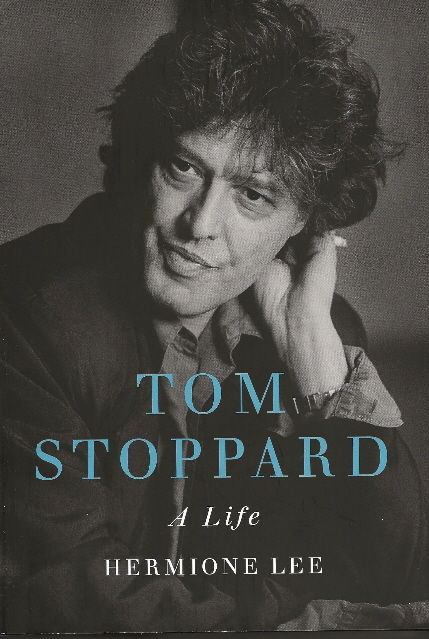

Tom Stoppard: A Life, by Hermoine Lee. Knopf. 24 pages of photos. 872 pages. $35 ISBN 978-0-451-49322-4. Available Feb. 23

By Bill Hirschman

Most biographies factually mirror the life and times of their subject in a chronological narrative. But few mirror the complexity and structure of the subject’s own work with the stunning faithfulness of Hermione Lee’s exhaustive and exhausting epic examination of one of the greatest playwrights in English or any other language, Tom Stoppard: A Life.

This 872-page volume, seemingly as weighty as the Oxford English Dictionary, invests a staggering amount of research to limn a portrait of the legendary author of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, Arcadia, Jumpers, Travesties, The Real Thing, The Coast of Utopia, not to mention screenplays for Shakespeare In Love and The Russia House, plus scores of radio and television plays, plus magazine articles, plus elegies, plus, plus…..

Theoretically, to even open this book, you have to be more than “aware” of Stoppard whose partial resume also includes newspaper reporter, columnist, essayist, reinterpreting adapter of foreign language classics, social activist, pop culture aficionado and sports fan.

All his literary efforts, but especially his plays, are suffused with a depth and intricacy of intelligence that embraces dazzling wordplay, advanced mathematics, conflicts in political and social philosophies, wry comedy and – contrary to some early assessments—intense if subsumed passion.

The tome by one of the most acclaimed biographers in England has three major thrusts simultaneously and inextricably woven together.

One, of course, is tracking of the arc of a life, albeit in incredible detail that gives a texture even most of the most ambitious biographies lack. Every time he moves to a new house, she describes its exterior, interior and furnishings for several sentences. Indeed, this is not simply a Wikipedia recitation of dates and events; she places his ever-morphing personal journey inside the historical, political, social and philosophical context in which they occurred and specify how they later influenced his work.

Second, as we follow his evolution as a person and an artist travelling through the 20th and 21st centuries, she creates an almost independent travelogue depicting the social, political, cultural and philosophical environment of those times. His life travels alongside seismic changes in the world on so many fronts, almost all of which are discussed here, not just as a backdrop but, again, as elements that he incorporated in his work.

Third, she recounts with insight as well as, yes again, detail all the influences, inspirations and development of every major and most minor works in his prolific oeuvre. She examines every significant character, every plot development and especially investigates their meaning as she twirls his themes around like syrup in a melting ice cream sundae. Coming from an esteemed emeritus professor of English literature at Oxford University, this is invaluable advance homework for anyone planning to see, act in or stage any of his famously dense flash flood of ideas, factoids, philosophies, characters and emotions.

Sometimes it’s all a bit much; you really have to want to know every cranny of what makes and made an artist bordering on genius to circumnavigate this globe. Dame Lee, honored for her biographies of Virginia Woolf and Edith Wharton, is a no excuses, straight-forward writer who gifts you with few self-aggrandizing flourishes. Instead, she depends on the vibrance of her subject and the interest of the reader to carry a visitor through this lengthy odyssey.

But what a subject. Born in Czechoslovakia to a perfunctorily Jewish family, he moved to Singapore when the Nazis came to power, evacuated to India, and finally settled with his mother in England – where he immediately and irrevocably assimilated and forever claimed as home. While he did not feel especially connected to his family’s religious roots or national origin (he didn’t even know his parents were Jewish until 1993), his indifference would fade over time, in part as he belatedly researched his forebears and discovered most died in the Holocaust.

Stoppard started as a reporter-columnist then fell into theater reviews, then cultural criticism. All reflected a trenchant wry wit that could not disguise his inherently incisive analytic mind. Over time, he both wrote about and interacted with scores of names either established or destined to be in the literary and theater pantheon. During his life, he was a colleague, mentor, acolyte or fan of everyone from Pinter to Beckett, from Peter O’Toole to Mick Jagger. These may just be bold face names to us but these were running buddies with whom he would go on a pub crawl.

He began writing radio and television plays, one-act works, and finally the creations he would become famous for, starting with R&G.

Uniformly, his plots and themes defy any kind of elevator pitch without robbing it of all the things that make it worthwhile. Throughout decades of multi-tasking projects, he immersed his works in evolving philosophies beginning with “Order in chaos, chaos in order.” Sometimes, he would use one of his radio plays or an earlier one-act like Artist Descending a Staircase and make it the foundation for a full-fledged work like Travesties.

Viewing the mind of a nuts-and-bolts craftsman but also a never-satisfied artist, we watch Stoppard changing and rewriting many of his plays not just after they premiere, but during a sold-out run (something pretty verboten on Broadway) — even after the first edition of the script is published, even after the second edition.

As his popularity widened, his circle of connections included political and philosophical figures. He began adult life as conservative – later a Thatcherite – with little feeling for his homeland being overrun by the Communists. Lee clearly tracks his incremental awakening as an emerging progressive political activist deeply concerned about Czechoslovakia, especially seen in his bonding with fellow-playwright and politician Vaclav Havel.

Lee, who received Stoppard’s modest approval and his considerable cooperation, tracks his story to last spring when the pandemic shut down his most recent play, the award-winning Leopoldstadt. Given the years it took to complete this task, it is understood that she venerates her subject, but she rarely editorializes with admiring adjectives. She sees him clearly, acknowledging, for instance, his persistent reticence to embrace his genealogy, religion and country of origin. Clearly fascinated by this, Lee makes past generations and their influence or initial lack of it on Stoppard as a major theme running through the book. She starts her story with detailed intricate histories of branches of forebears going back to the 19th Century. After the table of contents, the first item in the book is a double-page family tree.

She delves into Stoppard’s personality – not making educated guesses but based on seemingly having read everything he ever wrote as well as having long conversations with him, his family, his friends, his colleagues and perhaps his garbageman. But she acknowledges that for someone living so publicly with panache, someone with so many close relationships, he is intensely shy and private. Even some of his close friends say they are not sure they really know the real him.

Readers may agree, even after 872 pages, but he is a fascinating enigma.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design