By Bill Hirschman

By Bill Hirschman

Awash in issues of Arab-American assimilation and Anglo antipathy, Disgraced is the classic contemporary example of the topical, thought-provoking drama that forces you to revalidate, even reexamine your perception of the tumult around us.

When we saw it on Broadway last year we knew immediately that it would wind up at GableStage because it was such a perfect fit for the theater’s bent for intellectually stimulating fare –so clearly borne out by its beautifully executed and bracing production this month. We didn’t realize that producing artistic director Joseph Adler had been trying to get the rights since it bowed off-Broadway in 2012.

While Adler was one of the first to get the rights, he put it at the end of current season. Since then, Disgraced has become one of most-contracted plays by regional theaters. One recently closed in Chicago and another plays as we speak in Durham, North Carolina; a 30-city national tour begins soon and it’s being adapted for an HBO movie.

But GableStage gives it a solid iteration that will have many audience members rethinking some core assumptions.

Ayad Akhtar’s 2013 Pulitzer Prize winner is the latest in a spate of post 9/11 plays about – and, more importantly, written by Arab-Americans – about a host of interlocked issue. In this case, its Arab-Americans attempts to find their place in a Western society, played against the lingering if politely repressed fury, fear and prejudice of mainstream Americans against Muslims. It asks our nation of immigrants whether anyone can choose or be allowed to or even should want to assimilate, an issue that must resonate with Cubans, Jews, Italians, Irish and any other group that strives to “fit in” or not.

Disgraced puts four latter-day liberal yuppies from different backgrounds in the crucible of a dinner party among spouses and business associates.

During an evening of gourmet salad and sophisticated banter, the initially invisible fault lines between cultures crack wide open, leaving devastation in every direction. It is a scalding rebuke to anyone who thinks that any section of our society has come to an intellectual or emotional homeostasis about social, cultural and geopolitical divisions.

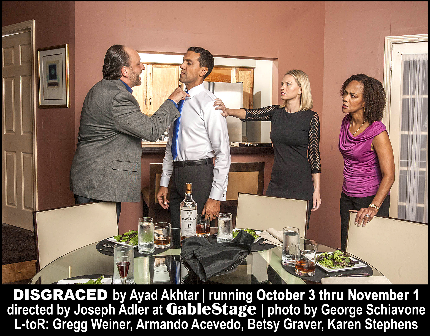

The confrontation occurs in a sun-kissed apartment on the Upper West Side owned by a middle-aged couple out of Vanity Fair: Amir Kapoor (Armando Acevedo), a smoothly handsome mergers and acquisition lawyer American-born and Muslim-raised; and his wife, Emily (Betsy Graver), an equally gorgeous WASP artist whose work is rooted in her interest in Islamic culture. From all appearances, they are a close and loving couple.

Amir is on the cusp of becoming a partner and Emily is about to have a breakthrough due to Isaac (Gregg Weiner), a Jewish museum curator who wants to exhibit her work at the Whitney. Isaac is also married to Jory (Karen Stephens), an African-American lawyer who is also an up-and-comer in Amir’s firm. All four are to meet at the Kapoor condo for a dinner.

But a problem emerges. Amir’s nephew, Abe Jensen (born Hussein Malik in Pakistan) (played by Angel Dominguez) is upset that a local imam has been arrested on what he believes are bogus charges of financing terrorists. Abe contends that it is solely religious persecution. Neither man is especially devout although both were raised in the faith and then let it slide into inconsequentiality. Abe wants Amir to intercede as a lawyer and respected member of the mainstream community. Amir, who has spent his life pointedly repudiating his heritage and religion, balks until Emily pressures him to help.

But his appearance in court for the imam, solely as moral support, gets mentioned in an article in The New York Times. Serious fallout begins to shred Amir’s career and his relationship with colleagues and neighbors.

Which is when these power couples meet for a prototypical civilized dinner. The talk about Amir’s involvement in the case leads to a broader discussion of Islam itself. Isaac is the one who makes the distinction between the admirable religion and how it has been appropriated by terrorists. Amir is at first highly critical of the faith’s failings, but ends up defending its virtues and accomplishments.

Quickly, buried prejudices erupt. What began as an intellectual dorm room debate billows into an antagonistic clash. It culminates in shocking and thoroughly unexpected violence (the exact nature of which we won’t reveal).

