By Bill Hirschman

You leave some plays not certain what you’ve seen. You have to chew it over with others on the way home. You’re still rolling it around in your brain days later.

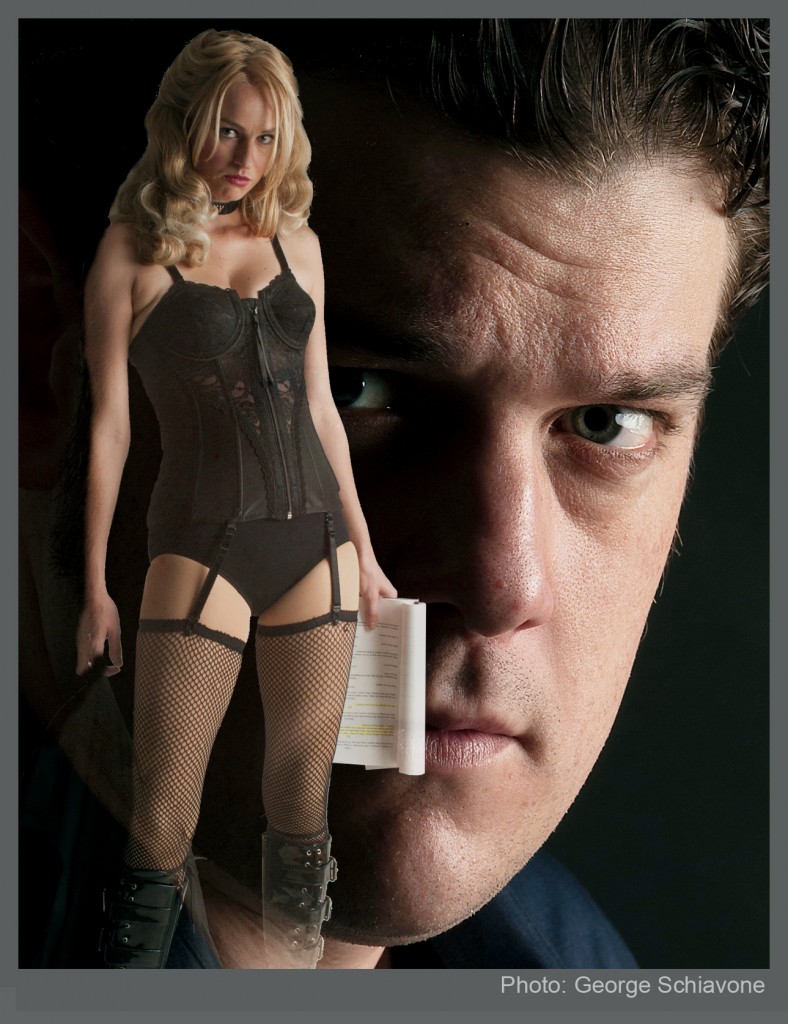

In the case of GableStage’s production of the message comedy about sexual politics, Venus In Fur, the only thing to be certain of is the stunning performance by Betsy Graver. She creates a mysterious actress who seems a bubble-headed bimbo one moment. In the next, the same character preternaturally inhabits the part of the cultured noblewoman that she is auditioning for. Then the ditz is back again, literally in the space a few seconds.

It is a star-making role for Graver who has worked hard for the past few seasons in supporting parts in The Motherf**ker With The Hat, Blasted and Time Stands Still at GableAStage. The tour de force did the same for Nina Arianda, a recent college graduate who created the role off-Broadway in 2010 and repeated it on Broadway in a Tony-winning performance in 2011.

You’re not likely to have the same epiphany about what playwright David Ives is driving at with this intellectually stimulating, but thematically murky story – and we say that having seen the Broadway iteration as well. Still, that’s okay. Art doesn’t have to be so easily digested and diagnosed while you’re still sitting in the theater.

Just savor the work of director Joseph Adler, actor Matthew William Chizever as the playwright/director auditioning Graver’s character and GableStage’s familiar team of crack designers.

The script charts a bizarre pas de deux that begins when the scatter-brained Vanda arrives hours late for an audition. The play is an adaptation of Sacher-Masoch’s 1870 novel Venus In Fur which explored a man’s infatuation with a woman so profound that he begs her to allow him to become her slave.

