Ian Lake as Macbeth / Photography by Don Dixon.

By Bill Hirschman

The easiest way to grasp a sense of the Festival, its styles and ethos is to recount and review the individual productions we saw during a trip last month. Hidden within may be insights that can be adopted by South Florida theaters.

Breath of Kings: Rebellion and Redemption

Is it audacity when a company believes that it might have the resources and skill to conquer a two-evening alloy of four Shakespeare’s history plays? Will the theme of Power inherent in the individual plays be dissected more incisively across the scope of the conjoined works?

That level of daring is rewarded with this vibrant, enthralling and unnerving indictment of how a lust for power enables the unbridled pragmatism of ambitious people. Those themes are echoed in the Festival’s Macbeth, but the sweep of history here depicted crossing generations underscores that thesis as no single play can.

Veteran actor Graham Abbey spent 15 years fusing Shakespeare’s words into one evening Rebellion, built from Richard II and Henry IV Part I, and then another Redemption from Henry IV Part II and Henry V. The idea is not completely original; similar compilations have existed under other titles on stage and television for a half-century, sometimes throwing in Richard III. But many were episodic; this is all of a piece thanks to Abbey, who served as associate director with co-directors Weyni Mengesha and Mitchell Cushman.

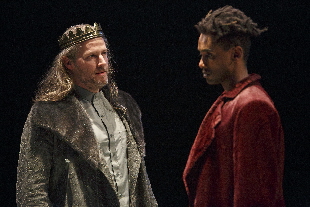

Graham Abbey as King Henry IV and Araya Mengesha as Prince Hal in Breath of Kings:

Abbey and his collaborators create a vibrant and accessible treatise on the human cost of gaining, keeping and losing power. Awash in blood and motives that are sometimes arguable and sometimes indefensible, Abbey focuses on the roots and results of the pursuit. Agile minds will be unable to escape relevancies to modern political machinations.

Experts can spot plenty of excisions that keep each evening to three hours. But the adapters add flourishes that illuminate the source work. For instance, the strangulation of the Duke of Gloucester, which actually sets off this cavalcade, is only referenced verbally by Shakespeare. But here it’s played out in front of the patrons to begin the play. Blood begets blood.

Furthermore, some scenes are carefully rearranged. For instance, the story of Falstaff normally spun across three and a half plays seems more unified so that when the newly-crowned King Henry V spurns him, the effect of his downfall is more moving.

The two evenings are staged as a ritualized retelling of a fable, relying on a high degree of theatricality including ingeniously self-aware double-casting such as the Dauphin and his sister Princess Katherine being played by the same actress. About 20 actors perform about 70 roles, so the off-stage dressers deserve a curtain call.

For the most part, the performances are superb including Tom Rooney’s venal Richard, Abbey’s Bolingbroke who ages over the decades into Henry IV, Wyn Davies as Falstaff, and Araya Mengesha who starts out not too convincingly as a frat party boy Prince Hal but who matures in acting skill and characterization into the multi-faceted pragmatist Henry V.

What amazes is how comprehensible this group makes the complex political maneuverings. For instance, when the clergy argue the bogus Byzantine rationale for Henry to go to war with France, not only is the internal logic clear, but also the moral bankruptcy of the reasoning. Shades of weapons of mass destruction.

No one here is a hero, yet few feel like villains. The adapter and directors depicts them clinically as deeply flawed human beings. Slacker Hal rejects his best friend, Richard confiscates land that does not belong to him, the French slaughter Henry’s teenaged camp followers, Falstaff is a self-satiating liar and thief, loyalties are betrayed and unholy alliances are forged solely in the pursuit of power for its own sake.

The melding of the pieces underscores this arc of actions having repercussions that last decades and also allows us to track how the power players like Henry IV and his son are changed by those repercussions. Throughout, Abbey and the directors alternate scenes of royalty awash in intrigue with scenes of the everyday subjects in the taverns whose fate is at the mercy of these regal maneuverings. Granted, the production loses a bit of energy in the second half, but fortunately Henry V is a beloved play that fans are partial to.

In keeping with the Bard’s sensibility, this production and the other Shakespearean offerings we saw share several elements. First, every creative hand injects humor at every opportunity, ranging from broad farce to witty wordplay to dark gallows humor.

