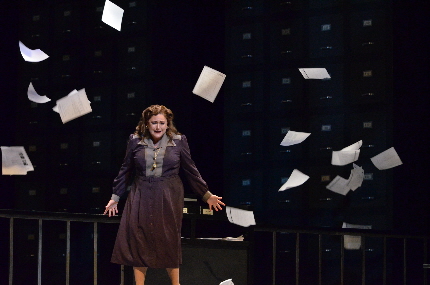

Kara Shay Thomson as a distraught Magda trying to get a visa from a soulless bureaucracy in Menotti’s The Consul at Florida Grand Opera / Photo by Brittany Mazzurco

By Bill Hirschman

Is it because Gian Carlo Menotti’s The Consul is in English that Florida Grand Opera’s production is so unusually effective? Is it the accessibility of the 20th Century setting or the still resonating themes of dehumanizing repression of a soulless bureaucracy? Is it the familiar sound of mid-century classical music?

Whatever factor or factors are involved, FGO’s season closing production of what may be Menotti’s greatest work is somehow far more emotionally potent than fairy tale stories of ancient star-crossed Egyptian beauties and 19th century abandoned Japanese naifs wailing repetitively in languages you don’t understand.

The Kafkaesque tragedy depicts the wife of a dissident in a nameless totalitarian society who struggles to wrest life-saving visas for her family out of the Byzantine bowels of a foreign consulate. The office is headed by the never-seen inaccessible title character but buffered by a seemingly pitiless secretary who drowns all comers in a mountain of endless paperwork.

She sings, “Your name is a number / your story is a case / your need is request / your hopes will be filed.”

FGO’s first run at the piece results in a gut-wrenching expressionistic nightmare of the unfeeling destruction of humanity by the very societal structures it has created for its protection.

Don’t discount either the decidedly American feel to Menotti’s music and lyrics, even when the notes wax as melodic as Puccini and the words as poetic as Byron.

And, above all, don’t skimp on credit to a cast of singers who infuse the dark even depressing tale with the raging outsized passions only credible in this particular art form (shaped by Julie Maykowski in her FGO directing debut and former FGO resident conductor Andrew Bisantz).

Soprano Kara Shay Thomson, who starred in FGO’s Tosca last year, wrung every ounce of passion from proletariat everywoman Magda. Her second-act closing aria more than earned the extended ovation from the opening crowd as Magda pled to see the consul and then exploded in a denunciation of the heartless machine

As her mother, mezzo Victoria Livengood similarly stopped the show with her first act lullabye to her infant grandson dying of cold and hunger and sickness. Livengood worked for Menotti who died in 2007. She certainly brings a more full rounded classical opera sound to the score with impressive power sustaining her delivery from her top notes to the basement register, often within a couple of bars of music. But she also delivers the universally recognizable maternal qualities necessary such as the very un-operatic passage when she sings baby-talk to the child.

As the wounded revolutionary husband, Keith Phares doesn’t have the same amount of stage time, but the GQ-handsome hero has a commanding pure baritone that, when singing English words, is as plausible and convincing as anyone can be singing grand opera. Phares set hearts aflutter, as they say, when he played Orin in 2013’s memorable Mourning Becomes Electra.

Also up to her role was Carla Jablonski as the by-the-numbers secretary who is seemingly an unfeeling creature immaculately whelped by the system. Her brief opportunity to show the cracks in her certitude in the third act were not quite as credible as they might be, but her mezzo was well-suited to the secretary’s consistent rebuffs to Magda’s pleas without ever boring the audience.

The orchestra – a bit smaller than usual – seemed note perfect to these ears as it alternately swelled with the tumultuous melody, but also allowed for individual instruments or small clusters to be heard clearly, such the poignant plinking of a solo piano. The players shone in the long underscored passages while the sets slowly changed.

A quick shout out to the borrowed Seattle Opera’s drab, oppressive settings of Magda’s tenement apartment and the consul’s demoralizing waiting room dominated by towering stacks of file cabinets containing tens of thousands of applications – all expressively lit by Kevin G. Mynatt.

For those unfamiliar with operas with English librettos or even American operas other than Porgy and Bess, The Consul illustrated the emerging break with the past that Menotti exemplified. It rests on a deep social message that few operas before it cared about other than true love never runs smooth. There is no overture, not even an extended musical introduction. The only real opportunities for the audience to applaud come after the most famous arias and at the end of each act. Snatches of dialogue are spoken not sung. The libretto itself is more lyrical and just plain believable than in most Italian/French operas. The endless repetition of a line of lyric just to show off vocal dexterity rarely occurs until the third act. Granted, modern composers and fans of the American musical would suggest that Menotti could have effortlessly sweated about 15 minutes out of this three-hour evening and thereby intensified its impact.

But The Consul should be required viewing for newcomers to opera trying to grasp the art form’s tropes because the accessible piece maintains enough roots in the past to help explain what the masters like Verdi, Mozart and Puccini were intending to accomplish.

While performance pieces about repressive totalitarian regimes and corporate structures had graced the legitimate stage for decades, The Counsel came on the cusp of the The Cold War and the Red Scare. The irony is that the attack on soulless bureaucracy resounds just as vibrantly today.

Menotti who wrote numerous operas including the shorter The Medium and The Telephone won wide fame for his 1951 work, Amahl and the Night Visitors, commissioned by NBC television and rebroadcast several times during the 1950s and 1960s.

But The Consul was his first full-length opera. The show bowed not at the Met, but on Broadway produced by Efrem Zimbalist Jr., yes, of 77 Sunset Strip and The FBI but also the son of a famed conductor and singer. It won the Pulitzer Prize for music and the New York Drama Critics Circle Award for best musical in 1950. Just for the record, you may hear that the show won the 1951 Tony Award. Well, sort of. Lehman Engel, a legendary composer, educator and producer of original cast albums, won the Tony for conductor and musical director (a category no longer in existence). The Best Musical Tony that year went to Guys and Dolls and the Best Score nod to Irving Berlin for Call Me Madam. Just saying.

FGO arranged free shuttle transportation the first weekend to the Arsht from the Broward Boulevard Tri-Rail station, which has free parking. FGO plans to do the same for Broward patrons next season for selected performances of The Passenger in April and Don Pasquale in May. It’s arranging a similar service next season in Hialeah.

Florida Grand Opera performs The Consul through May 16 at 8 p.m. Tuesday, Friday and Saturday at the Arsht Center’s Ziff House, 1300 Biscayne Blvd., Miami. Tickets $19-$180; (800) 741-1010. More information at fgo.org.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design