One of the most fascinating aspects of the script is how the four major characters begin espousing and pursuing one point of view, but who end up in a much different place – sometimes simply revealing their true feelings and sometimes because of revelations that are a surprise to them as well. For instance, Isaac is a classic urban liberal full of even-handed admiration for Amir; Emily embraces the positive elements of Arabic culture, including the Muslim religion, as an inspiration for her. And of course, Amir believes that he has consciously rejected all the traditional aspects of his culture and feels not just a lack of kinship, but to some degree espouses being repulsed by much of it. None of that will stand when the fragile civility of social interaction begins to erode.

Perhaps the second-most shocking but crucial element of the play is when the two Arab-American characters admit in different parts of the play that America did indeed bring 9/11 upon itself by its arrogant insistence that the Muslim world with its roots in antiquity instead adopt the “enlightened” Western culture. What’s shocking is not the statement, but that Ahktar, who clearly does not agree with it, lays out an unnervingly cogent and nearly persuasive case to support it. In a time when young people on both sides of the world are joining ISIS, these arguments force the audience to at least pause and reassess – not terrorism – but our complicity in the world we live in 2015.

The terrible irony here is that Amir, who was born here of Pakistani immigrants, sees himself as American, no hyphen. Chocolate-skinned and inescapably Semitic, he has worked hard enough to mold himself in the image of a GQ sophisticated Wall Street type. In a way, it echoes the Jews’ outlook in Germany during the Weimar Republic who doubted anything would happen to them because, after all, they were Germans. He thinks his wife is romanticizing the Arabic culture and selectively ignoring the less pleasant aspects of Muslim theology and practice.

It is not a criticism that the play benefits mightily that the shocking statements and the aforementioned linchpin moment were truly stunning – a carefully-chosen word — when we saw the show in New York. So it’s hard to judge the show’s tone upon seeing it for the second time. There is nothing muted about this perfectly valid production, but the New York one seems in retrospect to have had a tougher, sharper edge to it. But that may be from knowing what’s coming.

This was the first major play script for Akhtar, whose career had been primarily as a novelist. Some observers have criticized the evolving plot as quite schematic and mechanical. But as naturalistic as the play is, it’s still theater with such tropes expected to be accepted. Regardless, the concepts and emotions swirling about are compelling. Akhtar has constructed a Rolex-running piece that deftly sets up a situation and then follows it fearlessly to its logical if catastrophic conclusion. His dialogue is convincingly naturalistic with few flights of fancy verbiage, but his characters speak with that facile, mildly witty verbal intercourse expected from such players.

We’re fond of saying that one of Adler’s strengths as a director is his invisibility. He sees no need to direct in a flashy way that draws attention to himself. But on reflection, that’s wrong. Adler certainly trusts the people he hires, many of whom he was worked with for many years. But nearly everything you see and hear on stage has been carefully molded and guided to his vision, certainly refracted through the prism of his aesthetic.

The performances under Adler’s direction are nearly flawless. Acevedo, with his chiseled jaw and piercing eyes, seems like a handsome hard-charging Wall Street type indistinguishable from a thousand others except for a darker skin tone. Acevedo’s Amir exudes a smile that seems cordial. But even in the beginning you may detect the slightest bit of anxiety of someone struggling with something. He exudes a hard-won dignity that he is secretly aware is fragile and vulnerable. He feels himself on the cusp of something.

Graver is a lovely blonde woman with a flighty voice who looks and sounds like she was a cheerleader at some point. But while she can play a lovable dimwit as she did in Actors’ Playhouse’s Fox On The Fairway, usually she convincingly inhabits women who reveal considerable depth such as the heroine in GableStage’s Venus in Fur or Arts Garage’s Lungs. Here, she is perfectly cast as the generous-hearted and highly intelligent artist Emily. When Emily holds forth on the glories of the Arabic culture or the complex virtues of her own paintings, Graver’s passionate delivery makes it totally believable. Graver also makes Emily the most emotionally honest character and the one we immediately bond with.

Stephens (one of the region’s best actresses and a co-host with me on Spotlight on the Arts) gives another fine gem of a performance of an assured intelligent flinty achiever who is comfortable with a success that she, too, has earned.

Just as fascinating is watching Weiner persuasively depict the supposedly enlightened and broad-minded Isaac slowly revealing the pent-up paranoia, resentment and anger that still simmers in even the most bleeding heart liberal since the Twin Towers fell.

Disgraced runs through Nov. 1 at GableStage, 1200 Anastasia Ave., Coral Gables, inside the Biltmore Hotel. Performances generally at 8 p.m. Thursday-Saturday, 2 p.m. Sunday and some Saturdays, 7 p.m. Sunday. Runs 80 minutes with no intermission. Tickets are $37-$55 and students $15. For tickets and more information, call 305-445-1119 or visit GableStage.org

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design