By Bill Hirschman

By Bill Hirschman

What theater does better than any other art form is depict close-up the devastating pain when deep emotional wounds inflicted decades earlier are ripped open again. And it depicts the process of rending apart the psychic scab in unforgiving real time with no merciful quick cuts or arty montages.

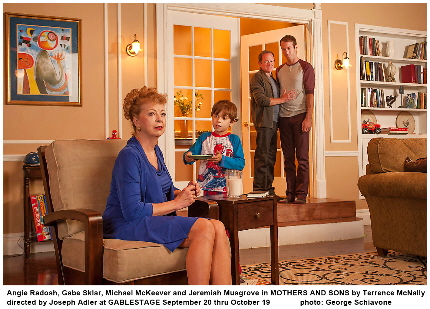

That’s what GableStage’s production of Terrence McNally’s script Mothers And Sons does even better than last spring’s world premiere on Broadway: Depict the terrible cost that the protagonists have kept sealed up for two decades, now flowing forth.

The New York version was superb because it brilliantly underscored how differently four generations of Americans have, are and will someday view life as a homosexual — plus a benchmark performance by Tyne Daly as a homophobic patrician.

But where the Broadway characters repressed their suffering throughout and learned only a little, GableStage director Joseph Adler and his cast have deepened the experience by gradually excavating the depths of the anguish without sinking into self-pitying bathos. The protagonists markedly grow in self-awareness.

Everyone here is at the top of their game from Adler’s pitch perfect guidance to the paste-it-in-your-scrapbook performances of Angie Radosh, Michael McKeever and Jeremiah Musgrove.

The play opens in a well-appointed apartment on the Upper West Side. A handsome middle-aged man and an older matron wrapped in a mink coat like armor are staring out at a view of Central Park. They are extremely uncomfortable with where they are and in being in each other’s company, although we don’t know why.

Cal (McKeever) is a 50-ish money manager who had a passionate six-year relationship with Andre, the son of the woman, Katharine (Radosh). But Andre died of AIDS 20 years ago and other than attending a memorial, they have had virtually no contact.

Eight years after Andre’s death, Cal fell in love with Will (Musgrove), a writer 15 years his junior. The two married and now have a 6-year-old son, Bud (alternately Gable Sklar and Max Leifman).

With no warning after a two-decade silence, Katharine has arrived ostensibly to return Andre’s diary that Cal had sent her – a volume neither has read. Katharine is a New York suburbanite who had moved with her husband to Dallas where she raised Andre. A key triumph of McNally, Adler and Radosh is that while their Katharine cannot comprehend something as distasteful and alien as homosexuality, she is not a saliva-slobbering hate-mongering bigot – just a hardened representative of the mainstream mindset of a certain period.

Recently widowed by a husband she didn’t love and facing a bleak sere life ahead, Katharine is really here to find someone to blame for her son’s death and even for his “turning gay.” McNally wisely does not blame her coldness for either, but clearly her remoteness contributed to Andre’s leaving home – something she subconsciously suspects but will not admit to herself.

The depth of her disaffection is seen as she sarcastically characterizes what she assumes is Cal’s vision of her.

Katharine: That I’m a terrible woman. Men are noble, good. Men are to be loved. Women – especially mothers – are evil, cunning, vile even. Pity the young man who has a mother such as Andre’s. He was doomed to a life of AIDS.

Cal: This is unspeakable. I hoped you’d let Andre go. That some part of you had accepted our loss.

Katharine: It will never be “our” loss. You lost a man and quickly found other men. I lost a son.

Cal: I’m sorry, I will always be sorry.

Katharine: Not good enough. The two of you, this fancy apartment, a child of your own who will no doubt grow up to cure cancer and take the men’s title at Wimbledon. Any mother would be proud to have a son like that. I’ll order another one myself. How much do they cost? What other tangible evidence of happiness haven’t you shown me yet? Why did your life get better after Andre and mine got worse? Why haven’t you been punished?

Katharine accuses Cal of giving Andre AIDS. Cal has to tell her, with some pain, that Andre contracted the virus when he was unfaithful to Cal.

As she and Cal wrestle with Andre’s death and sexuality, Katharine must face that the warm and nurturing life that Cal, Will and Bud have built is precisely what she never had, likely due to her own faults.

Again, one of the script’s virtues is how each character’s chronological age tracks American society’s evolution of attitudes toward homosexuality and, in Bud, the potential of a future so absent a stigma that it may not even be part of the daily math of living.

Cal tells Katharine: “But he wasn’t faithful either. Monogamous. Of course we’d never taken marriage vows. We weren’t allowed to. It wasn’t even a possibility.

Relationships like mine and Andre’s weren’t supposed to last. We didn’t deserve the dignity of marriage. Maybe that’s why AIDS happened.”

