By Bill Hirschman

The initial temptation is to rave about playwright Tarell Alvin McCraney’s alchemy of poetic, profane and prosaic language.

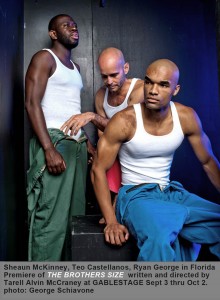

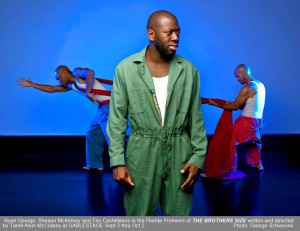

Or how the inventive production of his The Brothers Size at GableStage this month marks the first time his work has been professionally produced on his home turf. Or how it’s his first time directing his own work and we see his vision unfiltered through an interpreter’s eyes.

Or to celebrate what may be a watershed moment in a South Florida theater offering a mainstream audience the kind of work that employs highly stylized conventions to tell a story.

But, no, what should overwhelm anyone with a brother or sister is how McCraney depicts the conflicting/complementary synergy of sibling relationships as incisively as any play in the American canon.

That the brothers here are young black men trying to scrape a life out of the unforgiving underclass of a Louisiana bayou doesn’t erase a smidgen of easily recognizable universality.

Some theatergoers with taste, sophistication and intellect are not going to plug into this work. They’ll find it self-consciously arty. But just as many others with taste, sophistication and intellect will embrace it, rightfully so, as one of the high water marks of an atypically strong theatrical season.

McCraney, raised in Homestead, Liberty City and Coconut Grove, has quickly earned an international reputation as the young up-and-coming playwright who transmutes traditional theater into something to entice a younger, more diverse audience.

He blends contemporary settings and minority characters with West African folktales and classic epic themes without seeming forced or pretentious. Instead, McCraney relishes the collision of cultures. For instance, the names he chose for an auto mechanic, his ex-con brother and a canny street hustler are drawn from (and carry the traits of) archetypal deities in the Yoruban mythology founded in Nigeria and evolved in corners of South Florida.

Above all is his facility with words. McCraney’s vocabulary is the vernacular of the streets peppered with poetic imagery. But it’s woven into a remarkable verbal rhythm – sometimes measured and contemplative, often rapid-fire flowing wildly across the stage like a flooded river in Vermont. Sometimes it’s like hearing characters firing lines at each other like commandos shooting off automatic weapons in a video game.

The story is as simple as a ritualistic mystery play. Oshoosi Size(Ryan George) is a likable young man paroled “a minute ago” from a two-year stretch in prison. He is striving to re-establish his life in a downtrodden town on the edge of a Louisiana bayou by settling in with his older brother, Ogun (Sheaun McKinney) who has turned his skills at automotive repair into a modest business.

The problems of ex-cons struggling to cast off the consequence of their past sins are well-known. But McCraney and his cast invest them with flesh, specificity and voice.

The sudden appearance of Oshoosi’s ne’er-do-well cellmate Elegba (Teo Castellanos) upsets the fragile balance with his seductive appeal to abandon Ogun’s hope that Oshoosi will lead a straight life.

The play is the second of three involving related characters. Ogun’s monologue here about a lost love refers to the plot of the first play, In the Red and Brown Water. Elegba’s son is the focus of the third play, Marcus: Or The Secret of Sweet.

Running under The Brothers Size’s expected plot arc is that insightful portrait of two brothers working in tandem through the baggage of their past and their hope-against-hope dreams for some kind of future.

Among several achievements as actors, George and McKinney create that sense of people bound by past joys and betrayals, and who feel that brings a debt of responsibility even when one or both let the other down. McCraney paints a portrait of how relationships bind people both the positive and negative definitions of the word.

One memorable scene has the brothers playfully singing together to Otis Redding’s rendition of “Try A Little Tenderness” on the radio. You instantly sense the joyful sense of do-you-remember when we used to do this and if you do then our shared past has the worth and strength to help us persist and prevail.

Yet, a few scenes earlier, Oshoosi explodes in frustration that Ogun’s efforts to guide and protect him are as constricting as prison.

In theory, the play is set on a bayou. But McCraney stages it in a bare black box with a cyclorama behind a scrim for dream tableaus. His script does little to illustrate a specific sense of place; his staging makes it clear that it is no accident. People talk a little about the environment, but the director’s choice of this most generic of settings underscores how the themes transcend time and place. With such a spare set, Jeff Quinn’s nimble morphs of lightscapes carry much of the heavy lifting in creating shifts of time, place and mood.

black box with a cyclorama behind a scrim for dream tableaus. His script does little to illustrate a specific sense of place; his staging makes it clear that it is no accident. People talk a little about the environment, but the director’s choice of this most generic of settings underscores how the themes transcend time and place. With such a spare set, Jeff Quinn’s nimble morphs of lightscapes carry much of the heavy lifting in creating shifts of time, place and mood.

