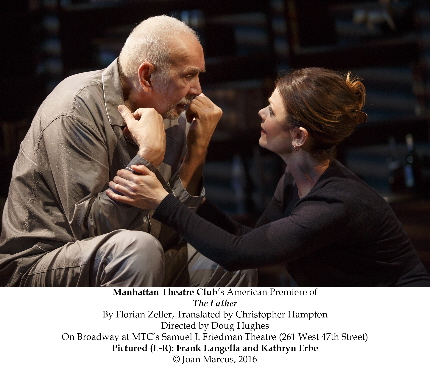

Frank Langella and Kathryn Erbe try to reach each other through the fog of dementia in The Father / Photo by Joan Marcus

We’re back from our trip to New York to scout out productions you might want to see (or not), shows that might tour South Florida and scripts that might be worth reviving in our regional theaters – many of which with elements nominated for Tony Awards. We will run our reviews intermittently over the next few weeks. The shows include: Shuffle Along, School of Rock, The Humans, The Father, Bright Star and Waitress. Links to other reviews can be found at the bottom as the reviews run.

By Bill Hirschman

As Boomers become more of the theater-going public, we see more stories about how we are becoming a nation of caretakers of parents and grandparents.

But these heartbreaking stories are told from the point of view of the younger generation agonizing about the failing health of their loved ones while quietly fretting that they are seeing at least one scenario of their own future.

But the play The Father depicts increasing dementia from a far more frightening viewpoint: from the inside.

We see the world through the eyes of the aging Andre who the audience does not initially realize is the ultimate in unreliable narrators. We believe we are seeing an objective third-party depiction of what is actually happening, who is in the room, where the room is.

In fact, over the next 90 minutes, we watch the complex, vital Andre moving from befuddledness through an inexorable tide of confusion into senility. As incarnated in a bravura performance by Frank Langella, the audience feels the terror of disorientation that Andre does as he realizes — sometimes — that his conscious perception is no longer something he can rely on.

The play at the Manhattan Theatre Club was written by Frenchman Florian Zeller and translated by Christopher Hampton whose many works include Les Liaisons Dangereuse and the translation of Yazmin Reza’s Art. While you should see it in New York for Langella’s peerless performance before the June 19 closing, you can bet a car payment that it will be produced in South Florida and around the country within a year of its closing. Local actors of a certain age should start rehearsing their audition pieces.

Andre drifts through a series of scenes in ostensibly a single room, being visited by his loving but worn-out daughter, Anne (Kathryn Erbe) who is trying to balance being a part-time caretaker with a demanding job and a personal life. It isn’t easy – Andre is innately smart, funny and barely able to accept that his memory lapses aren’t just minor inconvenient incursions of age.

But suddenly, arc lights blind the audience and we are in another scene. Some of the actions and dialogue is similar, but things are a bit different. This happens over and over. Sometimes time has elapsed between scenes, sometimes its doubles back on itself. But something is always different. Anne has a husband. No, she only has a boyfriend. This is Andre’s apartment. No, he has been living with Anne for some time. The hired nurse/counselor is one person. No, it’s another.

Each time the audience is wondering like Andre what is real in this elliptical Wonderland. Was the last scene real and is this next one just a development at a later time with a blackout of the passage of time. It takes quite a while to realize that we are simply seeing “reality” from inside Andre’s unmoored and ever-morphing perception.

This vantage point is what is so unsettling. The last time most people remember this approach being used this successfully was Arthur Kopit’s 1978 depiction of a stroke victim in Wings.

What is especially affecting is that while Andre is unnerved by the ever-changing landscape, he is less panicked than Erbe or us. Because, think about it, all of us inherently assume that what we are seeing and hearing is real, we justifiably have decades of experience trusting that our senses are communicating reality, even when we feel disoriented, we have faith that it will right itself.

Yet while Andre can be charming and witty he can be incredibly cruel. Not taking cover behind his dementia, he speaks clearly how he loves his first daughter not Anne. The very fact that he cannot censor himself invests these statements with a devastatingly unavoidable truth.

As ingenious, insightful and wryly humorous as Zeller’s script is and as brilliant as Langella’s tour de force scores, a quick look at the bare bones script also proves that a major share of the accolades are due director Doug Hughes and his design team including Scott Pask’s scenery lit by Donald Holder.

That visual element is not addressed in the script. It starts so imperceptibly that most viewers won’t catch it until the process has been underway for more than a half-hour although they will feel some unidentifiable unease. But just as Andre’s perception of events and people mutates, so does the room he exists in from scene to scene. A painting disappears, a bit of floral accessory is no longer there, furniture changes locations and eventually vanishes. This is done so subtly at first that you chalk it up to Pask establishing different locations with inexpensive alterations to the single set. But no, this underscores the breakdown of Andre’s cognition and the irising down of his life as furnishings disappear during scene changes.

Langella, now 78, has gone through so many stages of his career in almost every medium, from Albee’s lizard in Seascape to the mustache-twirling villain in a fourth-rate TV version of Zorro, from the sexiest Dracula ever seen on stage and screen, to cavorting mindlessly with Whoopi Goldberg, from Frost/Nixon to Gabriel in TV’s The Americans, on and on.

But from first to last, he has proven himself more than just a handsome charismatic performer with a self-deprecating sense of humor and a seductive sonorous baritone. He is indisputably a superbly skilled actor able to invest any worthwhile work with nuance and multiple dimension without getting caught acting. His Andre covers the gamut of human emotions without ever imposing on you the sense that you are seeing a self-conscious master class.

Langella and Hughes create an Andre who is so far down this path, yet remains so forceful and charming when he wants, so volcanic and demanding at other times that you frequently question whether full time care in a facility is the appropriate measured response.

And then Andre does something like lose complete track of time, cannot recognize people, and worst of all, has perceptions so hallucinatory that we, the objective observers but trapped inside his perceptions, have no idea what is real and what is not. Finally, he can be childlike and adrift such as when Langella emits the line “Who am I?” with a woefulness of someone terribly aware that he has lost himself.

Erbe is best known as Eames from Law & Order: Criminal Intent, but she has an extensive theater resume. The part is not especially difficult, but Erbe completely inhabits the extreme angst without ever going over the top. She masterfully weaves abiding love with the slow undeniable realization that she simply cannot continue provide the care Andre needs. Erbe’s mixture of frustration and guilt is palpable in her anguished face and strained voice.

Interestingly, since Andre believes himself relatively cogent in the early scenes (and that is what we perceive along with him), it is courageous and skillful that Erbe and Hughes credibly indicate early on that we are witnessing the middle of this process not the beginning. Like that Facebook meme “You are getting on my last nerve.” Erbe’s Anne is already at that point where she abhors the idea of putting him in a home, but she is being squeezed in a situational vise where she has little other options besides sacrificing every aspect of her future.

There is one serious problem in the New York production. Everyone except Langella is hampered by a weird aspect of the script translated by Hampton. Everyone speaks in a strange Beckett/Mamet/Pinter syntax in which people do not finish sentences. But the words do not drop off naturalistically, but end in a very affected manner. Perhaps this is intentional, perhaps it’s the actual syntax of the script, and perhaps it’s meant to unsettle the audience. What it is is distracting. This is not how Andre is hearing people, because they speak this way when he is not in earshot (unless this a dream he hallucinating). It doesn’t bother some audience members at all and irritates others like this one as unnecessary.

That aside, The Father is guaranteed to leave audience members, especially Boomers, supremely distressed.

To read our review of Waitress, click here

To read our review of Shuffle Along, click here.

To read our review of Bright Star: click here

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design