Second, the Festival has a bent for rugged, athletic combat with swords, axes, daggers and pikes, often staged in stylized slow motion amid smoky haze. Especially unnerving here was the epic battle between Prince Hal and Hotspur at Shrewsbury.

Finally, the accents are not the traditional “received British.” A few speakers sport that unique mid-Atlantic intonation. But most orate in a “North American” accent that contains a faint Canadian lilt. Crucially, all of them caress the music of Shakespeare’s language with a skill we never ever hear in South Florida productions, yet they have analyzed the text well enough to put a premium on making the sense of the text comprehensible. The lack of a Gielgud-like sound also makes the work more accessible and welcoming.

Macbeth

Even as the audience finds their seats, thunder rumbles ominously across the large expanse of the Festival theater so convincingly that patrons wonder about the storm brewing outside the theater.

But the storm is inside. The inciting off-stage battle usually described second-hand is depicted amid the dense Highland fog with swinging swords and gory mayhem. Only in its aftermath do the three sisters enter to conjure the showcase work of the season: a bloody visceral Macbeth populated with virile, vibrant players trying to navigate an environment as Stygian in lighting and atmosphere as it is inside their souls.

If you have seen better Macbeths, this one helmed by Festival Artistic Director Antoni Cimolino earns a page in your memory book as a compelling descent into the heart of darkness. As much as anything we saw, this was the production that slipped perfectly into Stratford’s mission of making these 400-year-old works as vital and lucid as possible.

The performances were muscular and sensual with Ian Lake depicting a cross between a sweaty, begrimed Fabio and an instinctive military field commander. Krystin Pellerin delivers the voraciously ambitious enabler Lady M with a decidedly sensual kick. When she washes the dirt and blood off Mr. M’s body at his homecoming, the frigid heath heats up considerably.

Lake’s newly-named Thane of Cawdor is never a bloodthirsty monster nor a stunning intellect. But he’s no blameless protagonist either. He is surprised at the unexpected temptations promised him, then intrigued when the first laurel arrives, then enticed by his wife’s vision of a crown. But once he is seduced by inexcusable greed, he becomes a full passionate partner in the infamy once King Duncan is murdered.

Pellerin is a bit too much of English rose to convince you that she harbors a curdled soul sheathed in steel. But her ambition is so carnally seductive that you’d be killing kings, too, if she asked you.

As always, the attention to detail is stunning such as the war-worn garb and swords still stained with blood. Scene changes are effectively achieved by a few pieces of battered furniture, a wizardly morphing array of lights and an enveloping soundscape.

But the joy is hearing Shakespeare’s language spoken with a polish that, once again, preserves the lyricism along with a clearly communicated sense of the words. Everyone connected to the production in every role and every capacity has dissected each moment and devised ways to communicate its sense to the audience. It is the glory of the company that they let forth so fluidly with the verbiage, finding the right cadence for music and meaning.

All My Sons

Many Canadians feel, as fellow residents of the continent, that they ought to be considered “Americans.” But this production of Arthur Miller’s first Broadway success is a very Canadian take that works well on its own merits but is missing the sense of post-war small town “America” as we folks south of the border perceive it in our constructed mythology.

It would be nearly impossible to describe what is absent; it’s something in our DNA resulting from two and half centuries of drinking from the same literal and metaphorical well. Otherwise, this effort helmed by Stratford grande dame Martha Henry is satisfying for its fine performances and its merciless indictment of people who value commercial success over community responsibility. Still, Stratford’s vision is not really late-1940s Ohio – something that Palm Beach Dramaworks’ fine production in 2011 nailed to the clapboard wall.

Miller traces a long day’s journey into night for the Keller family and their neighbors. Patriarch industrialist Joe has been exonerated of knowingly shipping defective airplane parts to the military during the war. But his partner and neighbor was convicted in the scandal, which cost the lives of several airmen.

The Keller family still mourns the disappearance in action of one son. But now, years later, the mother Kate still genuinely refuses to believe he is dead, common sense to the contrary. Fatal secrets threaten to unearth themselves today with the re-appearance of the imprisoned partner’s daughter who wants romance with Joe’s surviving son, and the crisis is aggravated by the return of her angry brother who believes Joe is really guilty.

Other productions have given appropriate weight to the domestic drama as Henry does, but this director’s edition deftly hammers that we all have a responsibility to each other in society. In Henry’s vision, the overarching theme is the tragedy in the heedless pursuit of the American Dream (shades of the soon-to-arrive Death of a Salesman) that comes at the expense of the protagonist’s humanity.

