By Bill Hirschman

The terror underlying Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver and Stephen Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd is that madmen walk among us ignored until their lives of quiet desperation explode or, if we’re lucky, they just melt down.

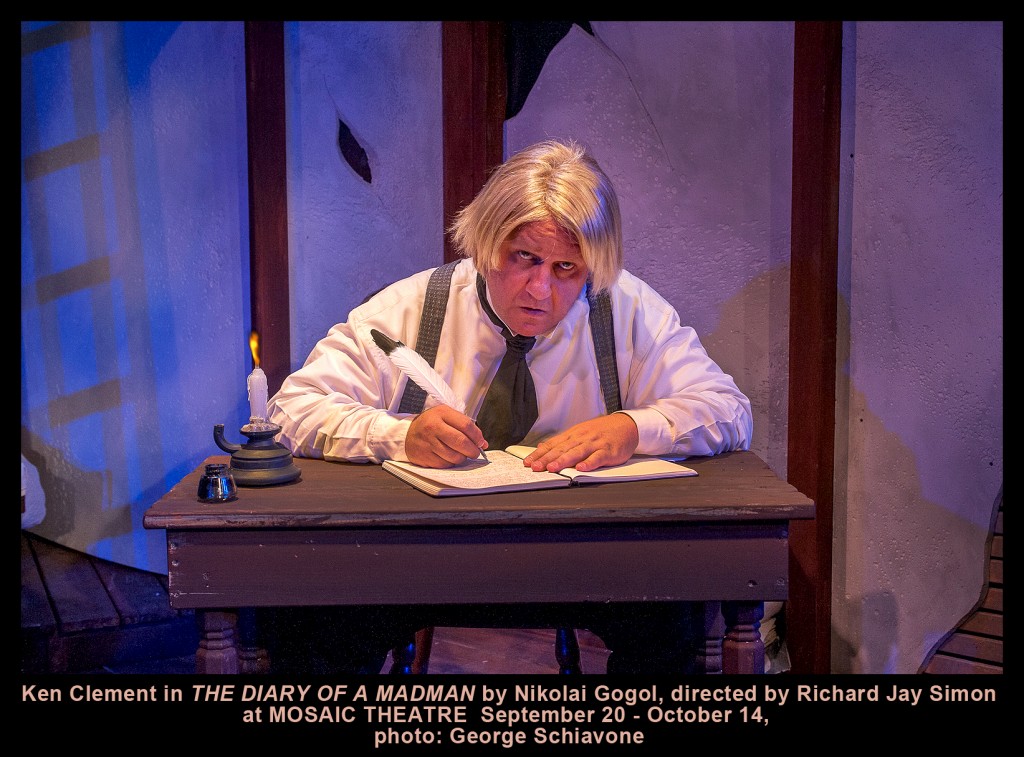

Their deteriorating orbit is tracked with impressive skill and infinite variety in Ken Clement’s bravura tour de force as the government drone Poprishchin under Richard Jay Simon’s direction in Mosaic Theatre’s 12th season opener, The Diary of a Madman.

The production is not an unalloyed triumph, but Clement and Simon excell with their superb depiction of a supremely ordinary individual slipping step by step toward extraordinary lunacy.

Given Clement’s nebbishly amiable persona and bottomless skill set as a vaudevillian clown, Poprishchin’s self-deluding vanity is endlessly funny even as he twirls off into madness. But it is quietly unnerving because Poprishchin’s litany of rationalizations for his failures sound uncomfortably like the self-pitying rants of the lady in the cubicle next to you at work, or the protestations of the guy in the mirror.

Most plays about emerging insanity usually prompt people to say the arc of the evening is a “descent into madness.” But Simon creates an ascent into ever-more rarified strata of psychosis – until the precipitous fall in the final scenes.

The script is drawn from a short story by Russian master Nikolai Gogol, ascribed by several sources to various times in the second quarter in the 19th century. It was adapted as a play in 1989 by David Holman with the help of actor Geoffrey Rush and director Neil Armfield for their Australian theater company. They revived the work in 2011 at the Brooklyn Academy of Music with Rush reprising the role.

Gogol’s tale was an intuitively psychological study before Freud was born, but meant as a wicked social satire portraying an Everyman whose humanity is crushed out of him by the insensitive wheels of bureaucracy and an equally uncaring society. It is meant to be highly comic and ultimately tragic.

