Sean McClelland's artist rendering of his set for "August: Osage County."

In less than two months, a small cadre of craftsmen has designed and built a three-story house in Coral Gables complete with a study, a wraparound porch, a dining room and a bedroom in an attic that looms 40 feet over a visitor’s head. (In reality, the edifice is only half a house, as if a tornado had scraped away an exterior wall.)

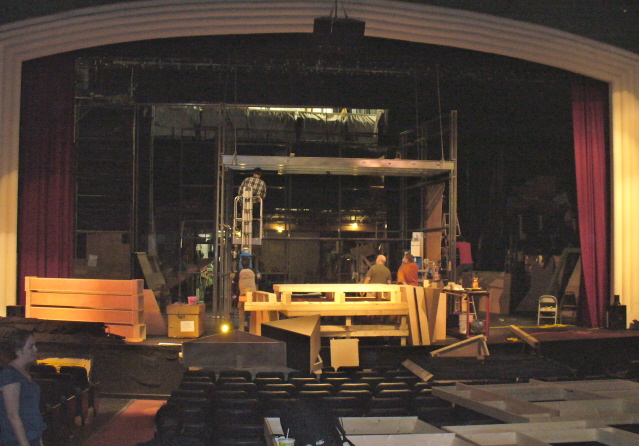

The massive structure of wood and steel has not been constructed on a vacant lot, but inside the proscenium arch of Actors’ Playhouse on the Miracle Mile.

The century-old manse that envelops the fictional Weston clan is the 14th character in Tracy Letts’ Pulitzer-Prize winning epic of family dysfunction, August: Osage County, which opens Friday.

It also represents one of the largest sets that Actors’ staff has ever built. It blots out the space inside the 46-by-21-foot proscenium. The porch juts out to the edge of the stage. Skeletal roof timbers scrape the top of the stage and seem to thrust out over the audience.

A few musicals’ sets at Actors have been marginally larger. But the scope of it ‘ uncounted yards of lumber and 1,000 pounds of steel to fabricate this vast a building — which performers will run up and down for three and a half hours every night — has been a huge challenge.

‘The easy part is, at least, it doesn’t move,’ said designer Sean McClelland.

Seven weeks from opening night

Occupied with several assignments this fall, McClelland doesn’t begin seriously working on the design until mid-January when he meets with director David Arisco to discuss the script. Worse, the auditorium is booked with shows and other programs back to back. The entire team will be racing against the unalterable deadline of opening night.

When he and Arisco are in general agreement, McClelland sits with his sketch book. He is hemmed in somewhat because Letts detailed the look and layout of the house in the script. McClelland especially wants to avoid mirroring the set created by Todd Rosenthal for the Steppenwolf debut and the New York run.

He starts brainstorming with one eye on creating a physical metaphor for the play and the other on how practical it will be to build.

‘I based all my research on houses from the Midwest’.Sometimes it’s an artist or image or emotion that inspires. This time, however, it came from just sketching away. I had an idea early on to lose the house altogether and show it all in a flat picture frame montage like the ones you buy at Target that hang on the wall.’

Instead, he decides on a three-dimensional approach. ‘I am giving the house a very heavy base that peels away on the edges, showing past layers of paint, to plaster, raw wood paneling and beams, to nothingness of black, an ‘if these walls could talk’ approach.’

He sees the house as a metaphor for the matriarch Violet whose drug-induced dementia leads her to viciously lambaste her family. The savaged walls mirror the familial scars revealed when she rips into her family.

Cutdown half-walls ‘also solve some design issues of sightlines, lighting angles and (provide) a more interesting visual aesthetic. A big pet peeve of mine is a broken-away squiggly wall for no other reason except to see through it, when it doesn’t fit with the rest of the design.’ Here, he says, it clearly does fit.

Set design is always in flux, marked by perpetual fine-tuning until the first performance. Like a participant in a complex dance with multiple partners, the scenic designer must consult and collaborate with the director, the technical director, the lighting designer, the sound designer and the actors among others.

For instance, McClelland wants to move the entire set close to the audience and enfold them in the environment. As a result, the team has to determine how to stage and light scenes in the attic so they are visible to the audience in the front rows who might only see the underside of the attic floor.

Theater ‘is the last place in the world where people actually collaborate,’ says Gene Seyffer, the technical director who turns McClelland’s ideas on paper into something made of planks, girders, nails and welds.

The physical limitations of the stage means that while the house seems to have the three stories required by Letts, it really only has two and half, like a split-level home with a shortened staircase.

McClelland also designs subtle visual tricks that the audience will never notice including skewing the side walls an extra five degrees wider. That will make the house seem deeper and add to the audience’s sense of being embraced (or smothered) by the house. Construction-wise, that’s not a major problem when a set is mostly made of wood. But this one requires a steel substructure; building steel frames with anything other than a 90-degree angle adds a major headache.

All this goes into McClelland’s art rendering that looks fanciful but is carefully created to be feasible to build on stage.

Time is the enemy, but McClelland is used to it. At 33, the tall Pittsburgh native has designed and built dozens of sets at the University of Florida, Actor’s Playhouse, Mosaic Theatre, Palm Beach Dramaworks, the now-defunct Seaside Music Theater in Daytona Beach and Flatrock Playhouse in North Carolina.

It helps that he’s working with Seyffer, a veteran designer himself whose career reaches back to the last works of the legendary Jo Mielziner. They confer so regularly that they finish each other’s sentences.