Conversely, Will may as well be from another planet sociologically. Cal tells Katharine that parenting “comes a little more naturally to Will than me. I think it’s generational. I never expected to be a father. He never expected not to be one.”

The generation gap is underscored by Will, who can only see the AIDS crisis through his husband’s eyes. He tells Katharine:

“I try to imagine what those years were like for him and Andre but I don’t get very far. Maybe I don’t want to. The mind shuts down – or the capacity to care. It’s one way of dealing with it…. ‘What Happened to Gay Men in the Final Decades of the 20th Century.’ First it will be a chapter in a history book, then a paragraph, then a footnote. People will shake their heads and say ‘What a terrible thing, how sad.’ It’s already started to happen. I can feel it happening. All the raw edges of pain dulled, deadened, drained away.”

It also portrays the evolution of the attitudes of men in late middle age and older who have had to come terms with the tragedy. Katharine says if she ever discovered who infected Andre, she’d kill him. But Cal recalls that the desire for revenge was dwarfed by the ubiquitous tragedy:

“I was in enough pain of my own. Andre was dying, I couldn’t save him. Everyone was dying. I couldn’t save any of them. Nothing could. Something was killing us. Something ugly. Everyone talked about it but no one did anything. What would killing one another have accomplished? There was so much fear and anger in the face of so much death and no one was helping us. There wasn’t time to hate. We learned to help each other, help each other in ways we never had before. It was the first time I ever felt a part of something, a community.”

This play does not have a traditional happy ending, but there is a rapprochement in the eventual mutual recognition that each truly loved Andre.

Radosh’s absolutely outstanding performance is not better or worse than Daly’s but different. Daly’s Katharine was a genuinely unlikeable person whose ability to love, if it ever was there, died during a 20-year deep freeze. We pity her during her recitation of past disappointments, but we don’t excuse her. By the end of the play, Daly’s Katharine is still a homophobe with little hope of changing. All she acknowledges now is the shared loss.

Radosh, too, spends much of the show with her emotions tied up or just inaccessible to her own consciousness. But Radosh alchemically makes us sympathize with Katharine’s loneliness and lack of connection even as we know she has inflicted much of it herself. We can see Katharine’s pain just below the carefully-applied makeup and tightly-controlled smile because the sorrow seeps out of Radosh’s eyes and echoes in her tight dry voice. That makes her angst credible as bits of her psychological backstory slip out in anguished revelations. The suffering that Daly successfully refused to expose is what Radosh so convincingly lets slip out of Katharine under the volcanic pressure of her interactions with Cal.

McKeever spends the first half exuding his trademark geniality as Cal’s natural politeness and compassion under pressure prevail over Cal’s banked anger and resentment at the woman he believes had emotionally blighted the man he loved. McKeever has shown this side of his acting skill set many times in light comedies. But as we saw last season in his concentration camp denizen in The Timekeepers, McKeever is an equally capable virtuoso at strategically pulling emotions out of his spleen.

Eventually, Cal cannot withstand Katharine’s poorly veiled blame and McKeever (unlike Broadway’s phlegmatic Frederick Weller) erupts with the passion that Cal thought he had successfully expunged when in actuality he had only locked it away. His repressed anger as expressed by McKeever is heart-rending.

McKeever and Radosh give their characters an oil and water chemistry illustrated by their flinty banter and underscored in that Radosh is nearly a head taller than McKeever. They give their characters armoring personas because if either succeeds in touching the other’s heart, they fear their hard-won homeostasis will disintegrate.

Musgrove skillfully creates a 21st century denizen with an up-to-the-minute attitude. Musgrove’s Will sees no more reason to put up with homophobia any more than a black man would put with overt racism. To Will, it’s not just “Haven’t we gotten past this nonsense?,” it’s an observation no more remarkable than the sun rises daily that such prejudice is no longer acceptable. Musgrove’s Will only maintains a limited civility in deference to his husband’s feelings.

Young master Sklar is appropriately winsome in his non-judgmental directness and inquisitiveness that reflects a mental health we can only wish we could preserve as we get older.

Of course, these performances result in large part due to the emotional choreography of Adler at his best. He and his company have created a moving and illuminating evening writ large in letters of fiery pain and tear-stained regret.

(Full disclosure: McKeever is a co-host with me on Iris Acker’s Spotlight On The Arts television program on BCON.)

Mothers And Sons runs through Oct. 19 at GableStage, 1200 Anastasia Ave., Coral Gables, inside the Biltmore Hotel. Performances 8 p.m. Thursday-Saturday, and 2 p.m. & 7 p.m. Sunday. But no performances Thursday Sept. 25 or Friday Oct. 3. Instead, added performances 8 p.m. Wednesday, Sept. 24 and Wednesday, Oct. with reduced price to $30. Runs 90 minutes, no intermission. Tickets $40 – $55. For tickets and more information, call 305-445-1119 or visit GableStage.org

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design