By Bill Hirschman

By Bill Hirschman

Certainly, The Mountaintop is about civil rights, it’s about Dr. Martin Luther King’s place in the struggle, it’s about King as a three-dimensional person, flawed but justifiably honored.

But the play at GableStage examines a more universal issue of how ever-present mortality makes impossible reaching an ultimate goal – which makes the pursuit all the more laudable. We must hand off our most cherished efforts to another generation to cultivate.

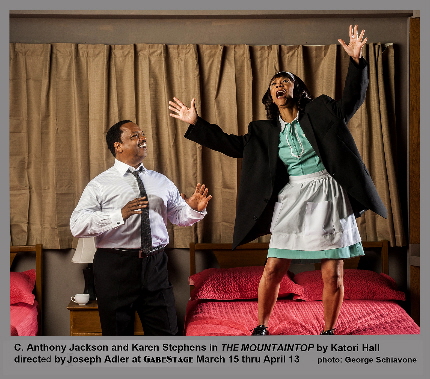

The result under Joseph Adler’s direction and superb work by actors C. Anthony Jackson and Karen Stephens is a moving exploration of the meaning of a life’s achievement leavened with copious amounts of humor.

Their most impressive achievement is persuasively negotiating the sharp left turn that the tone of Katori Hall’s script takes about halfway through when its slips from naturalism (despite hints of something off-kilter) into an unabashed fantasia in which King glimpses his imminent fate. This is a theater piece not a History Channel episode, and audiences should keep that firmly in mind from the outset. To say much more would spoil the subtly prepped reveal – and we encourage everyone not to give it away.

The GableStage team doesn’t always dodge Hall’s potholes – there’s an absurdly risible scene in which King talks to God on the telephone – but the trio mostly convinces the audience to accept similar slides into imagination.

The play opens as a weary, hoarse King trudges into his accustomed room at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis on the rainy night of April 3, 1968 – the night before he will be assassinated. As we have heard replayed before the drama starts, he has just delivered the tragically prophetic speech about not minding not seeing the ultimate achievement of freedom because God has taken him the mountaintop and he has seen the Promised Land. He paces the room, talking to himself as you do when you’re alone, practicing his speech for the next day and checking for eavesdropping devices.

When a lively, attractive maid arrives with some coffee, he could use the company – as well as her proffered cigarettes. Her sassy attitude and profane language (“I’m cussing more than a sailor with the clap”) attracts him and she is clearly enamored of his greatness. Both are far more than what we expect: Camae is more intelligent and thoughtful than we first think. King is a man of gravitas and import, but also a little vain, justifiably paranoid about the FBI and jumpy at every crack of lightning.

Although a few sexual sparks arc between them, both have other things on their mind. They begin sparring about whether King’s non-violence is effective compared to the aggressive credo of the slain Malcom X and the Black Panthers.

Camae is more than just a sounding board, but a participant as King goes through the multiple stages of grief and works his way through the kinds of self-doubt about an unfinished legacy that plagues any leader from the president of a country to the chairwoman of a VFW auxiliary. By the time the intermissionless 90 minutes is over, King and we with him have experienced virtually every word of his final speech. Those sentiments reflect how he comes to peace with the idea that the baton must passed to his followers and, in a direct exhortation at the play’s finale, to us.

Hall’s script is mostly effective and challenging in switching between recognizable reality and fantasy, poignant drama and open-throated comedy, but all daubed over with a scrim of compassion for the universal plight of being doomed. She convincingly depicts a man with doubts not just about himself but about Humankind’s innate fear of who and what they aren’t familiar with. At one low point, King says of blacks and whites, “We hate too easily. We love too easily.” Hall goes a little too far sometimes, such as when King makes utterances like “over my dead body” or Camae saying “Civil rights’ll kill you before Pall Mall (cigarettes) will.”

Adler is a famously strong-willed director who uses actors as tools to create his vision on stage while considering their offered ideas. So while his direction is rarely flashy and self-conscious (other than a love of a dramatic use of sounds and lights), what you see often on his stage is a lot of Adler. Given the difficult shifting tones of this piece, it is his pacing and staging and sculpting that makes it work as well as it does.

Obviously, at least one linchpin has to be the actor portraying an iconic figure we have seen and heard scores of times. Jackson is not King’s doppelganger, but he has made a second career speaking King’s words. As a result, his resonant baritone embraces King’s public speaking patterns and cadences forged in the pulpit. But Hall is not depicting that King.

She, Adler and Jackson are portraying the human being, not the saint chiseled into stone in the monument off the National Mall, nor the revisionist portrait of a man so morally compromised that his aura is deeply tarnished. Jackson’s King is simply a man, a profoundly admirable man with shining virtues, yes, but a recognizable human being whose multi-faceted character makes him relatable. And that humanity underscores Hall’s theme that every person has the seeds of achievement and the responsibility to work for a better world.

It’s only fair that I point out that I’ve been a fan of Stephens for many years and, in the spirit of full disclosure, I appear with her on Iris Acker’s weekly television show on BECON TV. Now with that out of the way: Stephens is simply brilliant as Camae. No asterisks. Her work is breathtaking whether she’s defiantly but adorably whipping back some attitude in response to King’s sexism, or standing on a bed slyly lampooning King’s preacher’s cadences — except in service of her more violent philosophy, or when she relates the murder of a young woman who intuits the roots of the killer’s pain but hates him for his violence, or her transcendent monologue about the forgiveness of God.

Stephens has a large range vocally and physically as she has shown in her one-woman show Bridge and Tunnel; here she uses mostly a reedy top-of-the-throat voice that sounds perpetually askance at King and what transpires.

Camae joins her brief turn as the pragmatic mother in Maltz Jupiter Theatre’s Doubt and the emotionally-scarred veteran in Zoetic Stage’s Fear Up Harsh (both Carbonell nominated this spring) for a trio of stunning performances in less than a year.

Everything occurs in an effectively naturalistic representation of a clean if modest motel room created by Lyle Baskin which features inclement weather outside the window. As always, it is ratcheted up a notch by Jeff Quinn’s lighting design which subtly changes even in the first half of the play to highlight moments such as Camae’s faux preacher speech. But his design gets a workout in the second half when stranger things occur. Matt Corey’s sound, obviously shaped by both the script and Adler, is a more mixed bag: the sound effects are sterling as always, but some overwrought music keeps cropping up to unsubtly underscore dramatic points, especially when the play takes its left turn and several times thereafter.

The road may twist a bit, but the trip to The Mountaintop is worth the climb.

The Mountaintop runs through April 13 at GableStage, 1200 Anastasia Ave., Coral Gables, inside the Biltmore Hotel. Performances 8 p.m. Thursday-Saturday, and 2 p.m. & 7 p.m. Sunday. Runs 90 minut4es no intermission. Tickets $52 – $55. For tickets and more information, call 305-445-1119 or visit GableStage.org

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design