Poprishchin takes inordinate pride in the only thing he can, his post as a “ninth grade clerk” whose prized duty is preparing the quill pens used by the department’s director. Writing in a diary in his claustrophobic garret, the slug gathers his frustrations at not being appreciated, his growing anger at society’s snubs and his unsatisfied daydreams about his boss’ lovely daughter. He pours all of them into stream-of-consciousness entries that he reads aloud to himself and re-enacts as he writes. His only visitor is a hapless, even more downtrodden housemaid delightfully inhabited by Betsy Graver. The Finnish immigrant’s inability to communicate in anything but an amusingly befuddling babble just underscores Poprishchin’s alienation from the outside world.

For two acts, Poprishchin holds forth alone in his room. Slowly, we see his lucidity unravel, as his threadbare but fastidious apparel becomes increasingly askew and his Paul Williams mop of hair becomes ever more unkempt. The gentle evolution allows the audience to keep laughing even as Poprishchin genuinely believes that he hears two dogs talking and have written each other letters. The audience knows the inevitable outcome simply by applying a bit of extrapolating imagination to the title.

Simon’s production features dozens of silent grace notes such as when Poprishchin takes off a shoe exposing a bare toe sticking through a sock, or when Poprishchin twists the long loose arms of a jacket around his hands in a silent show of anxiety in extremis.

Before beginning the considerable praise this production has earned, a stabilizing note. Despites the Herculean efforts of everyone involved, the production doesn’t quite land right and may leave audiences impressed but unsatisfied. It takes Poprishchin a long time to get where he’s going, necessitated in part by making the gradual evolution credible. But it’s punctuated by long, long, long arias of nonsense such as reading the detailed ravings that he imagines are contained in the dogs’ letters. This provides gifted artists like Clement and Rush the opportunity to luxuriate in displays of comic inventiveness. But the plot and character points are made early in these diatribes. Also, Holman saddles Poprishchin with an appropriately grand vocabulary and syntax that is so affected and overwrought that it’s difficult to relate to Poprishchin as a stand-in for ourselves.

That said, pull the thesaurus out of the drawer to describe Clement’s performance under Simon’s guidance. Clement has proven year in and year out that he is among the finest actors in the region, showing his range from his haunted talent agent in Faith Healer for Inside Out to his satanic stranger in Mosaic’s The Seafarer to last year’s central character in Jacob Marley’s Christmas Carol for Actors Playhouse. Even at his most comic, he communicates an underlying sadness or even menace. In this case, he is both a figure of risible foolishness and yet someone to feel empathy for as he draws himself to his full height while imagining himself a military general – while wearing a child’s hat folded from a page of newsprint. Clement throws himself unreservedly into this meld of secret self-doubt papered over by self-delusion that veers into fixations.

He enlivens Holman’s ravings with a catalogue of voices and expressions, including different French accents for the two dogs. He creates a surprisingly mobile Poprishchin is in his tiny digs, twisting and turning with his arms as animated as his legs.

The script must have been daunting to memorize because of Holman’s penchant for dialogue that trails off half-finished into silent thoughts. Clement and Simon invest every single one of these sentence fragments with some kind of intent even if it is not articulated.

Simon poses Poprishchin standing, sitting, lying down, even stepping off the stage and out of reality for some musings. He has the self-styled gentleman dive to the floor like a linebacker chasing a fumbled ball when the lovely daughter drops a handkerchief. Every time the lights go out to denote the passage of time, Simon stages the next scene so that the lights come back up on Poprishchin in a completely different pose that denotes a marked advanced stage of deterioration.

Some applause, too, for Graver – who will be seen all over the region this season including GableStage’s Venus in Fur. Her befuddled serf muttering to herself as she works or trying to understand Poprishchin ‘s increasingly bizarre behavior is delightfully silly.

Kudos are due to Douglas Grinn’s set design of a hovel with peeling plaster exposing the rotting wood lathe underneath – a nice metaphor. Also appreciate John Hall’s subtle lighting changes, K. Blair Brown’s costumes and Matt Corey’s procession of period Russian music for the scene changes such as Rimsky-Korsakov’s “The Great Gate of Kiev.”

Beyond its faults and its don’t-miss performance, Mosaic has created an entertaining yet unsettling examination of that accumulation of tiny soul-scraping assaults to human dignity that Jules Feiffer called “little murders.” And you might ask yourself, are you the perpetrator or the victim?

The Diary of a Madman runs through Oct. 14 at Mosaic Theatre inside the American Heritage School, 12200 W. Broward Blvd., Plantation. Performances 8 p.m. Thursday-Saturday, 3 p.m. Saturday, 2 p.m. Sunday. Tickets $40 adults, $15 students, $36 seniors. For more information, call (954) 577-8243 or visit www.mosaictheatre.com.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design