Florida Grand Opera’s production of The Passenger / Photos by Brittany Mazzurco-Muscato

By Bill Hirschman

After five years of reviewing the Florida Grand Opera, it’s time to acknowledge a dirty little secret: I’ve admired many technically thrilling productions, been amazed by the artistry of wildly emoting divas. But these tales of starving Bohemians and Druid priestesses left me personally unmoved, even had me puzzled at the enduring appeal of the art form.

That is, until Saturday, when I saw FGO’s shattering production of The Passenger. Finally, I understand why opera exists and what it can be.

To drink in the infinitely lovely music, lyrical yet poetic words, deft performances and imaginative staging in service of something with recognizable relevance, to see it encompassing — yet going beyond — timeless verities of love and tragedy – all of that rewrote my understanding of what Puccini, Verdi and the rest were trying to accomplish for their contemporary audiences.

Certainly, it helps immeasurably that this story of Holocaust horrors resurfacing to haunt the guilty remains ingrained in our modern zeitgeist. But Mieczyystaw Weinberg’s score and Alexander Medvedev’s libretto based on Zofia Posmysz’s novel dig far deeper into the complex human psyche than some heartless American sailor abandoning a naive Japanese girl.

The Passenger embraces a half-dozen themes. But this production underscores humanity’ strength to live as fully as possible in direct spite of the most horrendous nightmare in which cruel and capricious death is possible, even probable at any second.

The work is a courageous continuation of the “new” FGO under General Director Susan Danis – taking huge financial risks with rarely-seen but much-discussed works (such as Marvin David Levy’s Mourning Becomes Electra) mixed in with popular warhorses.

Weinberg, a Polish émigré in Russia, wrote the opera around 1968 after his mentor, Dmitri Shostakovich, suggested he look at Posmysz’s novel. But the subject matter did not fit the Soviet government’s prejudices and Weinberg died without ever seeing it performed.

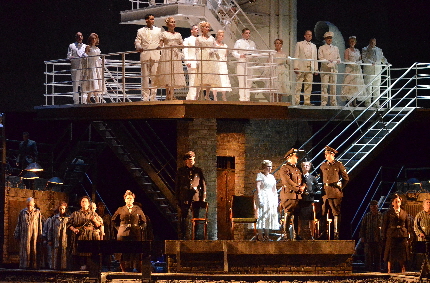

It languished until 2010 when the Bregenz Festival in Austria spent millions of dollars on a production directed by David Pountney featuring a massive two-tiered set designed and lit by Johan Engels. The reaction was electric, and the work has been mounted with many of the same performers, the same set, lighting and direction in London, New York, Chicago, Detroit, Houston and Warsaw where it will return after this production for a third visit.

This edition, too, has the same director, Engels’ monumental set and lighting, and a cast of principal singers who have appeared in previous productions, making their FGO debuts. But several performers including a huge chorus and a large orchestra under Steven Mercurio’s baton are local or FGO returnees.

The plot opens in the early 1960s as Liese (Daveda Karanas) is sailing with her diplomat husband Walter (David Danholt) to Brazil where he will serve in the German embassy. She is unnerved and unhinged when she spots a silent ghost-like woman in a heavy caul-like veil roaming the decks.

Liese admits her secret to Walter: She was an overseer in Auschwitz in her youth and she is convinced this woman Marta was a prisoner whom she thought dead. She is certain this woman would recognize and expose her.

The action flashes back to the camp where Liese is intrigued by the indomitable but vulnerable prisoner Marta (Adrienn Miksch) who compassionately nurtures her fellow inmates, trying to maintain their humanity despite the likelihood of execution. Liese is fascinated by Marta’s spirit but resents her hatred. Several of the prisoners are seen interacting, revealing their backstory, including Yvette (Elena Galvan), Krystina (Hilary Ginther), Bronka (Kathryn Day) and Katja (Anna Gorbachyova).

Liese tells Walter that she was just following orders and committed no heinous acts. But her actions in the flashbacks toward Marta are far more complicated, especially when she discovers that Marta’s fiancé, Tadesz (John Moore) who was arrested at the same time, has accidentally been reunited with Marta. Tragedies within tragedies occur, but the rationalizing Liese never acknowledges her responsibility in them, even at the final curtain.

Part of the production’s power is the audience is inserted in the same three-dimensional space with living human beings. Unlike once-removed black and white photos, grainy newsreel footage and even incisive films, this theatrically-created vision is inescapably “real.” The opening vision of tortured people in grimy stripped dresses with kerchiefs barely covering shaved heads, trudging like cattle to a line-up, is devastating. During one scene change, prisoners shovel out the ashes from the crematorium into wheelbarrows. Three SS officers blithely laughing how they wish they could exterminate millions in a day instead of just 20,000 to help achieve the Fuhrer’s goal of cleansing the world.

But balancing it out is the procession of breath-stopping plaintive passages in which the women sing Weinberg’s exquisite music and Medvedev’s transcendent lyrics ranging from dreams of what they will do when they are freed to imagining dignified ways to die, from the lovers’ recollections of their pretend wedding in a church to Marta’s final powerful prayer that none of this will be forgotten or forgiven.

It is difficult to understate the impact of the Engels’ brilliant melding of two-story set and lights, with Poutney’s vision. The top half of the passenger ship is blinding pure white as if in heaven, and below it, supporting it, always threatening to erupt is the Stygian darkness of the concentration camp with its barracks and other set pieces rolling in on train tracks like cattle cars. When the lovers meet for the first time, each is lit primarily by separate searchlights operated by storm troopers atop tall towers.

Weinberg’s music is frequently compared in tone and style to Shostakovich. What more erudite sensibilities refer to as that “Eastern European musical vocabulary of the post-World War II period” sounds a great deal like that of American symphonic composers of the 1940s and 1950s such as Leonard Bernstein, Aaron Copland and even George Gershwin– passionate, muscular, incorporating percussion, a touch of klezmer-blues, alternating vibrance with compassion.

Medvedev’s Russian libretto is performed here in a mélange of Russian, German, Polish, French, Yiddish, Czech and English representing the home countries of the prisoners. But the English supertitle translations by Karl W. Hesser prove that the lyrics are both prosaic for everyday conversation and can soar into stratospheric levels of poetry.

It would take pages to list all the justifiable praise, but the principals have some of the finest expressive voices to grace FGO’s stage, and the orchestra under Mercurio’s energetic leadership is sublime from the moody woodwinds to the martial percussion to the many-hued marimba, vibraphone and xylophone.

This chilling, harrowing and ennobling affirmation of opera as a vibrant valid art form is the don’t-miss event of this and several other seasons at FGO.

Florida Grand Opera performs The Passenger 8 p.m. Tuesday, Friday and Saturday at the Arsht Center’s Ziff Ballet Opera House, 1300 Biscayne Blvd., Miami. Tickets $19-$175; (800) 741-1010. More information at fgo.org.

To read a background feature on the opera, click here.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design