By Bill Hirschman

By Bill Hirschman

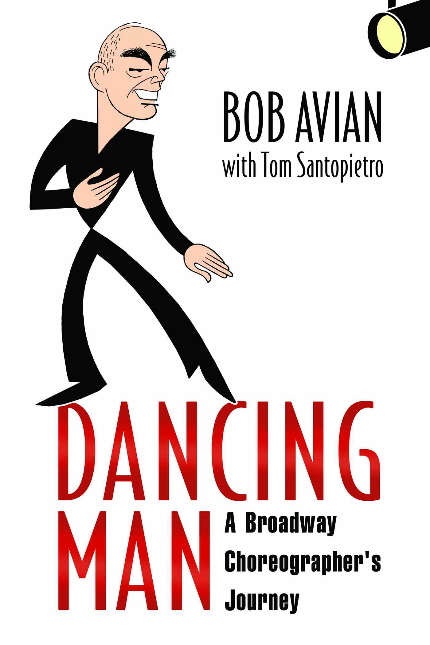

Dancing Man, A Broadway Choreographer’s Journey, by Bob Avian with Tom Santopietro, University Press of Mississippi, 207 pages

Theater, more than perhaps any other genre, is a co-creative art.

Civilians and even critics may laud a high-profile charismatic member of the team, even justifiably recognizing their genius. But few theater insiders buy into an image akin to a film auteur. Often someone is more powerful than others, more influential. But in most cases, as theater pros will tell you, what appears opening night, good or bad, is the result of collaboration that defies assigning any moment or idea to a single artist.

This paradigm is repeatedly depicted in Bob Avian’s autobiography Dancing Man, an engrossing account of the creation of theater seen from the inside in an illuminating tale told with the fair clear-eyed vision of someone who loves the art and the artists but who rejects wearing rose-colored glasses.

Few are in a better position than Avian. His six-decade Tony-honored career as a chorus member, choreographer, co-choreographer, director and producer of iconic Broadway musicals has directly involved him in Company, Follies, Dreamgirls and what will likely be in the first paragraph of his obituary, A Chorus Line.

Although Avian has helmed numerous other productions on his own, such as Miss Saigon, theater aficionados will notice all four of those aforementioned triumphs are better known as being directed and/or choreographed by the legendary Michael Bennett.

Which is the point.

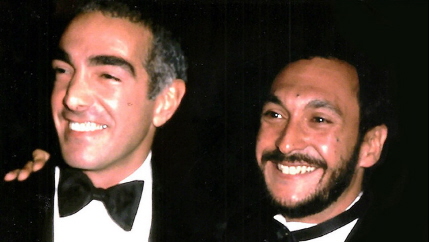

The late Bennett himself, arguably Avian’s best friend, would volunteer that the two were creative partners with differing temperaments and skill sets that merged together to form a whole.

Avian, who credits others as well at every opportunity, was co-responsible for many of the memorable images and moments in musical theater history that outsiders credit solely to Bennett.

The opening audition number in A Chorus Line, “One,” in which about half the hopefuls are cut, was assigned to Avian by Bennett. Avian with cast members Donna McKechnie, Baayork Lee and Wayne Cilento put it together in a half-hour.

The well-documented groundbreaking development process was well underway but still a bit unfocused when Avian suggested that the overarching frame in which the stories ought to be told could be an audition.

But the tone of Avian’s book, co-written with Tom Santopietro, never ever says, “Look at what I did. Give me credit, too.” There is no ego here, no attempt to downplay Bennett’s once-in-a-lifetime genius, merely a simple statement of facts.

But the tone of Avian’s book, co-written with Tom Santopietro, never ever says, “Look at what I did. Give me credit, too.” There is no ego here, no attempt to downplay Bennett’s once-in-a-lifetime genius, merely a simple statement of facts.

So he spotlights the moment when Bennett was talking to set designer Robin Wagner about possible configurations for a budding musical about dancers when Bennett simply took a piece of chalk, drew it across the stage and said, “That’s the set.”

What unreels is an unparalleled view of the intricate construction of new Broadway musicals. Some stories have been told before, others not. But it is a treat both for lovers of backstage Broadway lore and instructive to outsiders.

For instance, the high profile Cassie did not get hired at the finale when A Chorus Line initially went into preview performances until actress Marsha Mason (who they met when directing Neil Simon’s The Good Doctor) said the show needed Cassie to be hired to provide satisfying closure.

The book opens not with a chapter on A Chorus Line but a how-your-sausage-is-made account of Coco, the 1969 Andre Previn-Alan Jay Lerner musical starring the lead actress who could not sing or dance, Katharine Hepburn. The details of how he, Bennett and others dealt with this challenge is an education – efforts that led to an eight-month run of what Avian terms a “smash-flop.”

Of course, there is a chapter on A Chorus Line, another on Company, another on Follies. But also one on the hard, detailed work trying to salvage Seesaw and Ballroom, another about guiding the mercurial, insecure Jennifer Holliday in Dreamgirls to create a legendary performance manufactured from blood and sweat.

He talks about his trifecta when there were posters simultaneously in London of his solo projects Miss Saigon, Martin Guerre and Sunset Boulevard, which had as much drama offstage as on.

Along the way, he has worked with a veritable who’s who of Broadway legends (the book leads off with a list of “Leading Ladies”) and he often discusses them as people and performers with respect and admiration but also a workman’s assessment of their strengths and limitations. The book is not gossipy but revealing.

Recalling his stint in the chorus of Funny Girl, he writes, “It was fascinating to be on stage with Barbra, or even just to watch her from the wings. She was not warm and cuddly, but the company adored her and was protective of her.”

Of Holliday, he writes, “Jennifer was always on the verge of being difficult; it seemed to be a form of self-protection for her, and I was constantly building her up, hoping to encourage her. Her talent was so deep and so extraordinary that I felt this show could make her a true star.”

Also threaded lightly through the book with the same matter of fact aplomb is recounting life as an openly gay man over the past 60 years, including living through the scourge of AIDS.

But simply because of their personal closeness and their professional proximity, Bennett is a major figure through much of the book. Their relationship emerges as loving although they weren’t lovers, more like brothers. They fit together in temperament artistically as well. For instance, Bennett was more jazz oriented, Avian ballet. Avian was the peacemaker after Bennett upended a rehearsal.

As is well known, Bennett’s lifestyle spun out of control and he died of AIDS-related lymphoma. While Avian admits to his own ambition and substance use, he quietly observes with love that “As to that tremendous success, (Bennett) sometimes handled it well but at other times succumbed to drugs, alcohol, and the bouts of paranoia that affected all of us. He was looking to escape the pressures and have fun, and I plead guilty to some of the same charges; Michael, however, flew particularly high and too close to the sun.”

Avian lives part of the year in a seaside condo in Fort Lauderdale with his husband Peter Pileski and they attend some local productions where he is an unfailingly genial friendly presence.

An example: After I interviewed him several years ago, I ran into him during the intermission of a mediocre local production (to be kind) of a show that he had forged a special connection with years earlier. Before people with the show approached him, we exchanged looks across the lobby. He was clearly in artistic pain. But as soon as someone recognized him and came up to ask his reaction, his visage changed and he could not have been more gracious.

Amid his stories of working with Andrew Lloyd Webber, Hal Prince, Patti LuPone, Cameron Mackintosh, Carol Burnett, Donna McKechnie and on and on, Avian is pleasant storytelling company, someone you’d love to have a glass of wine with some evening and listen as he gives you the best seat in the house in a journey across much of musical theater of the past 60 years.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design