Henry and company provide so much else to savor, especially the performance of Stratford veteran Lucy Peacock as the mother. Her grief persists with a profundity that threatens to cross over from neurosis to psychosis. Usually Kate’s obstinacy is hard for the audience to buy. Peacock’s achievement is her ability to convincingly deliver a mother so deep into a fantasy obsession that it can deflect facts.

The production started a bit slowly, but that is precisely the way Miller wrote it, easing us into a recognizable environment of everyday characters we not only can related to, but identify with. It also allows the complex backstory to be unobtrusively feathered in.

Performed with a minimum of scenery, Henry has opted for “colour-blind casting” in which the family next door – Joe’s partner and fall guy — are African Americans. In playbill notes, Henry says she started out intending the casting simply to use the considerable talents of Sarah Afful as the daughter. But Henry then decided that there was nothing unusual about positing that a white middle class family in a small town in middle America would have a black family as business partners, bosom buddies and close neighbors.

The cross-ethnic element stokes the ongoing dispute whether theatrical illusion is unfairly stressed if the audience needs so much mental gymnastics that they are drawn out of the play. Frequent visitors to Stratford, on this continent and across the ocean, have become accustomed to color-blind casting being as normal a theatricalized convention as characters breaking into song in a musical. But in this country, it’s more of a struggle to buy in naturalistic plays such as black families owning a Southern plantation in the James Earl Jones’ Cat On A Hot Tin Roof on Broadway in 2008. Yet it does not seem as odd in classical theater: In Stratford’s Breath of Kings, an African-American played Prince Hal with short dreds and it didn’t distract the audience. The debate continues.

A Chorus Line

Confession: I’ve seen nearly a dozen productions of this show and enjoyed almost all of them. But I was in no hurry to see it again because the licensing company insists that almost everything mirror the original Michael Bennett-Bob Avian staging. So if you’ve seen it two or three times, well, you’ve seen it two or three times.

But director Donna Feore won hard-lobbied permission to reinvent the piece for the Festival’s thrust stage. Thank goodness and Bennett’s executor John Breglio. This is A Chorus Line reborn with a blinding energy and luminous inventiveness that would likely enchant Bennett. Feore brings everything out from the proscenium and into the audience’s lap. Her mostly original choreography is executed by a shining cast of triple-threat crease-sharp performers who rip the stories out of their marrow. Again, by virtue of reinvention, Stratford has created a version that owes little to any you’ve seen before.

Members of the company in A Chorus Line.

Feore has preserved, of course, iconic images such as the dancers standing “on the line” and Cassie leaping in front of the mirror. But the fabled line is at the back wall of the thrust stage. When someone comes forward to tell their story, they move out of the corps and straight to the audience. In numbers like “At The Ballet,” Feore’s choreography brings the swirling images downstage, whirling around the singers. The ensemble envelops them and the audience in the characters’ memories.

The talent of the singing-dancing-acting performers is peerless. While a few stand out, Feore has melded them and their characters into a community of professionals who know what each other’s lives are like. When someone tells their story, the others are clearly listening intently and nodding in affirmation of the resonating tale.

The pizzazz and proficiency of the performers and director-choreographer are matched by the large hidden orchestra who push a tsunami wall of sound from the first notes following “a five-six-seven-eight.” The same goes for the design and execution of the technical facets, especially the more than 700 light cues. Additionally, the clarity, distinctiveness and balance of the sound may be the best I’ve heard in any musical anywhere.

Stratford administrators have withstood grief from some long-time patrons for condescending to program popular musicals into the schedules. But so long as they can produce something like this revival of the classic American musical, they should be encouraged not criticized.

Shakespeare In Love

Shakespeare’s stage work often has been translated to film, but it’s rare that an original Shakespearean-inspired film is transferred to the boards. Yet Lee Hall, the writer behind Billy Elliott and The Pitmen Painters, was seduced by the opportunity to turn the 1998 film Shakespeare in Love into a stage play.

The effort, which was produced by Disney Theatricals in London two years ago, has enchanted audiences at Stratford this summer as a gentle romantic lark with a mild sense of wry humor and a well-calculated campaign to charm the groundlings. On its own merits, it’s a mildly entertaining farce.

