We’re back from our trip to New York to scout out productions you might want to see (or not), shows that might tour South Florida and scripts that might be worth reviving in our regional theaters. The reviews to be spread out over the holiday season are the revival of M. Butterfly, Ayad Akhtar’s new Junk, J.B. Priestley’s Time and the Conways, Anastasia, Come From Away and The Band’s Visit. Just search for “Report From New York.”

We’re back from our trip to New York to scout out productions you might want to see (or not), shows that might tour South Florida and scripts that might be worth reviving in our regional theaters. The reviews to be spread out over the holiday season are the revival of M. Butterfly, Ayad Akhtar’s new Junk, J.B. Priestley’s Time and the Conways, Anastasia, Come From Away and The Band’s Visit. Just search for “Report From New York.”

By Bill Hirschman

The tragically misconceived presumption, unspoken because it is so taken for granted, that western culture is somehow superior, more central to the universe than eastern culture, was at the core of Puccini’s Madama Butterfly and its brilliant 1988 reinvention, David Henry Hwang’s M. Butterfly.

But in Hwang’s current 21st Century revision of the Tony-winning play, it’s the wrongheadedness of that hubris that is taken for granted. This incarnation delves more deeply into the human relations of this fictionalized riff on the true story of a French diplomat who had an affair for 20 years with a Chinese opera singer, only to discover that his lover was a man spying for the government.

Hwang and director Julie Taymor seem more interested in the power struggles between the partners, the psychological gymnastics each needed to maintain the relationship, the difference between lust and love.

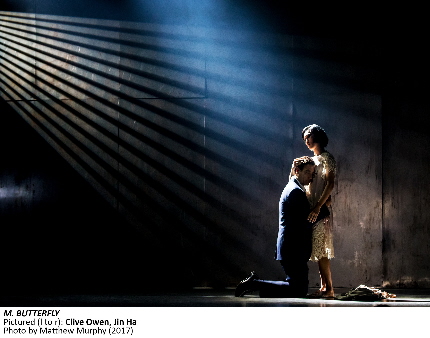

This production at the Cort Theatre benefits from film star Clive Owen as the hapless Rene Gallimard, reinforcing his props as a stage actor by inhabiting a wounded vulnerable character far different than his film personas, and also from Jin Ha making his Broadway debut with a more cynical jaded Song Liling than in some earlier incarnations.

Hwang and Taymor have indeed tweaked the script in ways that make audiences scratch their heads wondering whether the 1988 version included such and such. The most obvious is that in the original Gallimard strips naked at the end before committing suicide; here Song reveals his body – giving each scene a much different metaphorical meaning.

Taymor’s bent for visual staging suffuses this surreal, highly theatrical production, scoring both positive and negative marks. Oddly, the production’s strength is how she has elicited fine performances, including underscoring how Song is drawn deeply into the relationship until he is as invested in it as Gallimard.

Indeed, it’s the comparatively spare but showy visuals that constitute the weakest part of the evening: Much of the set is composed of awkwardly sliding stage-high silver panels that seem painted by a high school drama club. But Taymor can’t resist some spectacle and she has worked with choreographer Ma Cong to create a graceful elegant Chinese opera scene to introduce Song; then to compare how Mao’s Revolution has squashed the sensitive creative soul, she stages an extended Peoples Government-approved dance recital that goes on and on and whose dramaturgical worth could have been fulfilled in about 90 seconds.

Owen, an actor who has undertaken Pinter and Shakespeare on stage but hard-bitten men of violence on film, has unflinchingly embraced the deeply flawed Gallimard. At the opening of the play, his Gallimard imprisoned for espionage is emotionally shattered – not by the revelation of his lover’s gender, but by his lover’s betrayal. Even as the storyline reels back to the beginning of the relationship, Owen makes credible how mesmerized the hapless Gallimard is, how helpless he is in the rising tide of the affair, and nearly makes us believe his claim that he never suspected Song’s physical gender.

Jin Ha, who appeared in the original Chicago company of Hamilton and has a few professional credits out of college, is a standout. From the moment he first appears in the opera, he radiates an exotic magnetism that makes Gallimard’s initial attraction completely understandable. The original creator of the part, B.D. Wong, was almost stereotypically inscrutable whereas Ha is clearly concealing a raft of sardonic thoughts including wry sophistication, contempt and a clear knowledge that Song believes himself in control of all situations. To be fair, though, if you didn’t know Song’s secret in 1988, you easily bought the illusion that Wong’s Song could be mistaken for a woman during the early stages of the play. Ha’s Song may be effeminate, but his biological gender is never in doubt to the audience.

The pacing does get a bit poky and a little less self-indulgence by Taymor could have cut ten minutes out of the evening.

But Taymor, Hwang and company succeed in bringing the audience deep into a maelstrom of self-delusion and rationalization in extremis.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design