene. And it’s wrong.

We may not know all the answers, but we know some of them. We’re trying some even now.

Best of all, we are armed with one inestimable weapon: passion. Don’t scoff. That’s not a saccharine homily from a Disney musical. You didn’t see the fervor that suffused nearly every interview we had with actors, designers, directors, administrators and supporters. Some of the joy was mixed with anger and an unspoken feeling of betrayal; some of the hopefulness was tempered by disappointment and fear. But the gleam in the eyes and the power in the voices of such disparate partisans as Arturo Fernandez of Ground Up & Rising and Scott Shiller of the Arsht Center evidenced an energy, idealism and belief in the worth of art.

What came clear from months of study and thought was the need for – and the likely success of — audiences and artists dredging up the sheer will to escalate their investment.

Of course, there is no one-size-fits-all solution or even series of solutions. Some of the problems facing the Maltz Jupiter Theatre are different than those facing Actors Playhouse in Coral Gables, although they both mount large-scale musicals. The course is for each county, each community, each company to pull what works best for them from the menu of options that we’re about to explore.

I’m Still Here: Awareness

Theater must engage.

In the last essay, we hammered that an immediate priority must be injecting theater into the consciousness of the general public, the budget-controlling policymakers, the philanthropists, a younger audience and tourists. The crucial task is to build the hunger for theater in our communities, even a sense of entitlement that theater is part of the cultural fabric.

That, of course, means marketing, and while marketing usually means money that many troupes don’t have, some of the solutions primarily require inventiveness, elbow grease and resolve.

It takes money to buy billboards, but it doesn’t cost anything for the chairman of the board to speak at a Chamber of Commerce luncheon about how theater is an economic driver in the community. It requires little to enlist 20 high school drama students to audit design meetings, set construction and rehearsals to create a cadre of bloggers who will spread word of a show far beyond an old email list of Baby Boomers.

Obviously, the Internet has become an attractive tool, primarily because it’s free other than the internal staff time. But it needs to be used more inventively.

Theaters need to pick up on best practices discovered by other regional theaters such as the Denver Center for the Performing Arts. It’s not just sending emails and posting on Facebook or Twitter. It’s the interactive multi-media videos, contests and other ploys that attract people. Some companies like the Maltz have aggressively explored options like putting up buzz-building micro-sites – pages with backstory and behind-the-scene videos for each production to intensify audience interest.

Several local theaters are experimenting with videos that can go virally, but most are pretty dull. In contrast, check out Slow Burn Theatre Company’s promotional video by clicking here. (http://www.facebook.com/photo.php?v=10150895582561846) Additionally, Google Analytics provides several levels of drill-down information about who is visiting your website, providing free clues to your audience’s demographics and whether certain promotions are gaining traction.

Some theaters with predominantly older audiences only half-heartedly use the Internet, believing their patrons aren’t online. Horse puckey. See how many seniors are scrolling through their emails and checking out web sites on their smartphones while waiting for the house lights to go down.

But Internet marketing shares the same limitation as brochures sent to a snail mail list: It’s preaching to the choir. While advertising gurus say repeated contacts translate into future sales, theaters need to discover how to market on the cheap to the people who are not already in contact with the theater.

For instance, Florida has a rich built-in market that is rarely tapped: tourists. In Chicago, roughly a fifth of the five million tickets are sold to tourists and conventioneers each year. Even without a beach as a draw, tourists flock annually to the Stratford Shakespeare Festival in the-middle-of-nowhere Canada or the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in remote Ashland just to see theater.

The Arsht and the Broward Center for the Performing Arts have experimented with outreach to the tourists. But redoubled efforts are needed to put already-printed lobby cards and mailers in the attraction racks in hotel lobbies. Concierges should suggest theater as part of a dinner package for sun-burned visitors stymied by the evening rainstorms. Hotel managers should mention theater in guests’ welcome materials or to packets sent to convention planners.

I’m Reviewing the Situation: A Few More Ideas

An abbreviated list would also include:

* Mass Media: Many theaters have given up too easily trying to get better media coverage, especially from television. They’ve been rebuffed by editors because their story ideas would bore anyone except insiders. But overtaxed journalists love it when a story that is interesting to a general audience is laid in their lap. Just be certain it has visual elements that can be filmed or photographed. Want to pitch August: Osage County? It’s not a three-hour Pulitzer Prize winner lauded for its insights and language; it’s a slugfest of family dysfunction that makes the Real Housewives look like lightweights. That can be illustrated with a couple of choice clips from rehearsals. But theater staffs must make direct contact with TV news directors and print section editors (even occasional face to face contact) with specific and unique story ideas that they would actually like to watch themselves.