But it’s not even a shade as witty, incisive, nimble, romantic, sensual or moving as the banquet of a film. Hall is a fan of the original screenwriter, the legendary playwright Tom Stoppard who heavily doctored the original screenplay by Marc Norman. But so many of the film’s virtues are missing: alchemically charismatic lead actors, a delightfully manic pace, and especially the dense accumulation of inside jokes and references about theater, Shakespeare life’s and his works.

Luke Humphrey as Will Shakespeare with members of the company in Shakespeare in Love. Photography by David Hou.

Hall kept the basic structure tracking the young writer as he clumsily pens Romeo and Ethel The Pirate’s Daughter and who has a career-inspiring but doomed affair with a young woman in love with theater. But Hall’s comedy is far broader, the romance is less lusty, the fabric of Shakespearean references is thinner and there’s a lot more Marlowe than in the film which pulls focus. The play seeks to be more of a crowd-pleaser than the film, which melded hearty comedy with an intelligent and passionate love letter to theater.

It also inserts every opportunity to throw in live music from period instruments like recorders and lute, not to mention madrigal chorales – none of which advances or even embroiders the forward narrative drive.

But Hall is an experienced hand at entertaining an audience. He both understands effective dramaturgical construction as well as knows when to have a much-talked about dog skip across the stage and have someone remark drily, “Out, damn Spot.”

The ensemble, as always playing multiple parts, was led by Shannon Taylor as Viola, lovely but not as luminous as Gwyneth Paltrow, and Luke Humphrey as Will, handsome but more of a hapless farmboy come to town than the steamy genius-in-the-making created by Joseph Fiennes.

The production appears to duplicate the London production with the same director, Declan Donnellan, designer Nick Omerod, choreographer Jane Gibson and composer of incidental music Paddy Gibson. You can’t escape the sense that this is just another step toward Disney taking it to Broadway, but I wouldn’t bet on its survival without a strong rewrite.

The result is nothing to be ashamed of for anyone on either side of the footlights; there are plenty of laughs. But it’s telling that the swelling emotions prompted by the final scenes of the film are absent and that’s a shame.

A Little Night Music

Sometimes the urge to reinterpret can shunt a work off the rails. Director Gary Griffin of the Chicago Shakespeare Theatre seems determined to put a fresh spin on this Stephen Sondheim/Hugh Wheeler masterpiece whether it’s in the spirit of the moonlit gem or not.

He has cast gorgeous singers garbed in glorious costumes, but made several baffling choices. For instance, the first act takes place amid a forest of industrial smokestacks. The second act on the Armfeldt grounds is overwhelmed by a two-story high golden gate so interwoven in convoluted filigree that its distracts from everything in front of it as if this was a grand opera.

Members of the company in A Little Night Music. Photography by David Hou.

Continuing with the bent for cross-ethnicity casting, the aging diva Desiree is played by an African-American, her daughter by an Asian-American and her mother by a white bread Canadian. With a little work, you can accept much of the casting, but sometimes it takes too much of an effort. For instance, Yanna McIntosh’s Desiree has a lovely voice but one that sounds as if it originated no closer to Stockholm than the Svenska Deli on the Loop in Chicago, let alone the European continent. Audra McDonald, for instance, easily would have persuaded you that she was a world-weary actress who had played the provinces of Scandinavia.

The casting of Ms. McIntosh in the lead is puzzling since the beloved leading lady of Stratford musicals, Cynthia Dale, is relegated to the secondary part of the caustic cuckold Charlotte Malcolm – a role she plays perfectly, but you yearn to have seen her play Desiree, a part she was born for.

As Desiree’s once and future lover, the Fredrik Egerman here is not a once-dashing man about town, but a nebbishy blunt lawyer most likely writing mortgages than mesmerizing juries with final summations. He’s certainly no one who would have attracted Desiree even a couple of decades earlier.

Besides Dale, the outstanding performance is that of Sara Farb as the lusty maid Petra, the sole purveyor of passion in the entire show. Her every entrance ratchets up the electricity on stage and her rendition of “The Miller’s Son” is as evocative as any predecessor we’ve seen channeling a young woman who can already see her future decades hence.

