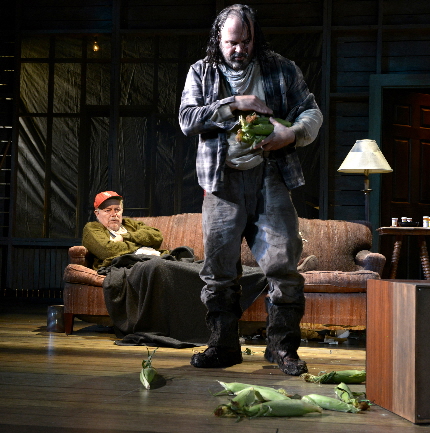

Rob Donohoe and Paul Tei as two members of the venal family in Palm Beach Dramaworks’ Buried Child / Photo by Alicia Donelan

By Bill Hirschman

“Home” sparks many homilies: Home is where the heart is. Home is where they have to take you in. But Palm Beach Dramaworks’ intellectually and artistically thrilling production of Sam Shepard’s Buried Child is not about home alone, but about family and the abyss between the two ideas.

The homily uttered here is “You think just because people procreate that they have to love their offspring.”

Mounted just in the time for your own round-the-dining-table holiday-in-hell gatherings, Buried Child is a supremely discomfiting investigation into the complex bond among perhaps the most dysfunctional family members ever depicted on stage who, even so, are mutually condemned by the cursed DNA in their shared gene pool.

Dramaworks has two major arrows in its “theater to think about” quiver of revivals: mainstream works like All My Sons and Our Town. And then there are the off-beat stylized works like Edward Albee’s Three Tall Women and Eugene Ionesco’s Exit The King.

Shepard’s Pulitzer Prize-winning career-making play falls firmly in that latter netherworld in which the audience is kept off-balance for two hours as it views the commonplace through a perverted prism worthy of Lewis Carroll and Franz Kafka.

Audience members addicted to straightforward narratives, pleasant content and overt meaning will absolutely hate Buried Child for its toxicity, its requirement that patrons peel back layers of meaning and symbolism long into the car ride home, and especially its ever-confounding surrealism and absurdity.

A quick example: A demented son enters the family home with an armful of corn ripped from a bumper crop outside, even though his aging parents swear, quite believably, that nothing has been planted in 35 years – two irreconcilable yet irrefutable truths.

But resident director J. Barry Lewis is in his element. As always, he helms a superb ensemble committed to this madness with a certitude that gives the audience a steadying assurance that he and they know exactly what is going on, even if you don’t.

But if you can’t or don’t care to parse the levels, you can let the tableaux of desperation and cruelty wash over you. An old man rips the stuffings out of a couch looking for liquor. An unhinged brother pulls his older sibling’s artificial leg just out of reach as the cripple crawls across the floor piteously trying to retrieve it.

Let’s back up. The play opens in the large living room in an Illinois farm during the depths of the 1970s recession. It’s a dilapidated grey musty manse with exposed lathe showing through the plaster walls and the sense that infectious mold of the soul has seeped from the denizens into the cracks of the house (a brilliant creation by set designer Jeff Modereger and lighting designer Kirk Bookman).

Sitting on a desiccated sofa staring at a television on the floor is the burned out alcoholic husk of a human being, Dodge (Rob Donohoe). He is sparingly responding to the persistent acerbic banter of his seemingly flighty wife Halie (Angie Radosh) who is conducting this conversation unseen from a room on the second floor. Dodge is dying and he soothes the ominous hacking in his throat with a bottle of something that is clearly not cough syrup.

Per the script, this first 10 minutes has the two sparring banal chitchat by shouting at each other from separate parts of the house, about as vivid a metaphor as possible for estrangement in a marriage and the disconnect among family members.

Halie appears en route to a meeting with Father Dewis (Dan Leonard) who Dodge suspects she is having an affair with. She hopes the minister will help her raise money for a hero’s statue of a son who died while in the Army but not in battle.

A hulking dirt-smeared Frankensteinish creature appears from the rainstorm outside with that armful of freshly picked corn. Tilden (Paul Tei) is the oldest brother home for the first time in 20 years after a tumultuous self-exile. He seems literally slow-witted — not stupid, but someone whose brain functions have been profoundly blunted by some emotional trauma.

Later we will meet the younger brother Bradley (David Nail) a rough bully who has taken over running the house. He limps around the house with a prosthetic leg because, in classic Shepardmania, he accidentally cut his limb off with a chainsaw.

Finally entering the mix is Vince (Cliff Burgess), the seemingly normal son of Tilden, also AWOL for six years. In tow is his gum-chewing girlfriend of the moment Shelly (Olivia Gilliatt). Both are attractive young people seemingly plugged into the trendy Los Angeles scene of 1979. Vince becomes increasingly unhinged by the fact that no one in the family seems to recognize him, another metaphor, of course. Meanwhile, Shelly, a pre-Valley Girl version of Alice in a very dark Wonderland tries to charm her way through encounters with a group who would be right at home in Deliverance.

