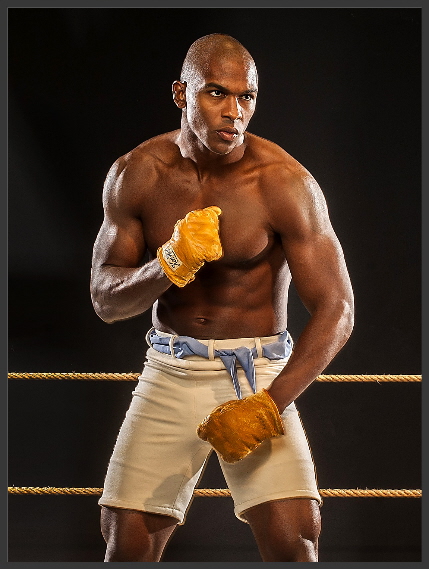

Aygemang Clay as Jay Jackson in GableStage’s production of Marco Ramirez’s The Royale / Photos by George Schiavone

By Bill Hirschman

Crack! There is a rare moment when a baseball connects so solidly with the bat that the jubilating crowd knows, just knows that the orb will go up, up and out of the ballpark, maybe into the next county.

Wrong sport, but that’s the sense that most audiences members will relish watching the superb GableStage production of The Royale — Miami native Marco Ramirez’s insightful pile-driving play about boxing, celebrity, racism, race relations and personal responsibility.

Powered —and that’s the precise word – by imaginatively theatrical staging, intensely fierce performances and Ramirez’s provocative script, The Royale scores as one of the best plays in the region this season. We saw the second-to-last performance of the production that bowed at Lincoln Center last spring and this edition is superior to that one in many respects.

Along with the 1969 Pulitzer-winner The Great White Hope, this marks the second fictionalized tale inspired by the real-life Jack Johnson who reveled in his celebrity as the first African American world heavy-weight boxing champion (1908-1915) . But Harold Sackler’s fine play simply recounted Johnson’s rise, flamboyant tenure and tragic fall as the racist world responded by crushing him outside the ring.

The Hialeah-born Ramirez, a successful TV scriptwriter best known here as a playwright for Broadsword at Mad Cat Theatre Company in 2009 and 2010, has far wider and deeper goals. His “Jay Jackson” is preparing for this first interracial title fight that has inflamed racism among whites while instilling intense pride among blacks.

What Ramirez excavates so well is the complexities, irreconcilable conflict and responsibility of dueling outcomes, each with profound costs to Jackson, African Americans and the country. Jackson wants the capstone of a long-sought personal achievement as well as the important social statement it would make, one that has an intense personal origin. But Ramirez depicts Jackson’s growing awareness that his likely victory will trigger mayhem and tragedies of racial strife. The loneliness of that decision and the inescapable personal responsibility for it emerge in the final third of the play as its real core theme.

This tightly-coiled production is so propulsively paced by Joseph Adler that it actually comes in about 15 minutes shorter than the New York production’s 80 minutes. But even when it slows down to breathe, Adler has elicited performances that arc with electricity.

As good as the script is and Adler’s work is, the headline is the performance of Aygemang Clay as Jackson. It seems almost impossible that this intense, nuanced creation marks Clay’s first professional stage performance. It’s not simply that this tall young man with a sculpted rippling body exudes some God-given magnetism. Molded by Adler, Clay is a force of nature throughout whether blithely tossing around Jackson’s confidence that borders on arrogance or issuing the bright broad grin manufactured by the media or the determined gaze of steel when he settles in to a challenge. Watch the real pleasure on Clay’s face and in his voice when he acknowledges to a young unusually talented opponent that for the first time in his career he felt truly challenged and therefore fulfilled. “For a minute, we were boxing,” he says, almost wistfully.

Throughout, Clay’s Jackson is voraciously hungry. For much of the play, we think it’s for prideful validation, but Ramirez’s protagonist has additional nobler goals. At the same time, the playwright reveals increasingly profound and conflicting stakes.

Adler’s work here is masterful. Certainly, he has been aided immeasurably by the movement/rhythm choreography of Rudi Goblen and the boxing coaching of Bert Rodriguez. But the overall pacing, the sense of a freight train blowing through a country crossing is Adler’s; the emotions flashing back and forth are his work. Nowhere is this more evident than in orchestrating the entire cast in the final match, which crescendos like a tidal wave.

The fight scenes, indeed much of the play, is driven by the fighters and the other characters clapping loudly in rhythm and stomping hard on the hollow floor boards like whipcracks. We rarely see anyone fighting face-to-face. Instead, the combatants face the audience as they box. But Goblen’s so precisely choreographs the movements that fighters realistically staggering back in perfect synchronization with an uppercut. Throughout these battles, the fighters emit a steady monologue of taunts to each other or inner thoughts, all realized by Ramirez and Adler as if it was a kind of music.

The entire cast has that vibe. Gregg Weiner, in his 15th GableStage show, creates an indelible force as Jackson’s white promoter/manager. His Max is a consummate huckster completely immersed in the economic American Dream, a pragmatic businessman who has hitched his career to a promising horse. With a clarion, razor-edged voice, Weiner’s Max also serves as a skilled barker exploiting this carnival called sport, but he is also intensely loyal to Jackson on a personal as well as economic level.

Shein Mompremier, another new face to most local audiences, smolders with various passions as Jackson’s sister who forces him to weigh the fallout will be if he wins. Although somewhat restrained in here first major scene, she becomes a fierce voice in Jackson’s head during the climatic fight.

We’ve been watching André Gainey in M Ensemble productions for 20 years and he has never been better than here as the grizzled loyal trainer who warns, “Lots of things bring a man down and they aren’t all in the ring.” Ryan George, who was in GableStage’s production of Tarell Alvin McCraney’s The Brothers Size, combines the necessary physicality with the ingenuousness of a young man just starting in his profession and who idolizes Jackson.

The version we saw at Lincoln Center was fine in its thrust stage at the floor level of a horseshoe auditorium. But, at least sitting in the center of GableStage’s intimate house, the play landed even more strongly. Lyle Baskin’s grey on grey set is a wooden-floored boxing ring surrounded and dwarfed by industrial girders, deftly lit by Jeff Quinn.

This is one of those don’t miss productions that vibrates and shimmers with the visceral energy and danger of a flurry of blurred fists.

Programming note: GableStage has reshuffled its next few shows. I’m Gonna Pray For You So Hard has been rescheduled for next season. In its place in the July 30 to August 28 slot will be Stalking the Bogeyman. That title had been slated for Oct. 1-30, but will be replaced by Hand to God, the recent Broadway black comic success about a troubled youngster whose hand puppet becomes an outlet for his darker side. (To read our review of that production, click here. ) Kicking off the new season will be An Act of God, Nov. 19-Dec. 18, a comedy narrated by, well, you know who.

The Royale runs through June 26 at GableStage, 1200 Anastasia Ave., Coral Gables, inside the Biltmore Hotel. Performances generally at 8 p.m. Thursday-Saturday, 2 p.m. and 7 p.m. Sunday. Runs 65 minutes with no intermission. Tickets are $45-$60 and students $15. For tickets and more information, call 305-445-1119 or visit GableStage.org

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design