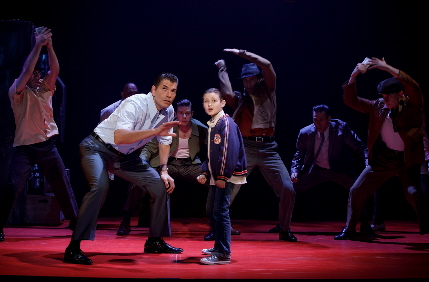

Mobster Sonny (Joe Barbara) advises Young Calogero (Shane Pry) how to throw dice at a crap game in A Bronx Tale’s national tour / Photos by Joan Marcus

By Bill Hirschman

The national tour of A Bronx Tale is proof that if producers hire enough really talented people, you can make an inarguably entertaining musical out of damn near anything.

There’s a moment in A Bronx Tale — when a grinning corps of murderous mafioso are singing and dancing like the waiters in Hello, Dolly! — that this critic started imagining Godfather the Musical, including a Twyla Tharp ballet when Sonny Corleone is shot to pieces at the toll booth and a punny vaudeville turn with Julie Taymor puppets chirping about how Luca Brasi is sleeping with the fishes.

A Bronx Tale should not work as a musical. A Bronx Tale has no business being A Big Brassy Broadway Musical because its source material is more complicated and deeper than the big strokes and the manipulations that characterize that sub-genre.

But here you’ve got proven experienced talents like composer Alan Mencken (once again echoing period musical genres), an A-list design team of past Tony winners, a fine corps of performers some of whom did their roles on Broadway, acclaimed choreographer Sergio Trujillo who just won a Tony for Ain’t Too Proud, and the veteran director Jerry Zaks (especially Jerry Zaks) – all of whom inject every unnecessary but perfectly calibrated and calculated Broadway Musical Theater Trope in the handbook whether it fits the original material or not.

So fight it if you must, but this musical fairy tale version of Chazz Palminteri’s 1989 semi-autobiographical one-man play and then the 1993 movie, somehow charms an audience who leave the evening with a satisfied grin and gratitude for two hours well spent.

All of the versions have the same basic premise as the adult Calogero narrates a look at his past: the 9-year-old kid in 1960 gets taken under the wing of the local capo Sonny after he sees him murder someone in the street but doesn’t rat on him under questioning. Calogero’s father Lorenzo, an upstanding bus driver, understands the realities of living in a neighborhood ruled by the mob, but he discourages the boy from interacting with the increasingly adoptive Sonny.

Both give the kid fatherly advice: Lorenzo says follow your heart as they toss a baseball around; Sonny says never trust anyone and to rely on fear rather than love as a motivation — as he has the kid tossing dice at a thousand-dollar crap game.

Calogero’s dad, of course, is no wimp and courageously faces down Sonny to try to save the soul of his son.

Eight years later, the teenager has succumbed to doing harmless errands for Sonny for more money than his dad can earn and being drawn deeper into the culture. His straight arrow father grows increasingly worried as Calogero goes through the normal rebellion of adolescence, driving him closer to Sonny.

Sonny, of course, other than being a conscienceless murdering animal, has a heart of gold when it comes to the kid, handing down lessons of cold pragmatism drawn from his having read “Nicky” Machiavelli” (That’s the title of one song). Much later, Sonny inexplicably and contradictorily also tells him – just like his dad – to listen to his heart.

This obviously sets up a tug of war between competing role models, but they agree on Lorenzo’s dictum: “The saddest thing in life is wasted talent.”

Complicating matters in a time of unbridled and vicious bigotry is that our hero gets a forbidden crush on Jane, a black girl in his high school.

Palminteri wrote the script which, like so many musical adaptations, ticks off the key points of his original work from an outline in between production numbers and ballads. The original play was a major surprise in its humor and insight. This version retains some of his great lines like Calogero saying of the aftermath of some minor wrongdoing, “It was great to be Catholic and go to confession. You could start over every week.”

But the need to put on a musical keeps getting in the way. The second act opens with Jane and her girlfriends singing a rousing shoop-shoop number which does nothing to advance the plot or deepen characterizations; it’s just that all Broadway artists know you need a peppy number to kick off the second act. At the same time, it is performed with winning pizzazz.

Mencken’s tuneful score gleefully embraces sidewalk do-wop, some Sinatra-tinged pop, nascent R &B and other genres all trying to hide that at heart, these are classic Broadway show tunes. That’s not a bad thing; Mencken is a master at spinning thoroughly an engaging score you can’t remember well enough to sing a single number in the car on the way home.

Slater wrote the lyrics to The Little Mermaid, Sister Act, School of Rock and (for his sins) Love Never Dies. In other words, he’s a solid craftsman who has rarely written anything to threaten Stephen Sondheim or Lin-Manuel Miranda.

Robert DiNiro, who championed the play to be a film and played Sonny in it, is credited here as co-director – reportedly his first foray into theater. He may or may not have actively directed here. Who knows? But the staging is clearly Zaks’, who has helmed everything from Little Shop of Horrors to Six Degrees of Separation, the new Bette and Bernadette Hello, Dolly! to Smokey Joe’s Café.

As mentioned, the design team is the best, from Beowulf Boritt’s skeletal outlines of homes and fire escapes against blood-red backdrops adorned with line drawings, to William Ivey Long’s period costuming especially Sonny’s sharkskin suit and shirt with long triangular lapels. A major expense in the budget must be vats of Brylcreem doused on the male cast members’ hair.

Zaks has chosen and guided a capable cast, although some of the men have trouble with the higher notes in the register, but everyone has a solid Bronx brogue even when singing.

Joey Barreiro, a Miami native and an alumni of the University of Miami and Coral Reef Senior High, exudes the crucial geniality as the adult and teenage Calogero to make the audience care about him and to carry us through the evening. With a warm grin and a shining dark eyes, he echoes a Tony Danza vibe.

Tall and handsome Joe Barbara, who has appeared in Grease and Jersey Boys, is the standout as Sonny with just the right aura of self-assured swagger for someone who knows he is the king of the forest. The script forces him, as with most musical comedies, to shoehorn in the few subtler aspects of his character with a passing single line, but Barbara does it smoothly.

Richard H. Blake, who originated the role of Lorenzo on Broadway, amazingly manages to make the father a warm, three-dimensional human being.

The role of Young Calogero shifts between youngsters. Opening night we had the round open-faced blond-headed Shane Pry who was simply delightful, especially leading the kickline of murdering mobsters in “I Like It.”

A Bronx Tale from Broadway Across America plays through June 23 at the Broward Center for the Performing Arts, 201 SW Fifth Avenue, Fort Lauderdale, as part of the Broadway Across America series. Performances are 8 p.m. Tuesdays-Saturdays, 2 p.m. Saturdays and Wednesdays, 1 and 6:30 p.m. Sundays. Runs 2 hours including one intermission. Tickets $40-110. For tickets visit www.browardcenter.org; by phone 954-462-0222.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design