* Niche marketing: Some theaters are marketing the merits of a particular show rather than the company itself as brand. Take a clue from Tyler Perry. For decades, Perry’s theater comedies geared to black audiences were marketed through African American churches. Spend the limited marketing dollars targeting promising audiences. For Death and Harry Houdini, the Arsht partnered with the local Brotherhood of Magicians. When the Maltz does Amadeus this year, it would make sense to hook up a promotion with a classical music radio station.

* Promote the actors as a brand: Currently, some advertising does not mention the actors or director. But just like film audiences, some regular patrons will go see a show simply because they’re admirers of the work of Todd Allen Durkin or Angie Radosh or J. Barry Lewis.

* Carbonell Awards: A tug of war has ensued for years between insiders wanting to keep Theater Prom as an insular intimate industry party and those who want it to be a high-profile public blowout. But clearly, the Helen Hayes, the Jeffersons and the Tony Awards have increased Theater’s visibility in the general populace’s cognition. Those programs get atypical media coverage, even on television. Fans in those communities, not just theater workers, look forward to attending the ceremonies. The primary roadblocks are the cost and logistics of marketing the ceremony and adding headliners who will attract a larger audience, a facet that insiders have openly resented in the past.

Come To The Cabaret: Advanced Marketing

One major initiative is being explored by tourism officials and the Broward Center for the Performing Arts — creating a major cultural event that will draw people from around the country and even around the world, like Miami Beach’s Art Basel. Whether or not this is a theater-centric event, it can be designed with theater built directly into its weave. Again, we have international name recognition already. Who even knows where Ashland is?

More achievable in the short run is “Event Marketing,” which targets Millennial and Boomer audiences accustomed to spending an entire evening out. Theaters are trying to engage their potential audiences by making the play one part of a packaged evening with stops before and/or after the theater. This is more structured and elaborate than the current practice of simply providing a discount at a nearby restaurant by showing a ticket stub (hours after dinner is over, we might add). Actors Playhouse combined Real Men Sing Show Tunes with a pub crawl. Mosaic Theatre encouraged tailgate parties before Lombardi as well as talkbacks with noted sports figures rather than just the actors.

A subset of “The Event” is “The Buy-In.” It narrows the gulf between audience and the art by allowing them to witness the process of their theater being made. In the past, this has been restricted to staged readings. But that is changing. The new Outré Theater Company in Boca Raton is planning to sell a ticket that would provide patrons access to selected planning meetings and rehearsals. The Maltz rewards its Circle of Friends donors with a meal and a field trip to tour the costume shop or watch the carpenters at work or interact with the visiting artists, anything to increase their emotional investment in the show. Seeing that sound effects and lighting don’t just appear magically, but result from hard work makes them feel part of the creative process.

What’s Playing At The Roxy?: 21st Century Programming

Watching the Goodman Theatre’s transcendent production of O’Neill’s epic The Iceman Cometh this summer in Chicago, one thought persisted through the 4 ½-hours, four acts with three intermissions: Mamet could have done it in half the time. Not as well. Not delivering the profound depths of elegiac tragedy. But a lot more economically.

Storytelling has changed since the days of Ned the Neanderthal, since Aristophanes and since O’Neill. While 21st Century theater absolutely must present those archetypal plays intact, modern theater must embrace that narrative is evolving and splintering into different paradigms.

It’s not contradictory that, at the exact same time, theater must emphasize its millennia-old strengths that no other medium can duplicate –experiential, immersive theatricality in tandem with the immediate connection of being in the same room with a live storyteller with a congregation of other people.

Building audiences not eligible for their AARP card requires leaning more heavily on visual, stylized theater. It needs to speak to a more attention-challenged audience that already knows storytelling shorthand from decades of watching movies. It needs to indulge in affordable theatrical spectacle that relies on imagination more than cinematic explosions such as Naked Stage’s bare bones The Turn of the Screw this summer in Miami.

The Arsht management obviously buys into stylized theatricality. This season it will import its third annual visit from the House Theatre of Chicago. The Sparrow in 2011 made it clear that some audiences hungered for such fare. Death and Harry Houdini this April sold out most performances. And finally, like it or not, the Arsht may be blurring the definition of theater with its spectacle-driven Fuerza Bruta and The Donkey Show, but it’s also bringing in an audience beyond balding greybeards. The as-yet unanswered question is whether any of those disco dancers can be enticed to see the Arsht’s hosting of Zoetic Stage’s production of I Am My Own Wife this fall.