It’s all emblematic. McCraney revels in the sheer theatricality of theater, the use of artifice to communicate thoughts, ideas and emotions unhindered by the naturalism that dominates most work in South Florida.

It’s most notable when the characters frequently speak aloud the parenthetical stage directions such as “Ogun exits” or inserting an adverb smack in the middle of a speech to indicate how the line should be said.

Having read In the Red and Blue Water, trust us that this doesn’t work very well on paper. But in performance, it is a brilliant conceit. The stage directions are like Shakespearean asides woven into the rhythm of the speeches and the interplay of dialogue. It requires the actors to make quicksilver changes in attitude from angst-choked declamations to wry asides to the audience and back again in a space of a few seconds. This cast – especially George— spin effortlessly on these emotional pivots.

The technique is Brechtian in its reminder that we are watching unreality. We’d even argue that the interjections are not a wise choice in the most passionate scenes; they break the audience’s unconscious buy-in to the heart-rending emotions. You can make an intellectual argument to support that artistic choice, but it’s not a satisfying one for the audience.

McCraney the director capably places the actors to emphasize their interaction and occasional solitariness. His pacing is admirable from introspective musings to the verbal equivalent of door-slamming farce.

Another hallmark is his marriage of the sinuous music of his words to the athletic grace of his characters’ movements. McCraney has readily acknowledged the ever-changing body language as the influence of childhood hero Alvin Ailey and Castellanos, his first mentor whose own performance art is movement-based.

McCraney is blessed with a cast perfectly in tune with the work. They inject the 70-minute play with an infectious energy and dexterity that resembles the teamwork of a major league infield. All three mischievously recreate a run-in with an abusive lawman like storytellers around a campfire. It’s almost a vaudeville turn with a slight flavor of irreverent minstrelsy. McCraney’s directing this edition likely contributed to the actors’ preternaturally fluid delivery.

Story-telling is a key to McCraney in general but also for these characters who each hold the stage by themselves for long passages in which they resurrect the past: Oshoosi recalling the hell of incarceration, Elegba relating how his friend mourned in prison for the lost relationship with his brother, Ogun reviving his feeling unjustly held responsible for Oshoosi’s irresponsibility throughout their lives.

The actors’ fearless excavation of their personal emotional core and their willingness to toss their entrails on stage for others to see is a master class lesson for certain local actors whose directors don’t demand they dig inside themselves for a truthful performance. All three excel especially at communicating yearning for dreams they can hardly articulate.

Castellanos’s wiry dance-trained bantam body is infinitely articulate even when his words slur. The tall imposing McKinney (good to have you home from L.A. no matter how briefly) initially seems stolid but peels away protective armor to reveal the festering anguish seething underneath. First among equals is George who communicates a life cauterized by incarceration. His scene in which he burbles with enthusiasm about unrealistic plans for the future, albeit fueled by a few tokes of weed, will shatter the heart.

There’s really only one serious misstep all evening. The play begins with the house lights up with the actors entering in a formal procession, beating a paint can for a drum and ringing the bell-like “singing bowl” like a group of Buddhist monks en route through town before entering the temple for prayers.

After perfectly setting the feel of a ritualistic invocation, the mood is shattered by inserting the customary welcome from Producing Artistic Director Joseph Adler. That should be done before the ritual begins.

Theatergoers owe Adler a deep debt of gratitude for persevering two years to get McCraney to come work here and for modestly acknowledging that the piece needed a director with a different sensibility than his own.

Of course, this is hardly the first time a local theater has presented a stylized theatrical work that requires the audience actively invest their imaginations rather than sit passively back like a crowd in a multiplex. Small companies like Mad Cat Theatre, Castellanos’ own company D-Projects and PlayGround Theatre (all in Miami-Dade) do it frequently, but they play to tiny sophisticated clienteles and children. This season, the Arsht Center in Miami imported the House Theatre of Chicago’s Wicked-meets-Carrie tale, The Sparrow, noted for exactly that kind of staging.

It’s not even GableStage’s first foray into unexplored territory. Adler’s heroic stagings of Blasted and The Adding Machine took the drama and the musical to places most local audiences had heard of third-hand but didn’t realize could feel theatrically fulfilling.

But something about this production of The Brothers Size, perhaps its accessibility and universality, seems primed to gently lead The Audience across an invisible artistic line in the dirt.

We hope and recommend they let McCraney take their hand.

For an earlier story about McCraney and this play, see this link.

For WPBT’s uVu photojournalist Neal Hecker interviewed McCraney recently on video. The interview is broken down into six parts of 2 to 4 minutes each.

Links: Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5 Part 6

The Brothers Size runs through Oct. 2 at GableStage, at the Biltmore Hotel, 1200 Anastasia Avenue, Coral Gables. Performances are 8 p.m. Thursday-Saturday, 2 & 7 p.m. Sunday. Tickets are $37.50 to $47.50. Call (305) 445-1119 or visit www.gablestage.org

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design

One Response to Tarell Alvin McCraney and GableStage Deliver Memorable The Brothers Size