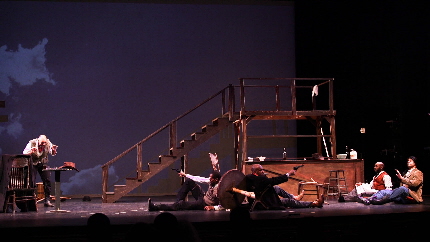

The guns are drawn as a tornado is bearing down on the saloon in the National Black Theatre Festival’s production of Cowboy.

By Bill Hirschman

In Cowboy, the new dramatic play opening in June at M Ensemble in Miami, the gun-totin’ U.S. Marshal Bass Reeves, traditionally garbed down to the required Stetson, strides through the double doors of the saloon, secretly on the trail of two wanted criminals.

But there’s a slight difference from the oaters in which Sheriff John Wayne restored justice to a sleepy town. The lawman in Layon Gray’s play is Black.

The specifics of the tale are fictional and on one level they echo familiar Western tropes. But Reeves was a real person—the first Black U.S. Deputy Marshall west of the Mississippi, apprehending an estimated 3,000 suspects over 32 years.

Yet beyond Gray’s desire to tell an entertaining story that Duke Wayne would recognize, Cowboy’s 1888 narrative arches over deeper themes. Reeves and his Black quarry are a generation trying to define true freedom only 23 years after the end of slavery—still wrestling the lasting aftermath of their nightmarish personal pasts.

“We touch a lot on the journey from African Americans from being in chains to being free,” Gray said a week into rehearsals. “People get a history lesson, but they aren’t hit over the head with it.”

But this current production coincides with a groundswell of American theaters across the entire spectrum committing to addressing inequities in hiring, leadership and play selection of artists of color.

That dovetails with the work of this oldest continuing Black theater company in the state as it enters its 50th year, said Shirley Richardson, executive director/artistic director and co-founder. “That’s part of our mission… to keep alive our history, because the history of African Americans in this country is hidden.”

Co-founder and general manager Patricia Williams added immediately, “M Ensemble likes to perpetuate and to cultivate our history.”

Williams and Richardson immediately latched onto the work when it premiered virtually with ink still wet on the pages at the 2019 National Black Theatre Festival, held every two years in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Gray had delivered one of M Ensemble’s most high-profile triumphs in 2017, writing, directing and designing his play The Kings of Harlem about the rise of the all-Black 1939 New York Renaissance basketball team. The production won the Carbonell Award for best production of a play, best director of a play and best supporting actor for André L. Gainey. The company also produced his Meet Me at the Oak in 2019.

This story depicts Reeves and his Native American colleague in a small town in Oklahoma Indian Territory in 1888 as a tornado is bearing down. His two malefactors are the Colton brothers fleeing to Mexico. Like Reeves, they were born into slavery and hoped to find a new life in the open spaces of the West.

While the real Reeves shot 14 men, he and his fictional counterpart prefer to bring in culprits alive by locating them with detective work and then conning them or reasoning with them to surrender—when possible.

“You have that cat and mouse game between the marshal and the wanted criminals that he’s trying to capture,” Gray said. Violence is always possible “but (Reeves) takes (one brother) back down memory lane when they both identify with what each of them went through back in those days” of slavery.

If most white audiences have never heard of Reeves, he has been mentioned in varied accounts of African Americans who spent Reconstruction, often as cattle-herding cowboys and Buffalo Soldiers. Reeves has been the real-life subject or fictional character in novels, television episodes of westerns, even video games—yet still mostly unknown in white culture.

Richardson not only knew about Reeves, she said, “I had a big poster of him and other cowboys. I always collected cowboys.” Indeed, she had heard the legend proposed in a 2006 book that The Lone Ranger created for radio in 1933 was inspired by Reeves because they both had a Native American partner, rode a white horse, gave out silver keepsakes and had other similarities.

But he was unknown to Gray. “I had no idea about Bass Reeves and Black cowboys because growing up we’ve (only) seen on television where there was Wayne and various other white cowboys. I had no idea Black cowboys existed.” He was researching a play about African warriors when he stumbled across an article about Reeves.

The idea intrigued Gray. He has been drawn to delving into African American history during his career over two decades as a playwright, screenwriter, director and designer. One of his most produced works around the country is Black Angels Over Tuskegee, portraying the efforts of six Black men to become pilots in the U.S. Army Air Forces—a play that ran for years Off-Broadway.

“It’s just the telling of the stories. I just love bringing stories of life that no one has never heard of, just bringing this history on stage, because film is forever, but nothing can compare to theater coming right in your face,” Gray said.

The existence of Black cowboys has been toyed with in movies—not so much theater—for decades. One list (click here) cites 43 movies dating back to John Ford’s Sergeant Rutledge in 1960 centered on a Black Calvary soldier played by Woody Strode being court-martialed. The films range from blaxplotation films of the ‘70s to Jamie Foxx’s 2012 hit Django Unchained. But the entire idea of a Black cowboy-lawman was so alien to the cultural expectations of most white audiences for decades that it became the underlying joke for Cleavon Little’s character in Blazing Saddles.

Gray overhauled the script after the North Carolina debut and a second production the same year in Pittsburgh.

Playwright-director Layon Gray will be playing the lead as well

In this outing, he not only directs, designs projections and is bringing script changes to rehearsals almost daily, but—unable to find precisely the right actor for the lead character—he is reluctantly taking the central part himself. Having not acted in a little while, he laughs admitting to the irony of struggling to learn the lines he himself wrote.

Other in the cast are Reggie Wilson, C.L. Reuben, Isaac Beverly and Jaerez Ozolin.

The production comes as artists of color are in the spotlight as the theater industry responds to allegations of institutionalized racism with reforms propelled further with the emotions fueled by the Black Lives Matter movement.

Artists like Gray watch carefully this current “trend” in which artists of color are being hired to helm mainstream companies and most regional theaters are planning multiple shows written by and performed by diverse artists.

“I hope this isn’t just like a quick media grab, because there are so many qualified people of color who could hold these (leadership) positions. People are getting positions that they probably could have had a long, long time ago. And (theaters) need to continue pushing African American playwrights,” Gray said. “I do hope that this is continuing is not just the trend. I think we’re going to see some change in the arts when it comes to the art itself.”

M Ensemble, of course, has been a home for artists of color for a half-century as opposed to other theaters that might include a single play about African American issues once in a season, if only to further grant applications.

Williams joked dryly, “We were doing this long before Black Lives Matter.”

While they obviously have a core audience of African Americans, they also want their works to be an educating force for the whole community.

“We produce plays for everyone, so that the Caucasian community will understand our history, too. They don’t have the knowledge that we had this much history,” Williams said.

But now the two co-founders are looking ahead with hopes for the survival of the company and the effort they have devoted their lives to.

“There’s a whole new generation out there. It’s a whole new ballgame” with diverse artists represented on cable, in film, with online efforts, Richardson said. “We’re looking to see who is willing to make the sacrifices Pat and I made to continue this journey. We’ve put too much of lives into this to see it close up. This is a legacy.”

Cowboy from M Ensemble Company runs June 11-27 at the Sandrell Rivers Theater at the Audrey M. Edmonson Transit Village, 6101 NW 7th Ave (parking garage 6101 NW 6th Court); 8 p.m. Friday-Saturday, 3 p.m. Sunday. Tickets $16 general admission in advance, $21 at the door. Social distancing invoked and masking required. Call (786) 773-3161 or visit themensemble.com

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design