Associate Pastor Jordon Armstrong squares off against Pastor Timothy Gore as Rita Joe watches in Outre Theatre Company’s The Christians / Photos by Kay Renz

The “regular” South Florida theater season (ignoring that the summer is filled with offerings as well) is fully underway. Three openings last week, five this week, four in another week or so. If you don’t see a review or a feature you are looking for, it’s either already posted further down the main entry page, listed by pressing the “Reviews” tab on the teal and white rail, or it’s coming soon. There will likely be something new posted nearly every day.

By Bill Hirschman

All too apropos for our bitterly divided time, Outré Theatre Company’s intellectually stimulating production of Lucas Hnath’s The Christians asks what happens when two sincerely held but diametrically opposed viewpoints inescapably clash.

Hnath doesn’t try to answer the question other than to depict the inevitable tragic fallout and Outre’s edition is even more careful to even-handedly portray that both combatants harbor weaknesses underneath their altruistic passion.

Yet each champion contends with as much absolute conviction as the sun rises in the east that they are acting on what they genuinely believe God is saying to them and their conscience. Their mirrored anguished sincerity and selflessness are what elevates The Christians into a fascinating dissection of organized religion, acting with Christ-like compassion in real life, having faith in unpleasant doctrine that you still believe in, and seeking His truth amid conflicting liturgy and philosophies.

The Christians opens inside a service at one of those mega-churches you see on television, complete with (they genially joke) “a baptismal font the size of a swimming pool” and multi-media projections displaying images of hellfire, of doves and of specific verses referenced in speeches.

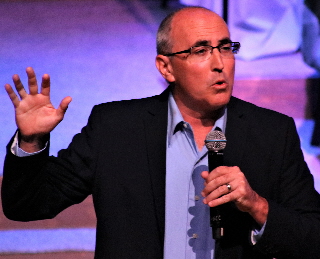

After a choir’s hymn, Pastor Paul (Timothy Gore) begins his sermon to us his congregation with the house lights still shining. It’s a gentle leisurely-paced friendly address that will last an uninterrupted 20 minutes or so. It will take that long because the born storyteller, who looks like the trustworthy insurance executive next door who borrows your lawnmower, is easing his congregation into cataclysmic territory.

He tells a story he heard at a conference about a boy who died saving a child’s life during a house fire in Africa. But he says his clerical colleagues believe the boy went to hell because he hadn’t accepted Christ as his savior (indeed, he didn’t know about Him).

Paul preaches to his loyal parishioners that there is no hell. He believes that God and Jesus redeem everyone regardless of whether they are believers or what they did in their lives; it’s all blasted away with the purge of God’s grace. Everyone goes to heaven. Everyone. “We’re no longer a congregation that says ‘My way is the only way,’ ” he announces.

Asked to continue the service with his regular prayer for the sick, the young scruffy Associate Pastor Joshua (Jordon Armstrong) reticently expresses his profound alarm that this view contradicts the core of Christianity of two millennia. The two men spar citing Scripture and their interpretations of it, pitting God-given rationality versus faith. Paternalistically and confidently, Paul calls for a vote of confidence from the congregation that tops four figures. Joshua, a quiet firebrand for several years, overwhelmingly loses the vote and leads 50 parishioners away to start a new congregation.

But over the next few days, a swell of others defect as well. The controversy has unnerved the church board of directors, according to Elder Jay (Timothy Mark Davis). Over the rest of the play, not-so-holy internal politics will interfere as the church loses more and more of the faithful – and their financial support.

Timothy Gore

Paul’s primacy is especially undercut in a Sunday service by a divorced single mother (Shannon Ouellette) who is barely scraping by, yet tithing more than her share because the church has been her supportive home through troubled times. She gingerly seeks guidance from Paul by publicly asking questions suggested by her new boyfriend as well as the community at large For instance, would Hitler be forgiven and be in Heaven? Is Paul’s vision as unbending as Joshua’s?

