By Bill Hirschman

By Bill Hirschman

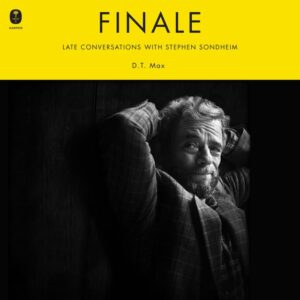

Finale: Late Conversations with Stephen Sondheim, by D.T. Max, Harper, $20.99, 244 pages

Backing into this: Early last month, deep into reading D.T. Max’s modest new volume Finale, which documents a handful of conversations with the legendary but aging titan, Barbara Walters’ interviewing process came to mind – ironically a few weeks before her death.

Walters was a brilliant interviewer who elicited thoughts, comments and revelations from her subjects that had unprecedented depth. But the 15-minute interviews you saw on 20/20 were a small part of hours and hours of interviewing she did with the same person. On point here, you also did not see her hours of priming the pump by sharing secrets and stories of her own past, and creating a sense of trust. This has been a journalism tactic for centuries, but for the most part, until the 1970s, the author’s interactions with the subject usually had been omitted from what got printed.

Thereafter, a new journalistic storytelling approach evolved in which the reporter became part of the storytelling. But not to this extent in Finale: Late Conversations with Stephen Sondheim. We’re not interested in the interviewer’s life, loves, food preferences and car debt. Finale goes an unwelcome step further.

D.T. Max apparently had so little actual productive or revealing interview time with Sondheim in his last years that the only way to fill 224 pages was to spend nearly half of it talking about himself, his efforts to interview Sondheim and his other non-Sondheim projects in the mill. Then he spent a good deal of the interviewing process reproduced here (a process we journalists all have done) schmoozing and talking about anything but about the topics at hand.

The title’s word “conversations” is apt because this basically reproduces a handful of abridged back-and-forth talks directly from taped interactions. Some might be called semi-formal interviews, but others, during the same meeting, it’s just a couple of guys shooting the breeze. Part of one interview chapter occurs at a PEN gala that Sondheim participated in. Max takes significant time in this chapter recounting Sondheim and fellow guest Meryl Streep bantering at length backstage. (Max apparently never turned off his tape recorder ever).

There is no arguing that anything we devotees can learn about Sondheim is precious to us. Indeed, Max has made us feel like we are there in the room bantering with the Master, obviously something few of us had the opportunity of doing.

But clearly, Max is almost as crucial, at least to him, for what’s in this book as what Sondheim says. At one point, Sondheim mentions that Max looks like actor Geoffrey Rush, but Max responds in a post-interview add-on that most people mistook him for Nicholas Cage when he was younger. And we care, why?

One really interesting side note: These five interviews, if that’s the right word, spread from 2017 until 2019 were meant to be for a major magazine piece that never ran. Max got a couple of short pieces done for The New Yorker, but Sondheim balked after the final interview, and, in effect, nixed Max’s planned opus let alone this book. Deal with that.

And yet, give credit where credit is due, Max succeeded (around discussions of their mutual interest in dogs) in getting Sondheim to reveal glimpses of his work process and thinking, so we have to thank Max for that.

It is mildly fascinating to hear Sondheim interacting with someone in this mélange of real life and journalism. It does, indeed, reveal aspects of his off-camera personality that have rarely been recounted in any detail.

And there are a couple of dozen passages in which Sondheim analyzes his work and his process in a look back.

—He speaks of building a score that coheres, that develops an overall musical theme as Sweeney did. “How do you make it more than just a set of add-a-pearls.” It contrasts with works like Carmen of which he said is “twenty of the best tunes you’ve ever heard in your life, but they are twenty different tunes.”

—He talks about how the audible aspect of rhyming is important but it is crucial that it works within the sense of a song. “It’s about making a rhyme that clicks. It’s like sinking a pool ball into a pocket.”

—He talks about how he had wanted Sweeney Todd to be an intimate production, but producer/director Hal Prince made it the massive social opera it became.

—At the time, he was working on the never finished show based on two Luis Bunuel movies as well as advising productions such as Bobby-as-a-female tryout in London’s Company. But he noted that his work process had slowed considerably as well as much else in his life at age 91. Clearly, the process never got easier for him.

—He provides insights such as how the outstanding performances of the leads in the original production of Follies were so perfect from the instant the actors appeared on stage that it wasn’t a problem that there were not mountains of character-revealing dialogue in a show with 23 musical numbers.

Throughout, there are plenty of off-topic exchanges, some relating to music (He didn’t like much popular music but he found The Beatles “exceptional” and thought Radiohead worth mentioning). Other items just provide fascinating insight into the man but that have little to do with the creation of theater such as a brief mention of John Ford movies in which Sondheim favors The Grapes of Wrath rather than The Searchers, and adds that he appreciates Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt but feels Vertigo is overrated.

Max is as a journalist covering a wide array of topics like an old general assignment reporter at a newspaper, so while he genuinely appreciates theater and especially Sondheim, he’s not half as knowledgeable as many of his readers will be. For instance, he is not familiar with whom Yip Harburg is when Sondheim mentions him.

And he apparently only did minimal homework such as not reading the Meryle Secrest biography because he didn’t know of Sondheim’s now documented problems with his mother (in that volume we learn she told him she wished he hadn’t been born) but who Sondheim here talks about basking in his reflected popularity when he became a celebrated success.

But look, we are grateful for the insights Sondheim shared with Max, and this book, for better or worse, is like getting the chance to kick back with a fellow human being who just happens to be a venerated genius.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design