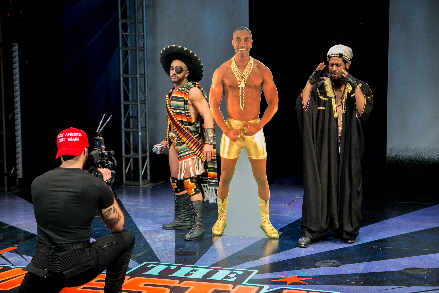

Garrett Turner strutting his stuff as the title character in The Elaborate Entrance of Chad Deity from Miami New Drama and Asolo Repertory Theatre / Photos by Stian Roenning

By Bill Hirschman

A personalized perspective on the phenomenon that is The Elaborate Entrance of Chad Deity:

I first read the script by Kristoffer Diaz shortly after its bow in Chicago in 2009. It seemed on paper a startlingly original and promising exercise in satiric social commentary, but I couldn’t quite visualize this show, which alternates scenes of grappling costumed wrestlers with impassioned speeches about racist stereotyping.

Then I saw the finalist for the Pulitzer Prize at the Second Stage in New York and understood its use of the bogus world of professional wrestling as a metaphor for the shallowness and hollowness of some vaunted American values.

Finally, I caught Clive Cholerton’s triumphant multi-media production at the Caldwell Theatre in 2012 in which his troupe nailed Diaz’s savage indictment of 21st Century American society amid copious comedy. The fact that it fatally drove away the Caldwell’s subscription audience said more about their shortcomings than the production’s superlative qualities.

But although a fan of its raucous irreverence, I was unprepared how the current co-production of Miami New Drama and the Asolo Repertory Theatre Company resonates so deafeningly with the current zeitgeist that it seemed to have been written last month. Diaz’s prescient observations are even more relevant, even more accurate than they were nearly a decade ago.

Chad Deity intersects themes of immigration, racism, xenophobia, nativism, assimilation, the shallowness of show business and the blunt inhumanity of capitalism. It depicts minorities trying to slice out a piece of the American Dream when a segment of the citizenry doesn’t believe they are, could be or should be a part of that success. It exposes how other people coldly manipulate Everyman’s desire for the Dream and the genuine American Spirit to promote a soulless self-centered accumulation of money and power – a venality that goes beyond hypocrisy because they acknowledge no worth in the verities they are exploiting.

This has been in the script all along, but the context of the past two years amps up the wattage, driving the themes in our face until it’s like we’re looking into a carbon arc searchlight.

But Diaz’s real genius is enlisting the audience’s interactive participation in the spectacle, even after exposing its fraudulence. That implies all of us being, at its most generous, enablers, and at worst, participants, in the shameful charade. Indeed, the real pain is watching minorities so hungry for a modest piece of the American Dream that they are willing to sell out their cultural pride for a chance to be a part of it.

These themes are constantly turned inside out and backwards, mixed and matched, until Diaz has eviscerated the dark marrow of the American Dream in the 21st Century.

And by the way, the play is hilariously funny and hugely entertaining as we get an insider’s view of the blithe deception of “pro” wrestling.

Our tour guide is Macedonio Guerra, a lively if compact man performing under the name The Mace. Genial, animated and highly articulate with a lacerating wit, Mace explains he is of Puerto Rican descent born in the Bronx. Mace explains that he grew up worshiping the spectacle of the second-tier professional wrestling circuit and especially the good-versus-evil stories of the silly make-believe world.

Mace is proud of having achieved his childhood dream to have become a highly skilled athlete in “THE Wrestling” league – skills necessary to avoid getting hurt despite the complete sham. In long wry speeches to the audience, the pragmatic kid from streets displays an incisive intelligence and perceptiveness about the occupation and its shortcomings. For instance, he tells us, the secret of “professional” wrestling is that it’s the losing villain who has to be an expert. He executes moves dangerous to himself to make the “star” look good. Mace doesn’t mind this, it’s part of the deal.

Mace enthuses like someone who had been always told that his dreams must be deferred: “It’s a daydream job. And I’m happy to lose. And I’m happy for the audience to tell me that I suck. Because when I wake up in the morning, I don’t even need an alarm clock. And I don’t mind that my knees hurt. My hands hurt. My everything hurts. I don’t mind. Because I’m one of THE Wrestlers. And I am in love with who I am.”

He notes that he and the winning wrestler have to cooperatively choreograph this hypocritical fantasy: “That fact is powerful and beautiful and, like I said, one of the most profound expressions of the ideals of this nation.”

In these bouts, the “hero” is the titular Chad Deity, a charismatic, preening bling-addicted blowhard with a sculpted body, an America First mantra and an outsized gangsta persona – but who privately admits cheerfully that he is a lousy wrestler. He is both incredibly full of himself and astute in the realities of the larger game being played.