At the same time, Paul’s personal situation deteriorates when it turns out that he has been a bit manipulative with the congregation by timing his long-troubling epiphany until the church’s mortgage was paid off. Worse, his beloved wife Elizabeth (Rita Joe) and teacher in the church realizes that he has not trusted her enough or respected her enough to tell her of this change of heart before he sprang it on the congregation. It widens what were likely barely noticeable cracks in their marriage.

In the end, no one is a hero, no one is a villain.

For the broad-minded theatrical audience, to stereotype them, Paul’s new humanistic philosophy seems a welcome relief from the strict dogmatic approach of many high-profile practitioners. Joshua seems less imaginative, more unbending and less compassionate by adhering to the doctrine for its own sake, not his parishioners.

But over the arc of the play, we see Paul as a more flawed individual. Further, we learn to have more compassion for Joshua during his late second act description of his mother on her deathbed refusing to accept Jesus because it would mean her last breath would be a lie. Joshua is clearly in agony because he is certain he will never see his mother again except looking down from heaven into the pit of hell where she will writhe for eternity.

Jordon Armstrong

Director Skye Whitcomb delivers some of his finest work, including bringing out some of the best performances we’ve seen from these actors. Notably, this is yet another step up on Armstrong’s steady growth as evidenced in his recent work in New City Players’ Constellations. Here, Armstrong creates a man who is not some unthinking rigid fundamentalist, but someone who cares deeply about people and has paid a terrible price for his faith. His tormented aria about his mother’s death is a standout moment in the new season.

Especially laudable, Whitcomb encourages, even insists these characters take their time to consider how to say what they are about to say. He lets the pacing breathe so it appears people are actually weighing what other people are saying to them. Sometimes these people, no matter articulate or inarticulate, are searching for the right words. Even though they are speaking into hand-held microphones and even “narrating” some scenes, as Hnath dictates, it is absolutely credible and naturalistic.

Gore, whom we’ve seen here and there over the years, nails Paul like no other role we’ve seen him do before. His measured phrasing echoes pastors you’ve heard before. He wins you over with a persona resembling an open hand extended to ease your way. His subtly shaded performance exposes Paul’s shortcomings in glimpses – faults he might not have been aware of himself until he is forced to acknowledge them.

Rita Joe turns in yet another performance worth seeing. She looks adoringly at her husband during his sermon, but her nurturing support disintegrates as she realizes that there has been more of a gulf in the marriage than she had acknowledged. Ouellette, too, is completely credible as a young woman torn between her allegiance to a church that has saved her in multiple ways and the questions that are eating away at her.

Hnath, one of the country’s most promising playwrights, debuted the work at the Humana Festival of New Plays in 2014, which this critic saw and led him to nominate it for the Steinberg/American Theatre Critics Association New Play Award. Humana had a much larger budget that featured a gorgeous set worthy of a Texas mega-church plus a large choir. Its preacher was more of the highly charismatic figure you’d see on a Sunday morning television program. Outré has a more modest presence partly for budgetary reasons, but also by choice. Both approaches and performances are equally valid.

A word about Outré: This peripatetic company has struggled throughout its existence in part because it takes envelope-pushing chances no one else will take, other than Thinking Cap Theatre, Mad Cat and Island City Stage. Sometimes it has produced home runs like its Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson and Thrill Me; sometimes other earnest productions were crashing failures better left unnamed. Other companies are more consistent, but others don’t reach for something more than what’s expected. So Outré is still capable of delivering head-scratchers. But the quality of their work on entries like The Christians, or last season’s Hedwig and the Angry Inch, are proof that if Outre is willing to take a chance, audiences should be willing to take a chance on them.

The Christians plays through Nov. 11 from Outré Theatre Company performing at the Pompano Beach Cultural Arts Center, 50 West Atlantic Blvd., south side of the road, one block east of Dixie Hwy. Performances 8 p.m. Thursday-Saturday, 2 p.m. Sunday. Running time 2 hours with one intermission. Tickets $42 adults, $20.50 students and industry rate. Visit www.ccpompano.org or call (954) 545-7800.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design