Over and over, Griffin seems obstinately determined to deconstruct the show. His pace is not so much elegant but frustratingly languid. The comedy is more farcical than witty. The whole undertaking may have sparkling costumes of beaded gowns and formal wear, but it lacks the crucial aura of people in late maturity ruing “what fools we mortals be” as their lives are being eclipsed by time and as they realize some hard-won lessons of wisdom. The atmosphere of Ingmar Bergman’s film Smiles of a Summer Night seems curiously absent.

What redeems the evening is how perfectly musical director Franklin Brasz and his 19-member orchestra render Sondheim’s brilliant score in various forms of three-quarter time. The music is played with a lushness and freedom that enchants the audience. He and Griffin apparently agreed to slow down the tempi so that while numbers lag a bit, they allow the singers to enunciate with crystalline clarity and enable the audience to savor Sondheim’s brilliant lyrics.

As You Like It

If there ever was a textbook example of the Festival’s commitment to reassuring everyone that the Bard can be a hoot, this umpteenth edition of As You Like It certainly qualifies.

It’s not simply bookending the play with joyously rowdy Newfoundlanders at a drunken celebration in the 1980s. It’s not only that director Jillian Keiley and company maintain a manic pace with more bits of comic business than an all-day Marx Brothers-Three Stooges Festival.

It’s taking audience participation to delightful extremes. If you don’t enjoy yourself, it’s your own fault. You’re just an uptight stick-in-the-mud.

Most everyone is given a bag with mysterious items whose use only becomes clear as the show progresses. At promptings from Hymen, here promoted to glam female emcee, you hold up a snatch of pine tree to create an auditorium-wide swath of Arden Forest. Denizens of the balcony create a night sky by holding up stars. Creatures running through the forest are props handed off in a stadium wave across the orchestra seats. Everyone is enlisted in singing in a round led by Hymen. A few are drafted on stage for the final wedding scene and ensuing folk dancing.

Imagination runs riot as Keiley and friends proudly adorn the many multiple plot threads with daffy analogs to the 1980s. One character shows off his intelligence by finishing a Rubik’s Cube puzzle while giving a speech. The Greek wrestling match is staged as an All-Star Wrestlemania bout. The retreat in the forest is basically a hippie commune. It all sounds a bit precious, but the enthusiasm of the cast is infectious and winning.

The acting is perfectly serviceable if not outstanding, including cross-gender opportunities for Stratford vets Brigit Wilson as Duchess Senior (an ousted CEO) and Seana McKenna as Jaques (here a nature photographer).

Okay, it does get to be a bit much sometimes. Keiley has festooned the proceedings with so much comedy racing at such a clip that the verbiage gets lost even when it’s delivered by such expert hands. But doubtless, Will would raise a tankard in appreciation of what these clowns have wrought.

The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe

This new adaptation of C.S. Lewis’ classic fantasy fable is a lesson in how to produce excellent children’s theater that occasionally entertains the chaperones as well.

The talent, resourcefulness and imagination that the company lavishes on its other efforts is equally evident here. While it may not have the budget of Macbeth, this combination of committed acting, inventive staging, special effects, nimble lighting, digital projections on a curved scrim, evocative costumes, original music and puppetry is as compelling in its modest way as an amalgamation of The Lion King and Warhorse.

Members of the company in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. Photography by David Hou.

The cast is a mix of experienced professionals and conservatory students playing multiple roles in this compact but magical retelling of four children escaping World War II Britain through a portal to face down an evil queen in a magical land. Lewis’s heroes’ journey mixed pure fantasy with subtle messages of fascist tyranny and Christian tenets.

Adrian Mitchell’s script is filled with all the key narrative scenes ingeniously realized by director Tim Carroll and a creative team that plugs into the imagination of both the children in the audience and the adults. Mitchell tries to mollify the adults by dropping in a score of subtler verbal and visual jokes such as a reference to “Fifty Shades of Fur” and cross-generational plugs such as “How to Train Your Unicorn.”

The production values and resourcefulness peak when the giant lion Aslan appears. A Warhorse-like creation, Aslan speaks with a warm paternal growl, paws the ground, seems to be breathing and comes to thoroughly convincing life, even though we can see the operators inside a framework whose hide are the covers of famous children’s books.

If you go to Stratford primarily to see Macbeth or something similarly highbrow, you can pass this up. But if you have a free slot in your schedule, you won’t be disappointed by this fairy tale.

Michael Blake as Macduff (left) and Ian Lake as Macbeth in Macbeth. Photography by David Hou.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design