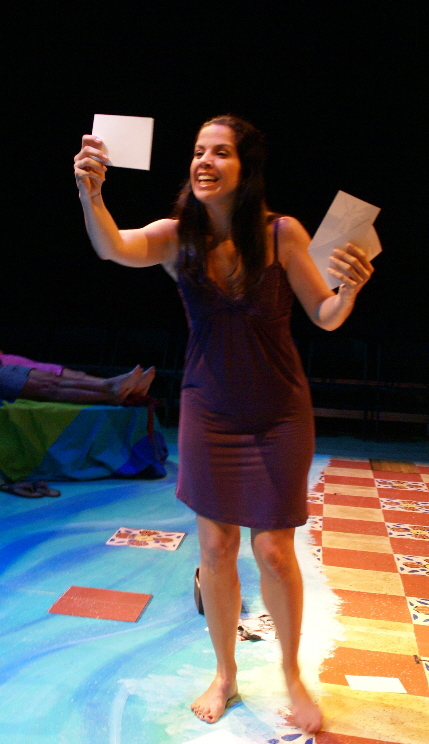

Tanya Bravo discovers her parents’ secrets in The Cuban Spring at New Theatre / Photos by Eileen Suarez

October and November are jammed with openings, as many as seven in one week. To find reviews of all the current productions, click on the “Reviews” tab in white letters in the teal bar in the upper left-hand corner.

By Bill Hirschman

The overall picture may seem a bit disjointed and fuzzy, but the world premiere of The Cuban Spring at New Theatre incisively depicts the complexities of Cuban-American families in modern Miami as their American-born generation conflicts with parents struggling with ghosts of their birthplace.

Even Anglos can hear the deafening resonances in Miamian Vanessa Garcia’s insider look at the tidal push and pull between a generation forced to create a new life in America while their hearts remain 90 miles overseas, and their children for whom Cuba is only a cultural touchstone and the source of countless bedtime stories.

Garcia doesn’t break new ground for anyone living the dilemma, but her valuable insight is that neither generation’s feelings are as simple as outsiders might believe. Some émigrés have desperately mixed feelings about returning and their children are increasingly intrigued at newly-opened opportunities to see the Old Country.

She documents the inevitable clashes with a three-dimensional vibrance, a sense of assured authority and an ability to elicit empathy for those caught in the vise.

If the relationship of all the pieces don’t quite hang together yet in this early edition, those pieces provide fascinating glimpses into the specifics of the swirling emotions. Garcia has filled the journey with insightfully-observed moments like when one Cuban instinctively objects to being grouped in with the Marielitos or balseros.

While some characters initially seem archetypes, director Ricky J. Martinez and a cast of skilled actors inject that necessary third dimension from the very first scene — essential for the play’s success because the characters don’t gain depth until Garcia starts revealing secrets that add layers to these denizens.

Set in 2011, the Arab Spring demonstrations toppling oppressive regimes has fired the imaginations of one Coral Gables family. The immigrant Miguel (Carlos Orizondo) secretly plots with his fiery younger brother Dio (Nick Duckart) to sail close to Cuban waters and set off fireworks to signal continuing solidarity with the beloved homeland. That plan gets short-circuited to the relief of his loving if slightly imperious wife Olga (Evelyn Perez).

The play’s fulcrum is their daughter Siomara (Tanya Bravo), a psychiatrist married to an African-American lawyer John (Ethan Henry). Siomara is inexplicably amorphously distraught, which we suspect much later in the play ties back to conflicted feelings about her identity.

When Miguel muses about his devotion to his country, his daughter Siomara asks, “What about me?” It’s a question that puzzles her father. She explains, “Well, I think because I’m Cuban too…” Her father cuts her off: “…You’re not Cuban, Siomara.” She protests, “What happened to all those years, growing up, when you kept telling me I was Cuban and I thought I was actually born there.”

Now trying to decide whether to carry through a pregnancy, Siomara’s need to know who she is drives her to uncover some of the secrets her parents have gently kept to themselves.

At one point, Siomara asks her parents’ blessing to visit Cuba, something that violates their commitment never to return until the Castros are gone. There is a terrible paradox in the parents’ almost physical hole in their being, yet Olga forbids their daughter to visit.

The script has many virtues, especially its gentle humor and Garcia’s embrace of images that communicate the heartache of loss

Miguel says to Siomara, “You, your generation, you take it all too

lightly. It’s. It’s home.” He recalls his recent 55th birthday. “I wake up and I think to myself: Why do I live here?… I think to myself: Why do I live in this house with this Spanish tile floor that came from God knows where and the fans that look like metal airplane propellers…. We made this house and I love it, and I’m proud of it, most days. But that morning I woke up and I felt like I’d woken up in another land, a strange land, a different shore. No se como explicartelo. I missed my father. I missed him desperately all of a sudden… It’s so sad I don’t know where to put it, this feeling.”

She also has a fine eye for simple domestic scenes that underscore her theme. Olga offers Siomara an avocado treat. “Taste this, Siomara, and tell me that this doesn’t taste like Cuba,” Olga says. To which, Siomara says with long-simmering frustration, “I don’t know what Cuba tastes like, Mom.” Her mother insists, “Yes, you do. It’s your blood. You know. Taste.”

Garcia deftly and subtly peppers the script with Spanish to illustrate differences in the characters. Siomara rarely speaks any Spanish aloud. Her parents mostly reserve Spanish for exclamations and endearments. But Dio speaks in a mashup of English and Spanish that Garcia brilliantly has John react to angrily since he, the outsider, knows so little of the language.

But the script needs work. The connections of the disparate pieces are never tied tightly. For instance, one “shattering” revelation about Miguel’s father is mentioned for about 15 seconds and then dropped into oblivion for the rest of the play, let alone its relevance or resonance made clear. And it’s only brainstorming after the performance that we have a glimmer of why Siomara is undecided about having a child.

Martinez, whose direction of last summer’s Gidion’s Knot was a career highlight, does a solid job here. He lets the play breathe, ending scenes with people silently reflecting as lovely guitar music hums. He gives the domestic scenes a sense that the audience is just peeking in the window. On the other hand, it takes the audience a while to catch up with what’s happening many times, such as why John and Siomara are at each other’s throats so ferociously in the second scene.

Martinez has cast the show beautifully. Orizondo, one of our favorite and rarely seen actors, brings a wonderful believability to the hangdog Miguel’s still bleeding heart. Perez has been playing a riff on this voluble matriarch for years, but never better than here. Duckart injects a wild card energy and vitality into the proceedings. Henry, one of the region’s best actors, is just as believable in his angry frustration at his wife’s crippling angst as he is in his abiding love for her.

Last but not least is former New Theatre mainstay Bravo who hasn’t been seen locally very much, so this is a welcome return home. From her first intense monologue about a dream of giving birth, she is a force of nature. She is totally American with a driving Type A personality that Bravo and Martinez are not afraid to make actually a touch off-putting. She can be dismissive of tradition while still honoring it.

The exact arc of The Cuban Spring, the motivations and a sense of a cohesive whole may be a bit elusive, but the journey remains worth taking.

The Cuban Spring runs through Nov. 2 from New Theatre performing at the South Miami-Dade Cultural Arts Center, 10950 SW 211th St., Cutler Bay. 8:30 p.m. Friday and Saturday; 1 and 5:30 p.m. Sunday. Tickets are $26 in advance, $31 day of show, student rush tickets, $16. The show runs 1 hour 45 minutes including one intermission. Call (786) 573-5300 or www.smdcac.org for information.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design