The sea change in programming needs to be eased into, but evolution is possible. Producing Artistic Director Joe Adler said that while GableStage has sought thought-provoking theater, his audience would not have stood for the profane and funny The Motherf**ker With The Hat ten years ago. Similarly, Artistic Director David Arisco has nudged Actors Playhouse audiences in Coral Gables. While 2003’s Floyd Collins was as disastrous commercially as it was an artistic triumph, Arisco has trained his doggedly mainstream audience to accept the marathon of unsettling August: Osage County and the musical Next To Normal about a family coping with bipolar disorder and electroshock therapy. Those shows succeeded, producer Barbara Stein surmises, because they were the titles that Floridians had heard about, but hadn’t seen in New York or the shows never toured here. It’s making the same bet with Other Desert Cities this spring.

As challenging and risk-taking as theater has to be to engage new audiences, consistency of quality is what keeps bringing people back. Until its meltdown last year, Florida Stage audiences returned season after season to a slate of world premieres that they knew nothing about. But they were certain that even a near-miss of a play in development would be a well-made, intriguing work. GableStage could produce Sarah Kane’s raw and rugged Blasted in 2010 because the company’s audience trusted the company’s reliability.

And while no one wants thought-provoking theater more than theater critics, there’s still a palatable need in these trying times for sheer entertainment, even mindless fun.

Children Will Listen: Growing The Next Audience

It’s old news that survival into another decade relies on growing the next audience. But while almost every major theater has a youth-oriented program, the crucial drive to engage and seduce tomorrow’s patrons sometimes gets short shrift because many theater leaders don’t perceive the need as a grassfire posing an immediate threat.

In fact, the urgency is immediate. Building a life-long habit, not just whetting an appetite, takes time and repeated exposures to the arts. It also involves engaging older students, not just younger kids at summer camps.

Theaters must build “a continuum of care” that engages children at a young age, keeps them hooked in adolescence as they begin to determine how they will spend their own spare change, and finally cement a lifetime fascination with theater as a pastime as familiar to fledgling adults as Michael Bay blockbusters or X Box games.

It doesn’t help that arts education is being sliced due to funding shortfalls from Tallahassee. Once again, policymakers give paternalistic empty nods to pleas for the need for the arts in even a lop-sided education.

And yet, a huge number of youngsters in Gen ADD already have a demonstrable interest in theater to capitalize upon. Scores upon scores of high schools have drama programs, student productions or participation in the Cappies program. Two dozen schools have magnet programs; some charter schools are devoted to the arts attended by the future lawyers who will sit in the audience, donate money and volunteer for boards of directors. Palm Beach County alone has 22 high schools teaching 4,000 students in some type of drama/theater category. Broward has 12,000 children in theater classes in all grade levels. Should we even mention Glee? The Kravis Center in West Palm Beach has just announced the De George Academy to train “economically disadvantaged youth demonstrating a strong interest in the performing arts” from all grade levels.

The tragedy is that many of these “theater kids” are not exposed to professional theater productions more than once, if at all, when theaters should be dragging in these students over and over.

Some programs do exist to reach the non-theater students, funded primarily by outside foundations and donors with some tax funds involved, such as the Cultural Passport in Miami-Dade, GableStage taking productions directly into the schools as well as inviting students to the theater itself, Broward Center for the Performing Arts’ Teen Ambassador program, and Dramaworks picking up of the leadership to maintain Dreyfoos School of the Arts’ Emerging Artists Showcase. PlayGround Theatre has not only bused in tens of thousands of elementary school children but sent its staff to teach in schools.

What so many efforts lack is follow-up to build up a habit. When a student comes to see a rock n’ roll Hamlet at a theater, they ought to be offered right then a cut-rate admission to another program.

One avenue is to recruit students as interns like Slow Burn Theatre Company does with West Boca Community High School students or enlist the student bloggers and tweeters mentioned earlier to talk up an evolving production. They also offer free tickets to the high school’s students to be their beta testing audience at their run-through performances.

Of course, another key is to keep student prices down to what a teenager spends to go see the latest episode of the Twilight saga.

