Pioneering South Florida theater impresario Brian C. Smith was one man housing a half-dozen clashing personas.

He proudly produced commercial flypaper-thin comedies while bankrolling thought-provoking dramas. He was adored by many colleagues and fell out with others to the point of litigation. He drove a Rolls Royce when his finances allowed but stored possessions at friends’ homes when cash was scarce.

And over 30 years, he helped transform South Florida stage culture from predominantly dinner theater to the beginning of its national reputation for serious theater.

Smith, 70, died just before midnight Tuesday under hospice care in his home in Lauderdale Lakes, according to his close friend Darcy Shean who spoke with his family. He had been suffering from several ailments including kidney failure.

‘Brian saw a place in South Florida for professional quality theatre, and by sheer will, forced it to be,’ said another close friend , David Joyce. ‘He was certainly largely responsible for laying the foundation of what is now a vibrant creative community.’

The flamboyant actor-director-producer opened, managed and shuttered at least five theaters in South Florida including the Sea Ranch Dinner Theatre. At his Oakland West Dinner Theatre he presented both The Odd Couple and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.

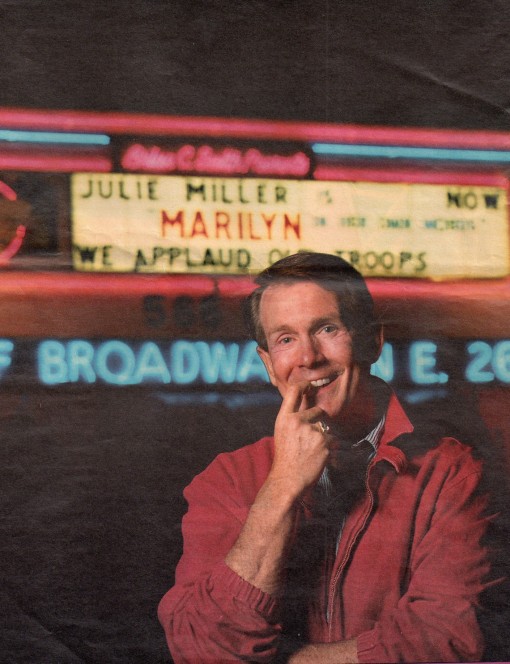

His last venue was a movie house in Wilton Manors whose marquee read from 1988 to 1999, ‘Brian C. Smith’s Off Broadway Theatre on E. 26th St.’

Jan McArt, founder of the Royal Poinciana Dinner Theatre, recalled her occasional leading man as a charismatic and irreverent personality. ‘He was tall and slender and very full of beans, full of energy.’

Joyce added, ‘He was one of those rare people who could meet you for the first time and make you feel, in a room of 400, like the only person there. And it didn’t matter if you were a movie star or a busboy, he made you feel special.’

Smith unapologetically pursued mainstream success with a string of Jewish-themed comedies even though he was not Jewish himself. Not relying on subscriptions, Smith also extended smash hits for months longer than originally scheduled.

His company was one of the few for-profit regional theaters in the country and he rejected suggestions that he become a non-profit operation. ‘If theater can’t stand on its own and people don’t come in and pay to see it, then why bother with it?’ he told the South Florida Sun-Sentinel’s Jack Zink in 1998.

But he believed in a profitable market for challenging shows that few others would attempt. He called his last venue the Off Broadway theater because he sought out plays with the quality and intellectual challenge of New York’s edgier theater. He produced the region’s first sex musical with nudity, Let My People Come and a touring company of Vinnette Carroll’s Don’t Bother Me, I Can’t Cope, the first major all-black show to play in Fort Lauderdale. In the latter half of his career, he produced dramas with gay themes such as the groundbreaking The Boys in the Band and the AIDS play, The Normal Heart.

Besides early Neil Simon warhorses, he produced complex dramas such as A Shayna Maidel , M. Butterfly and a stage version of Kiss of the Spider Woman. His later Jewish-themed plays may have been comedies but they dealt with broader issues of cultural identity and assimilation.