McClelland starts, ‘I go to Gene and ask him if we can do this’.’

Seyffer finishes, ”and I get back to him whether we can.’

Five weeks from opening night

Seyffer turns McClelland’s sketches into detailed floor plans and elevations using a computer-assisted drafting program.

In a scene shop 12 miles north on I-95, the team begins constructing pieces of the house. Seyffer’s chief assistant, Hector Ferrera, leads an ad hoc crew that will vary between four and 10 workmen with varied areas of expertise.

Normally, the majority of a set is built in the scene shop in large sections that fit through the downtown theater’s 7-by 9-foot loading door. Then they are slipped together relatively quickly on stage.

But the size, scope and weight of this set and the large amount of structural steel means the crew can only cobble smaller sections in the scene shop.

Every hour counts. A pile of porch columns made of plywood are rectangular. But if the production had the time and money, they’d be circular, McClelland says.

Two weeks before opening night

Photo: Bill Hirschman

The pieces have been trucked into the theater. Wooden sections of wall are spread out on top of the rows of seats in the auditorium as the crew begins building the metal superstructure that will house the living room, staircase and attic. The air is filled with the rip of saws and the whine of electric screwdrivers.

Most crew members have other jobs and are called in just for the few weeks. But they aren’t simply human tools. ‘We can’t hire people,”’ Seyffer motions to his neck, ‘just for what they have from here down’ because the process is an unending parade of spotting problems before they occur, altering plans and developing solutions on the fly.

The silhouette of the house grows as the clock starts limiting options to deal with unexpected setbacks.

‘ We usually go with the first solution we think of. If there was time, we’d look into others. So what we come up with may not be the cheapest (solution) or the best, but it’s the fastest,’ Seyffer said.

Despite the time pressure, the crew is always conscious that the structure will get a merciless workout from a dozen people climbing over it for a month.

‘It can’t just look good; it has to be safe,”Seyffer said. But just as important, ‘it has to feel safe for the actors. It can be safe and still have some spring in the floor,’ which unnerves the cast members. ‘The actors don’t need to be thinking about anything else.’

A week and a half later, the crew is racing to get the set in shape for the actors’ technical rehearsals called 10 of 12s ‘ ten hours of work spread over 12 hours. Although walls aren’t painted (some are even missing), the rehearsal demands that every door, every floor, the stairs, everything the actors will work with must be in place and operational.

Five days before opening night

Photo: Bill Hirschman

The structure may look a lot more like a home with all the walls in place and some sections wallpapered. But the truth is visible: Large sections of the set still need finishing. There’s a steady soundtrack of hammering and the smell of fresh-hewn sawdust wafts over the auditorium.

The key furniture and a few props like a bottle of Jim Beam are in place, but hardly everything. For instance, the script calls for the house to be awash in books, so the staff has just sent out for a small library of volumes. The to-do list includes unpacking Styrofoam molding made in Pompano Beach and attaching it to walls.

And a preview audience is due at 8 p.m. Wednesday — two days and eight hours from now.

‘We’ll probably go back in Thursday to finish it.’ Seyffer says the meaning of the word ‘done’ shifts around a lot.

Money is always in the back of their minds just like time. The standing joke among scenic designers is that theaters always spend more on the costumes than the set. In this case, $35,000 was budgeted for the set, but the final total seems to be coming in just under $33,000.

Seyffer points to a china cabinet that covers part of a wall. ‘The audience doesn’t know that the baseboard ends right there and there’s no paint or wallpaper behind it. Every penny I spend, I want the audience to see.’

Three days to opening night—the night before the first preview

There’s still more to do. But the work now has to be scheduled before and after the cast rehearses. As a result, McClelland, Seyffer and company expects to be working into early Wednesday morning, maybe even pull an all-nighter or two this week.

Indeed, McClelland responds to an email at 2 a.m. Thursday: ‘As they say, if we never opened the show the set wouldn’t ever get done.”

Despite the tension of the final push, Seyffer is confident that the physical reality of McClelland’s vision will be ready. The opening-night crowd may be amazed by the tableau when they walk in Friday night, but they won’t know the sweat invested in it.

Seyffer says, ‘Whatever struggles we go through, in the end the magic should seem effortless to the audience.’

Curtain Call

Even as they put the finishing touches on the Weston home, even before the first round of applause, the tech crew is preparing a set for the spoofy spy thriller, The 39 Steps, opening in the second floor theater on May 11.

Much of the scenery is being rented, but it’s designed for a large proscenium stage like the downstairs auditorium. So it has to be cut down to fit the half-size house upstairs which is only as tall as an elementary school stage. Plus, the pieces have to be hauled up a long staircase and maneuvered around tight corners.

At the same time, the crew still has to finish ‘dressing’ the August: Osage County set with props and fixing doors that stick or screws that have come loose.

They know it’s all temporary. If the show closes on schedule, the walls of the venerable homestead will start to fall April 4. Demolition will take two days.

Unlike Broadway productions, which scrap all their sets, local companies cannibalize the wood and steel where possible to save money on future sets.

‘See that red piece of steel up there?’ Seyffer says. ‘I’ve used that so many times, it probably could get its own union card.’

August: Osage County plays through April 3 at the Actors’ Playhouse at the Miracle Theatre, 280 Miracle Mile, Coral Gables. Performances 8 p.m. Wednesday-Saturday, 2 p.m. Sunday. Tickets $40-48. Visit actorsplayhouse.org or call 305-441-4181.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design