Someone Is On Our Side, No One is Alone: Cooperation

It only lasts about 90 seconds. Three-score actors, directors, crew and playwrights literally join hands for the curtain call at the end of the semi-annual 24-Hour Theatre Project fundraisers. For that one moment, the South Florida theater community actually becomes a community. But that cohesion for a common cause is a rarity, even when self-preservation is at stake.

It only lasts about 90 seconds. Three-score actors, directors, crew and playwrights literally join hands for the curtain call at the end of the semi-annual 24-Hour Theatre Project fundraisers. For that one moment, the South Florida theater community actually becomes a community. But that cohesion for a common cause is a rarity, even when self-preservation is at stake.

Nothing seems as suicidal as the competition-driven refusal of many theaters to join forces for both the aesthetic improvement and fiscal health of the art form. Everyone certainly gives lip service and many people make limited efforts costing them little or nothing. But as we explored in the previous essay, those laudable efforts are insufficient. Theaters are squandering a pragmatic lifeline that produces mutual benefits

This must change. The need goes far beyond actively and enthusiastically supporting the obvious rallying point of the South Florida Theatre League or the Florida Professional Theatres Association joint projects — which few do now. It lies in changing the secret mindset that says I cannot thrive if you do. Not every project will benefit every theater’s immediate bottom line. But an increasingly healthy theater scene has a long-term synergy for everyone: Instead of trying to get a bigger share of the pie, as we said, bake a bigger pie by building that public awareness and receptivity to Theater as a patron’s option.

The possibilities are limited only by imagination. Already, experiments and proposals are floating in the local ether. Ann Kelly, executive director of Mad Cat Theatre Company, has a pending request to the Knight Foundation to kickstart a cooperative scene shop where artists can collaboratively build sets, store props and share expensive tools. An enterprising soul could expand that to include costume and prop shops. Theaters with their own shops currently could benefit at a minimum from storage. This isn’t a fantasy; it occurs in other cities.

What if a half-dozen or even a score of theaters contributed a proportional share to a marketing fund that could produce the high profile advertising or survey research that is beyond everyone’s current budgets? Across the country, projects have succeeded in sharing everything from group health insurance to box office operations to bookkeeping. Of course, civilians would suggest sharing email and snail mail lists, but it’s more likely that Gov. Rick Scott will increase his arts appropriation first. How about even more centralized auditions, coordinating opening nights that don’t conflict with others’ fundraisers, organizing groups to speak at political budget hearings, on and on?

Sadly, leaders are skeptical because of failed attempts. Despite years of discussions, no one has succeeded in organizing a daily or even thrice-weekly theater directory display ad in the newspapers. That kind of listing in The New York Times creates a perpetual region-wide public awareness of theater as a place to spend money. While the local newspapers reportedly have not been receptive in the past, we’ll bet they’re desperate enough at this point to accept anything that brings in money. There’s a project for the Knight Foundation or the county grant agencies to consider subsidizing.

Co-productions are another avenue. The Maltz’s Barnum in 2009 was produced in association with the Asolo Repertory Theatre in Sarasota resulting in a lush production with a $400,000 budget, saving about 18 to 20 percent in additional costs. This coming season’s Singin’ In The Rain will be a partnership with the Fulton Theatre in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and its Thoroughly Modern Millie will move to the renowned Papermill Playhouse in New Jersey. Most encouraging has been the Arsht’s partnerships with Zoetic Stage, City Theatre, Mad Cat and now Alliance Theatre Lab. The Arsht, Broward Center and Kravis should expand these efforts.

The Miami Theater Center (the rebranded and expanded PlayGround Theatre in Miami Shores) envisions lending its Sandbox black box to companies along with a $500 stipend to groups wanting to take more time developing new works and new techniques.

Think wider. Almost all of these initiatives can be applied to the overall arts community as well. The efficiencies of scale, the brainstorming, the sharing of resources all become exponentially more effective when ballet, opera, visual arts, and classical music find areas where they can help each other. Nowhere is this more effective than lobbying the budget and policy-making politicians, not just on the county level but in Tallahassee.

As we noted, the infrastructure already exists with groups such as the South Florida Theatre League.

Politics and Poker: Government

It would be a waste of space here to ask governmental bodies for a dependable revenue stream like a bond issue or taxing district for parks and arts as they did in Salt Lake City. Why repeat the need for larger, more flexible grants? Why point out that Chicago and London have thriving theater scenes because local, regional and national governments subsidized it for decades, gaining a major tourism draw and a catalyst for economic downtown development from their investment. Why highlight the inexcusable shame that that Miami-Dade is the only one of the three county cultural agencies to donate money to the South Florida Theatre League? For Brutus is an honorable man.