Frustrated at the inequity, Mace stumbles upon a possible path to fame and fortune. He teams up with Vigneshwar “VJ” Paduar, a Brooklyn-born Indian-American streetwise basketball athlete and ladies man just as flamboyant as Chad.

League owner Everett K. Olson may be a know-nothing jerk, but he insightfully perceives and exploits the fears of fans afraid of change, afraid of newcomers, afraid of losing their standing, looking to blame someone for their own failures.

VJ and Mace fashion a tag team of villains for Chad that racists can hate: a fundamentalist Muslim and an illegal alien from Mexico. Not only they are pretending to be of other nationalities, but they are furthering the toxic stereotypes infecting society. But they want success so badly that they play along as the scenarios get more and more outrageous. For a while.

Even with two acts, this show races along due in part to the endlessly inventive direction of New York-based Jen Wineman, the peerless performances from the dynamic actors and one other secret that accounts for the incredibly fluidity of the evening: This specific production (including lighting, sets, sound and costumes) was mounted at the famed Asolo in Sarasota in April after seven weeks of rehearsal including two weeks just on the fight choreography. Seven. Then with the same director and the same three actors playing the leads, before this run they had another four weeks in Miami. Four. The vast majority of South Florida rehearsals are about two weeks plus a day or two if the cast is lucky.

The production seeks, nay demands, audience participation of cheering, whooping, hooting, booing and waving paper masks with Chad’s face emblazoned on them. Indeed, we sat next to a company ringer brought in to surreptitiously to ratchet up the tumult.

The physical elements had to be adapted to the Colony Theatre stage and the cast now includes a local actor in the crucial role of Olson. But the leads know the piece inside out and backwards.

It pays off. These actors easily inhabit these people proud of their hard-won skill at legitimizing (and monetizing) unreality.

Pierre-Jean Gonzalez wins over the audience seconds after his appearance as Mace, filled with joy and pride at his modest accomplishments. Over the evening, the actor subtly but clearly indicates how Mace becomes disillusioned and increasing angry over the scenario’s ever devolving descent into validating racist stereotypes.

Garrett Turner simply becomes the tall Apollo in love with himself, who savors the rewards of a game he knows is rigged in his favor and who feels not the slightest bit guilty for taking advantage of the cupidity of passive bigotry.

Raji Ahsan as “V.J.” is flawless as the ultimate assimilated minority who wallows in American pop culture but whose seeming assuredness is shattered by the naked immorality of this world.

The ringer is local favorite Carbonell-winning Todd Allen Durkin as the cluelessly amoral Olson. The puffed up Durkin, who seems to be strutting even when he is seated, has an abrasive electric sander voice that sounds like Jackie Gleason puffing on a stogie. Durkin has spent less time on stage in recent years, working in locally-based television series and serving as personality on the FM station The Beach. But it takes him about three dismissive snorts to firmly establish this character. His Olson is so certain of his ability to predict the lowest common denominator taste of the public that he is blithely ignorant that his morality is reprehensible.

Filling out the cast is Jamin Olivencia as various opponents and Gabriel Bonilla as the live cameraman.

Wineman has the physical staging displayed with a smoothness that its virtually invisible. Of course, a nod is due the fight choreography from Michael Rossmy.

Any production of this play requires an immense investment of time, money, skill and imagination to persuasively recreate the loud, circus-like world of blaring noise, blinding floodlights, air drops of fake currency, multi-colored spangled confetti, vivid projections and a score of wickedly funny videos (live and pre-recorded) splashed across seven screens in the auditorium and coordinated down to a split-second by stage managers and a tech crew. In every department, this production scores A-plus and look for these crew members’ names when Carbonell nominations come out a year from now.

Diaz’s script is not simply witty and perceptive. Although peppered with locker room language and offensive racial slurs, the dialogue and especially Mace’s speeches to the audience have that love of word play. One of his inspired running bits is to have Mace tell the audience that there is no way such and such ploy will fly, only to find in the next cutaway scene that there is no bottom to what heresies that Olson and the wrestling audience will embrace.

He has Mace say, “When I’m on the attack in a wrestling match, it’s a constant process of action, reaction, and evaluation, thinking about the outcome of the match, which yes, we already know going into the night, so don’t dismiss my art form on the basis of it being predetermined unless you’re ready to dismiss ballet for the swan already knowing it’s gonna end up dead.”

This merciless razor-sharp lampoon is a rabbit punch at the solar plexus of society in 2018.

The Elaborate Entrance of Chad Deity from Miami New Drama and the Asolo Repertory Theatre plays through Feb. 18 at the Colony Theatre, 1040 Lincoln Road, Miami Beach. Shows 8 p.m. Thursday-Saturday, 3 p.m. Sundays. Running time 2 hours with one intermission. Tickets $30-$59. Visit miaminewdrama.org or https://www.colonymb.org/ourtown.

Pierre-Jean Gonzalez and Raji Ahsan flank a photo of Garrett Turner as they play racist stereotypes in The Elaborate Entrance of Chad Deity

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design