Tony Finstrom, his friend and a playwright, remembers working for Smith when one such play, Beau Jest, became a smash hit.

‘Five of us were in that tiny box office every day taking in ten thousand-a-day, ten thousand-a-day, ten thousand-a-day. It was exhausting, but Brian was dazzled by all that money,” recalled Finstrom. “He suddenly reminded me of Max Bialystock in The Producers, as he flaunted his success with his flashy cars and big parties in his lovely waterfront home.’

While his primary yardstick was box-office receipts, he also cared about quality. In the 1990s, Smith closed Breakfast With the Mittlemans in previews, rejected King of the Schnorrers just before auditions began and shut What’s Wrong With This Picture! a week early.

Smith told the Sun-Sentinel in 1991 ‘It’s not a matter of money; it’s a matter of pride,” he said. ”I could run this show for several more weeks but I won’t. It’s my theater , my name, and I don’t see what I want to see on the stage.”

Much of his career was spent juggling finances. He kept the Off Broadway shuttered for months in 1998 when he felt he saved money staying closed until he found a guaranteed money maker rather than lose money on a flop.

Eventually, after letting staffers go, he was locked out of the theater in the summer of 1999 for non-payment of rent.

Smith was always publicly optimistic about the financial reversals. “Am I depressed? Yes. Have I been depressed before? Yes,” Smith told the Sun-Sentinel in 1999. “It was a dangerous gamble. It turned out to be too dangerous.” He said he had paid more attention to upgrading the theater and less to paying the rent.

In the same 1999 interview he said, “This isn’t going to be my theatrical epitaph. I still have a lot of plays in me, and I’ll produce them somewhere.’

The Off Broadway was his final stab at being a major force in local theater. In recent years, he suffered from arthritis and knee troubles, but he continued writing and working as an uncredited script doctor.

Smith was born June 11, 1940, grew up in New Rochelle, N.Y., and went to college in Los Angeles before entering the Marines. He began acting in northern Florida in the 1960s and became the leading man for the Gold Coast Players around 1968, a troupe that played condominiums and restaurants. In 1969, he became its producer.

In 1971, he commandeered the banquet room of the beachfront Sea Ranch Hotel in Lauderdale-by-the-Sea as a dinner theater to entertain the wives at a visiting convention. He stayed six years, although he shut the operation for two months in 1974 when audience members objected to the strong language in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf.

In 1977, Smith started the Oakland West Dinner Theatre in Lauderhill, which lasted until late 1982 when the sluggish economy and dwindling audiences for dinner theater caused squabbles among investors.

He also opened theaters in Boca Raton and the Marco Polo Hotel’s Persian Room in Sunny Isles.

For five years, he resumed acting on stage and appeared small roles on film such as Cocoon: The Return, as well as flipping real estate properties.’Then in 1988, Smith took out a mortgage on his home and joined two other investors to lease the defunct Manor Art Cinema in Wilton Manors. The staff pulled out the first four rows to make room for the stage, built a proscenium and retrofitted it with lights.

Smith was still arguing with inspectors about potential building code violations 90 minutes before he opened the first show — with fire trucks standing by as a precaution.

That show revived John DeGroot’s Hemingway drama Papa with Bill Hindman. Its success led Smith to co-produce the show on the original Off Broadway in New York with Len Cariou.

Joyce said, ‘When the rest of the world was saying, ‘that can’t be done,’ Brian was saying ‘Watch me’ and he was usually right and often successful.’

Shean recalled,’ He was just a force of nature’. It was a grand ride.’

Survivors include brothers, Kevin C., Stephen, and Barry P.; one sister, Moira V. Tully, 15 nieces and nephews. His long -time partner John Bowman ‘Jay’ Tompkins III died in January 2009. An announcement about services is pending.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design

5 Responses to Brian C. Smith 1940-2010