What’s called for is for theaters to act like special interest lobbyists – something politicians understand. This must go far beyond giving free tickets to the mayor for opening night. It goes beyond showing up at a final county budget hearing that just rubber stamps what was decided months earlier. That’s all too little too late.

Professional theater corps in tandem with their partisans must pressure politicians who don’t believe there is a critical mass of constituents who care. The city of Chicago helped fund the creation of the Chicago Shakespeare Theater on the Navy Pier because the public made its support clear – publicly and privately, loudly and quietly, and above all, frequently.

A clear case study is Palm Beach Dramaworks where Managing Director Sue Ellen Beryl became deeply involved not just in lobbying governmental bodies like the Downtown Development Association, but becoming involved in committees. Dramaworks’ journey from one performing space to another to the current breathtaking facility has been facilitated by Beryl’s ongoing interaction with politicians and bureaucrats. Most artistic directors probably have no time to do this, but their board members do.

But even that’s not enough. Listen to this journalist who has covered government more than 40 years. A small vocal cadre of interested citizens can mold government action by speaking out at the same time. This rarely works during a huge controversy, but it does work many other times. Every email, every phone call, every written letter receives a mental multiplier of 10 or 20 in the politician’s office.

The real obstacle is overcoming the natural inertia, pessimism and downright laziness of artists and their supporters. Actors, designers, stage managers, crew members, audience members all should be taking five minutes to pen three-paragraph notes to their elected representatives. Artistic directors should insist every single member of their board of directors write such letters on their own business letterhead (not emails and not a form letter) to each politician in their city, county and statehouse asking for action. It should be a requirement for continuing service on the board. If only a dozen theaters out of the 40-plus professional theaters did that, politicians would notice. If those dozen theaters asked five of their major philanthropic donors to do the same, politicians would notice, especially if those donors are high-profile names in the community. If those dozen theaters asked their audiences to do the same and only 10 people out of their hundreds of patrons followed through, politicians would notice.

There’s A Place For Us: Space

Small and mid-sized companies need an affordable, accessible home. Unfortunately, most new spaces being built by counties and municipalities are too big and expensive for local theater companies.

One answer is the co-op multi-plex approach being experimented with in regional centers across the country. In this model, one or more small to mid-sized theaters operate three side-by-side fully-equipped flexibly-configured 75- to 99-seat spaces as semi-permanent bases. Some are just black boxes as they have at Theater Wit in Chicago. Some may add a modest proscenium theater such as a repurposed junior high school in Arlington, Virginia. The facility itself usually has an executive director for administration and scheduling. At the Broadway Center in Milwaukee, three permanent companies share bookkeeping, box office and other non-competitive operations. The Arlington facility has a co-op scene shop and costume shop that also earn revenue serving companies not performing there.

The idea is being toyed with locally but not with the necessary scope: Miami Light Project rents out its facility, but it has a single space available and is still working out the logistics. The vest-pocket Empire Stage in Fort Lauderdale is doing that too, but it barely has 55 seats. Barry University’s Pelican Theater has also been loaned out for free to four companies such as Naked Stage, Alliance Theatre Lab, Blue Dog and The Project.

Long term, the region needs at least one more major theater to provide more work, to subsidize local talent working at smaller companies and to increase our local and national profile. Any realization is years off, at best, for something like the resurrection of the Coconut Grove Playhouse. If it happens, it likely will not be a new entity, but the evolution of an existing company occupying a new high-profile facility.

A tent-pole could be the anchor for the other long-term need, a theater district. Obviously, this will never be as expansive as The Loop. But the city fathers of Coral Gables, which passed on this once before, could fill some of its empty storefronts with small companies needing government-subsidized space. The only good thing about the poor economy is that options are everywhere such as the empty Fashion Mall in Plantation.

Both ideas seem unlikely to coalesce in the near future. But the items need to be part of the region’s strategic plan and even secreted in the file folders of a company or two.

I Want To Be A Producer: Boards of Directors

Dear boards of directors: Get off your butts. Some of you are generous, hard-working and dedicated altruists. Others of you are deadwood soaking up the status of being an arts patron because you wrote a check and donated something to an auction for a tax write-off.

A check isn’t enough. Even assigning an accountant or junior lawyer in your firm to provide in-kind services is not enough. This is a checks-and-balances job, a crucial responsibility that determines the ongoing survival of an arts company and the health of our cultural landscape. If all you want is the glory, ask the boards of Florida Stage, Caldwell and Coconut Grove Playhouse how their personal reputations fared when those ships sank on their watch.

