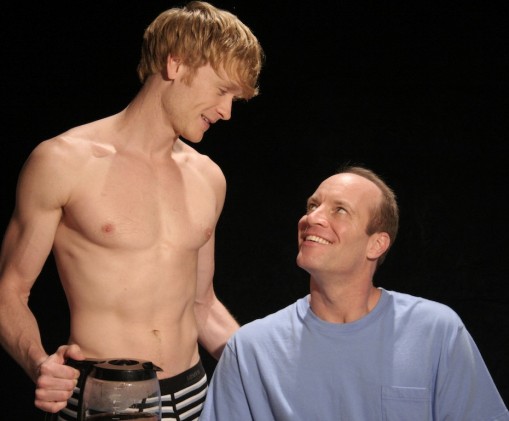

Joshua Canfield (left) and Tom Wahl star in "Next Fall" at the Caldwell Theatre. Photo: Dustin Hamilton

Ever since Next Fall became an off-Broadway hit in 2009, audiences have debated whether the comedy-drama is about the travails of gay life or the challenges of religious faith in the 21st Century or the improbable coexistence of the two in one person. It seemed a tad unsatisfying because it never resolved any of the three themes.

But under Michael Hall’s sensitive direction at the Caldwell Theatre Friday night’Next Fall expanded its vision, becoming a powerfully moving examination of the difficulty of maintaining the most intimate relationships despite profound differences between human beings.

Next Fall marks a brief return to directorial duties for Hall who co-founded the Caldwell in 1975 and handed the reins to Clive Cholerton in 2009.’Hall was not an infallible director and his stumbles were memorable. But his work here is inarguable proof of the insight, talent and skill he wielded much of the time.

Next Fall is a validation and valediction of Hall’s career: his excavating depths of meaning from scenes, his ability to nurture nuanced performances from actors, his impeccable timing of comic repartee, his willingness to let dramatic scenes breathe and his courage to let silences speak of characters’ unspoken words and bonds. The quality of Hall’s production here rivals the New York edition and sometimes surpasses it.

At the heart of Geoffrey Nauffts’ play is a gay couple in New York City. Luke is a fresh-faced young actor (Josh Canfield) who maintains a devout belief in Christianity; Adam is an older writer/educator (Tom Wahl), an agnostic whose jealousy over sharing his partner with Jesus impels him to persistently attack his beloved’s faith.

The play begins in a hospital emergency room after Luke has been critically injured in a car accident. Keeping vigil are a straight-laced but gay friend (the dependable Christopher Kent) and their New Age-ish employer (the endearing Irene Adjan) who describes herself as a ‘fag hag.’

Arriving separately are Luke’s divorced mother and father from Tallahassee, complete with a twang that sounds transplanted from Odessa, Texas. Once hellions themselves, the father (Dennis Bateman) is a tight-lipped born-again businessman, and his mother (Pat Nesbit) is a not-quite-recovering substance abuser long on charm and wit.

When Adam is the last to rush in from the airport, he desperately wants to see his lover. But he is stymied by the fact that Luke never came out to his family ‘ a situation that had been driving apart the lovers. When doctors finally allow only family to see the comatose victim, Adam cannot out his partner and stake his claim to see the man he loves.

Among the beautifully conceived, acted and directed scenes is when the stunned father returns from Luke’s bedside. The excluded Adam peppers the father with questions with a fervor that obviously exceeds the interest of a close friend.

The arc of the play bounces between the waiting room and scenes re-tracing the evolving relationship. It is complicated by Luke’s holding onto his genuine and sustaining faith while the frustrated Adam tried to chip away at the contradiction of a man who believes homosexuality is a sin yet who cherishes their love. It is a virtue of Nauffts’ script and Hall’s staging that the deck is not stacked for either side. In fact, the show’s sole shortcoming is that the conflict is never credibly resolved.

For all the drama, Nauffts stuffs the play with laugh-out-loud humor resulting from snappy dialogue delivered by the droll Nesbit and the acerbic Wohl who have the fine-tuned timing of a V-8 engine. Yet the lines come out of their characters and don’t feel like jokes out of left field.

A popular leading lady under Hall’s tenure, Nesbit creates a quirky, lovable creature who has paid a long-term price for her excesses but still exudes a genuine love of simply being alive. While Nesbit disappears into the character, her acting technique is a marvel for fellow professionals to dissect.

This is Wahl’s best work since he played in Bent for Hall years ago. Often cast as a light comedian, Wahl is completely convincing as a deeply troubled man who would, in fact, benefit from the peace that Luke offers. When Wahl says to Luke near the end, ‘Why don’t you love me as much as you do Him?’ the actor fearlessly embraces Adam’s selfishness and yearning. While Adam is an annoyingly neurotic and self-destructive hypochondriac, Wahl injects him with a woebegone charm that keeps us from wanting to slap him upside the head.

Canfield pulls off a minor miracle in keeping Luke’s faith simple, sincere and credible. Even faced with Adam’s thinly veiled accusations of hypocrisy, Canfield’s gentle Luke doesn’t proselytize; he only yearns to share the precious gift he has found with the person he cherishes the most.

Especially impressive is Bateman who, with Nauffts’ help, never makes the homophobic racist father into a two-dimensional monster. Like Luke with his faith, Bateman’s bigotry is just who the man is, surprising absent any conscious malice. With Hall’s guidance, Bateman also expertly twists a word or a sentence fragment in speaking with Adam or Luke to indicate that he may unconsciously suspect his son’s sexuality but will never admit it to himself.

The gay component of Next Fall is a key facet that must have attracted Hall. He was a pioneer in putting serious gay-themed plays on a mainstream stage in South Florida: Bent, Gross Indecency: The Three Trials of Oscar Wilde and the controversial but still effective production of Love! Valour! Compassion!

A memorable moment occurs near the end of the play when the lovers are horsing around on a couch. There is nothing sensational about it; it’s just a scene of physical affection that is universally recognizable and therefore says more about the legitimacy of homosexual love than any words.

And at the end of the play, the mother hugs Adam. Most directors would have let the clinch go on perhaps two seconds. Hall lets the clutch linger for three or four times that long. You can feel the cleansing release of emotion from the two washing over the lip of the stage and into the audience.

Because in the end, that’s what the play is about: mutual compassion for each other’s mortality, frailty and nobility.

Next Fall plays through Mar. 27 at the Caldwell Theatre Company, 7901 N. Federal Highway, Boca Raton. Performances’ 8 p.m. Wednesday-Saturday, 2 p.m. Wednesday, Saturday and Sunday. Tickets $38-$50 available by calling (561) 241-7432 or toll-free (877) 245-7432 or caldwelltheatre.com.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design