The play’s writer/director Thomas is alone, exhausted and packing up to go home in the teeth of a thunderstorm. In bursts this Alicia Silverstone on speed from Queens. She entreats him to allow her to audition although her foul-mouthed rough-hewn persona makes her about as unlikely a candidate as you could conceive. Undaunted, she takes off her bright pink raincoat to reveal that she has bought a leather and lace outfit to match the part, plus a spiked dog collar and a ruffled, translucent gown.

She does not seem the sharpest blade in the drawer: “This is like based on something, isn’t it, besides the old Lou Reed song?” And she is fascinated by the S&M aspect: “Do you think this is porn, or porn-ish, you know, for medieval times, or 18-whatever?”

But when she auditions with Thomas perfunctorily reading the other part, Vanda instantly subsumes into the well-spoken self-possessed lady. Thomas is intrigued despite himself and is drawn into reading the script with her even though he is not an actor. And although he claims not to have an affinity for the domination fixation of the novel’s central character, he, is seduced into what becomes role-playing rather than acting. Over the next 95 minutes, lines blur between the characters and the evening rolls toward several surprises in the last 15 minutes.

Again, the precise point is a bit elusive other than idea that the fantasy of domination by either sex is not a healthy foundation for any relationship. Instead, it is simply demeaning. Well, duh. What Ives and Adler have succeeded at is documenting the swirling shifts in the balance of power in a relationship. But the play seems a lot of effort for such an obvious payoff. That’s where a little cogitation over time may reveal more facets.

On the other hand, Ives, Adler and Graver inject copious amounts of welcome humor. Much of this occurs when Graver switches effortlessly between the two personalities. Often, her rendition of the woman in the novel lulls you into forgetting you’re watching “a part” because she speaks flawlessly in bell-like tones with perfect pronunciation such as caressing the word Renaissance with the cultivated long A. Then, Vanda the actress explodes like a waitress at a strip club as she tumbles to an obvious development in the script. The juxtaposition is hilarious.

Ives also drops in snappy repartee: When the director has trouble playing his part, he says, “This is hard. I can’t believe I put actors through this.” To which Vanda teases, “You’re a playwright. You’re a director. It’s your job to torture actors.”

The yin and tang of Vanda’s character are exemplified through what Graver and Adler have created with vocal tones, body language and timing Graver makes the utilitarian rehearsal room vibrate with an ebullient, nervous energy as she clumps around the room, flashing a huge grin that exposes an endearing overbite. Then, her posture morphs into a regal erectness and her voice acquires a polished measured cadence. One of Graver’s less obvious but fully impressive achievements is her almost imperceptibly gradual melding of the two sides of Vonda until a third person emerges.

As her partner in the dance, Chizever exhibits that smooth, seamless leading man quality that mirrors his warm baritone voice. The fact that Ives has given him a less showy role does not detract from Chizever’s solid depiction of a man headed for a serious fall. His Thomas starts out a sophisticated intellectual with a bit of a pedantic streak and a poorly-concealed condescension to the hoi polloi. Over the evening, his persona, even his accent, slips into that of the novel’s besotted protagonist. It is his work that makes the ludicrous arc of the play somewhat believable. Unlike the hunks who performed the role in New York, Chizever makes the descent even more credible and relatable because while he is certainly handsome, he is not movie star dazzling.

As usual, Adler keeps up the momentum as well as shapes the actors’ performances. But the difficult-to-follow muddle that Ives gave him to work with means that many befuddled audience members are going to want the play to end more quickly.

In the different strokes for different folks department, Graver’s Vonda is undeniably alluring in her bustier, long blonde hair falling past her shoulders, draping her long legs over a divan. But neither this nor the New York production seemed especially erotic or sexy.

And finally, be warned: The entire play takes a wild stylistic left turn in the last 90 seconds as if Superman flew in the window at the finale of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf. It’s not that Ives hasn’t been prepping us all night for the internal logic of it. In retrospect, you recall a dozen little mysteries peppered throughout the play that now make sense, such as Vonda having the entire script memorized when no one has seen the script. But it’s one strange explanation.

Still, Venus In Fur is a solid way to kick off GableStage’s 15th season with a kaleidoscope of sexual power in which we’re not sure who is on top, literally or figuratively.

Or maybe a cigar is just a cigar.

Venus In Fur runs through Dec. 9 at GableStage, 1200 Anastasia Ave., Coral Gables, inside the Biltmore Hotel. Performances 8 p.m. Thursday-Saturday, and 2 p.m. and 7 p.m. Sunday. Tickets $37.50 – $50. For tickets and more information, call 305-445-1119 or visit GableStage.org

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design