First, get engaged. Read the financial reports, apply your years of expertise to spot fiscal shoals ahead and possible efficiencies. If you don’t have the expertise, many government, arts and business groups offer seminars in the craft. More on that later.

Second, develop a collegial, supportive but watchdog relationship with the artistic director and managing director. You shouldn’t micro-manage artistic and creative judgment calls. But when the artistic director wants to buy a real mink coat for a costume (this actually happened years ago) it’s your job to yank on the reins. When administrative and even artistic policies seem destructive, such as a sharp 90 degree change in programming, you need to at least ask questions.

Being a lapdog does the theater no good. You know you’re doing it right if your leadership is strong enough that the theater will survive the death or departure of the founding artist. That’s the hallmark of an institution rather than a company. It doesn’t have to be, nor should it be combative. Boards need to courageously support their artistic and creative staff taking risks and growing the theater. When you believe in what you and your artistic directors want to do, you have to remain loyal even when facing choppy economic seas.

Finally, get your hands dirty and make the theater an inescapable piece of the community landscape. Talk it up at the country club. Hand out flyers. Address civic clubs. Write newspapers editor that you want more coverage. Write politicians that the arts need more funding. Court potential donors. Serve as the theater’s envoy on community committees. Get out there.

Art Isn’t Easy: Funding

One interviewee said that money won’t solve all the problems. No, but it sure would (a) increase marketing and thereby audiences (b) improve the talent pool by providing a living wage (c) provide a stable home base to perform from. God bless Adrienne Arsht and the Carnival folks for underwriting the downtown Miami facility, but imagine what Mad Cat, GableStage, New Theatre, Actors Playhouse, Alliance Theatre Lab, Ground Up & Rising, not to mention community, children’s and university theaters in Miami-Dade could have done with a share of Ms. Arsht’s $30 million?

Clearly, the relatively modest funds that government is providing (Canadians would laugh at the figures) is no longer dependable, already sliced by about a third. An admirable long-term goal would be government providing a dedicated funding source like a bond issue that could not be cut and would allow theaters to have a reliable bedrock budgeting figure. Some day.

So it’s up to the theater community to follow the money. The usual suspects are claiming to be tapped out. Instead, focus efforts on new fresh targets. The money is in the deep pockets of philanthropists, corporations and relocating international businesses. Add targets by moving your crosshairs to smaller companies as well, not just the mega-corporations. Few theaters have hit them up and they may simply need to be courted. Like independent book store owners hawking their wares, theater has to be hand sold to patrons and donors with the kind of personal attention that Dramaworks and the Maltz invest. If the staff is too small or overloaded to do that, then members of the board should take up the task, especially inviting appropriate people to join the board.

Unfortunately, donors usually want naming rights to something concrete like the stage or the bathroom mirrors. But what is obviously needed far more desperately is operational and marketing dollars. That’s why bringing in patrons to watch rehearsals and making them “producers” of a particular show is a smart move. The ultimate financial goal at this juncture is to attract endowments for operating expenses rather than seeking contributions toward bricks and mortar.

There are also “new” retirees from upper middle- income families now looking for somewhere to invest their income. Case in point: Actors Playhouse recently mounted Becky’s New Car, a play commissioned by Seattle real estate broker Charles Staadecker as a present for his wife’s 60th birthday. Since then, Charles and Benita have helped match patrons to playwrights and their efforts have led to 19 commissions. They are banding with friends to split up the estimated $25,000 cost of commissioning another new play themselves. Sharing the burden costs each backer about $3,000 a year for two years or $250 a month – less than the cost of leasing a car, he said.

How To Succeed in Business Without…

There’s not much fun in taking care of business, but more artistic directors are wisely paying more attention to the balance sheet. Mosaic’s Executive/Artistic Director Richard Jay Simon has been hiring freelance directors for some shows to enable him to spend more time ensuring Mosaic’s fiscal future. In fact, theater administrators need to invest more time in training staff members with an eye for taking over years from now – or just during vacation.

The key business facet that needs more attention is strategic business planning. As we advised in the last piece, the board and the administrators have to figure out what its priorities are five years down the line so it knows where to invest its limited resources today. What changes do they want to make? What happens if they lose their current space? What do they do if a hurricane knocks out one production? What happens if the artistic director gets hired away by another company?