Shepard creates seemingly harmless folks who are secretly monsters, and monsters who are actually relatively harmless. And yet everyone in the family has a bent for cruelty, especially Halie who blithely issues nasty statements while seeming completely ignorant of what she is inflicting.

Infused in everything that is said and done is The Family Secret of the title which seemingly warped what was once a classic Beaver Cleaver family into this collection that would terrify the Addams family. But in fact, as the last scenes show, the rot always festered deep inside the family’s genetic makeup. Shepard contends that the nuclear family facet of the American Dream is a concocted sham. As the play progresses, The Family Secret seems to bubble up from the farm’s fetid soggy soil like a dinosaur bone emerging from the tar pits.

Under Lewis’ assured direction, some of the region’s finest actors deliver outstanding performances. Start with Donohoe whose chamelonic work for Dramaworks has included the quiet terror of the cultured well-to-do houseguest in A Delicate Balance. That Brahmin is unrecognizable in this grizzled dying reprobate with a combative craggy voice. Late in the play, Dodge reveals to Shelly the rotting meat of The Family Secret. Donohoe’s aria, delivered by him splayed but motionless near the front of the stage, is a master class in hypnotic you-can’t-look-away storytelling of a real horror tale.

Radosh, one of the great actresses in the state, creates a pearl-wearing monster who has deluded herself that she is the only normal sinless person in the family when she is as much a fiend as any of them. Her Halie, living completely inside herself, hurtfully flings judgments as if the person in question isn’t even present.

Tei has been so busy with roles on television and directing the works of his Mad Cat Theatre Company that his infrequent appearances on stage make it easy to forget what an accomplished actor he is. His Tilden is a stolid man whose mind has been so badly broken that he has become an elemental creature responding dully to only the most insistent stimuli. Tei’s face reflects Tilden’s slow laborious processing of information as it fights its way through his synapses. When he stares hungrily at Shelly slicing carrots like she is a lovely visitor from another planet or when he rubs her rabbit fur jacket over his face, it’s hard to isolate whether Tilden is hilarious or terrifying or both.

Burgess’ Vince initially seems like a slick semi-sophisticated hipster, so far removed from the moral decay of this family that you begin to wonder, as Shelly does, whether he has made up his connection to this group. But Burgess comes roaring back in the last act with an appropriately over-the-top explosion as the chromosomes come home to roost.

Nail, who made a wonderful redneck sexist pig in Arts Garage’s Exit Pursued By A Bear, convincingly portrays a blunt bellowing bully who then becomes an emasculated shell when deprived of his leg. Dan Leonard is delightful as the ecclesiastical visitor and adulterer trying hard to not to be nonplussed by the insanity around him.

Gilliatt, the only ringer from outside the region, creates a character who initially seems as shallow as a Kardashian, but who eventually is revealed as the only sane person with any decency, even someone yearning for some kind of family.

Among Lewis’ strengths is pacing and he courageously allows the play to breathe, from the freighted silences in conversations to the extended silent scenes such as Tilden “burying” his sleeping father under a score of corn husks. In moments like these, he allows to us hear the steady rainstorms and far off bark of a dog layered in by sound designer Richard Szczublewski. Physically, Lewis underscores the gulf among the characters by keeping everyone at least a car length away from each other 95 percent of the time, even when they are ostensibly interacting,

Leslye Menshouse’s costumes could not be bettered from the men’s dingy garb that seems as moldy as the walls to Halie’s gladiola garb (which was a black dress when she left for the date with Dewis the night before) to Vince and Shelly’s pop trendy clothing that the characters likely saw in People magazine.

Shepard re-drafted a version of the 1978 play in 1996 when it was revised by Steppenwolf Theatre Company in Chicago. He said there were more ambiguities than he had intended, and he wanted to bring out the humor that he believed was integral to the success of the play. This is that script.

Sadly, Shepard doesn’t get performed much down here. Mosaic Theatre in Plantation did True West, and Buried Child was given a staged reading in 2011 as an early effort by Outre Theatre Company. He can be rough going on several levels.

So Buried Child is not a pleasant evening of entertainment; it’s more of scathing abrasion therapy that purges the mental palate with fare that is as harrowing as a plow etching a deep gash in the land. But it is theater at its best.

Buried Child runs through April 26 at Palm Beach Dramaworks, 201 Clematis Street. Performances are 8 p.m. Wednesday-Saturday, 7 p.m. on some Sundays; 2 p.m. Wednesday, Saturday and Sunday at 2 p.m. Wednesday matinees and Sunday evenings include a post-performance discussion. Runs 2 hours 10 minutes including one intermission. Tickets are $62, student tickets are available for $10, tickets for educators are half price with proper ID. Call (561) 514-4042, or visit www.palmbeachdramaworks.org.

To read an interview with the cast and director, click here.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design