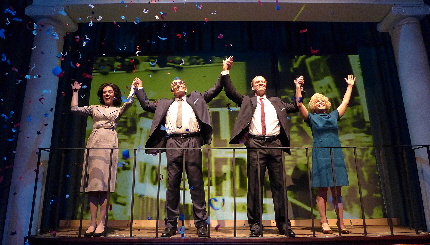

Deborah L. Sherman as Lady Bird, J. Kenneth Campbell as LBJ, Tom Wahl as Hubert Humphrey and Christina Groom as Muriel Humphrey winning election in Actors’ Playhouse’s All The Way / Photos by Alberto Romeu

By Bill Hirschman

On opening night of All The Way at Actors’ Playhouse, resonances were inescapable as the epic charting Lyndon Johnson’s expertise forging and passing the politically divisive Civil Rights Act of 1964 happened to be performed on the day that Donald Trump and Paul Ryan failed to negotiate passage of the health care bill of 2017.

Take what lessons you want about the skill set required for such a task or LBJ’s legendary abilities. But you can’t evade how Robert Schenkkan’s 2012 script has only accumulated relevance as Johnson struggles with unfortunately persistent issues such as voting rights, black lives matter, voter fraud, warrantless surveillance, homophobia, racism and, above all, coping with a deeply divided country.

The Broadway production won the Best Play Tony and a Best Actor award for Bryan Cranston in 2014, Schenkkan won the Steinberg/American Theatre Critics Association Award for best new play in 2013, and HBO filmed a version last year. So while the insider examination of how your sausage is made is incredibly dense in its depiction of warring socio-political agendas and a dizzying swirl of maneuverings, the problem is not the script.

Although the Actors’ Playhouse folks are working very hard to master this Everest of a play, this time they have barely fought the work to a standstill. The evening only catches fire intermittently, such as depicting internal disagreements among black leaders headed by Martin Luther King. But the involving tension that powered earlier editions wanes and ebbs here; it simply is not strong enough to carry this production, which clocks in at just under three hours and seems longer.

The crucial problem is that the show needs another week of rehearsal, most obviously indicated by the fact that several people don’t know their lines in this massive text. Some actors are, at best, stumbling over the rhythm of the words, and, at worst, hemming and hawing while they try to remember them.

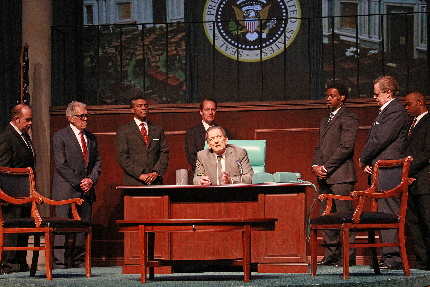

Sad to say, chief among them is J. Kenneth Campbell, saddled with the heroic task of memorizing and then owning the fluid verbosity of Johnson – a part that is probably longer than Hamlet’s.

J. Kenneth Campbell

On the other hand, Campbell with the help of director David Arisco delivers the warring facets of Johnson’s titanic character: a genuine dedication to curbing overt prejudice and poverty although he uses the word “nigra,” a vulnerable ego inside a rhinoceros hide, a lust for power, a love for the rough and tumble of politics and, above all, a brutal conscienceless pragmatism that can embrace any compromise, any tactic, any means to achieve his ends. Campbell is most effective telling tall tales about jackasses and rattlesnakes whose folksiness hides trenchant political messages.

The arc starts with Johnson becoming “an accidental President” after Kennedy’s assassination. He has one year before having to stand for election, but he is determined to pass Kennedy’s civil rights act, a cause Johnson had championed since the 1950s. It may be hard for Boomers to remember just how bitterly riven the country was, especially with Southern states (Democratic at the time like the Texan Johnson) seeing the bill as an unconstitutional incursion of states’ sovereignty.

Johnson employs every lesson learned as a veteran warrior in the Senate to wheedle, cajole, threaten, flatter and blackmail legislators. He employs arcane rules of the Senate to outmaneuver opponents. Most importantly, he makes compromises so significant (such as dropping a voting rights guarantee) that partisans question their support.

The first act ends with the eventual victory, but the second act depicts the ensuing battle to win election, counterbalanced with growing problems in the Vietnam War and the outrage over the murder of three young men signing up black voters in Mississippi.

Schenkkan clearly lays out the complex issues and political logistic challenges in an exposition-heavy script. But by the second act, the cast and the audience are a bit worn down.

What was clear on Broadway, but not as clear here, is that those aggressive tactics that boarded on admirable in the service of civil rights, now seem unnervingly callous. The candidate’s sharp abandonment of a close aide accused of soliciting a man seems heartless, even though we don’t feel the same way in the first act when he betrays his beloved mentor in the Senate.

For those with patience and focus, the maneuverings are indeed breathtaking to follow from Schenkkan, who won the 1992 Pulitzer Prize for The Kentucky Cycle and who has written a follow-up to this play, The Great Society. But on opening night, about a quarter of the audience, stuffed with free booze and food before the 8:35 p.m. curtain, did not return after intermission, which also featured an open bar.

Marckenson Charles

Most of the 17 members in the cast play double, triple and even quintuple roles. Marckenson Charles, a Carbonell-winning actor who has delivered fine work after recently returning home, is serviceable and fervent as Martin Luther King agonizing over compromises threatening to explode his coalition. But the innate depth and charisma of an icon that King exuded isn’t present and that robs the production of another source of driving power.

Some actors do solid work, such as Chaz Mena as stolid Defense Secretary Robert McNamara bringing early word of problems in Vietnam and as the unapologetically racist Sen. Jim Eastland; Jovon Jacobs as fiery Stokely Carmichael, and especially Chase Gutzmore as the impassioned Bob Moses of SNCC who gives a thundering exhortation to action at the funeral of Freedom Rider James Chaney.

But others need work. For instance, as FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, Antoni Carone, whose bio says he is “a film actor just recently started acting for theater,” needs to be reminded that on stage, you can’t drop the pitch and volume of your voice at the end of sentences because the last few words become unintelligible. Still others, fine actors of proven track records, run out of steam and focus by the second act.

Still, give credit to familiar local actors playing 40 differentiated roles including Peter Haig, Gary Marachek, Don Juan Seward II, Deborah L. Sherman, Michael Turner, Tom Wahl, Reggie Whitehead, Christina Groom, Candice Marie Singleton, Michael H. Small and Jerry Weinberg.

Arisco masterfully keeps the very talky play from seeming static by slipping scenes after each other with the smoothness of a film, and by keeping actors moving about the stage even when they are simply arguing.

Jodi Dellaventura’s set creates a political arena with cascading drapes, marble columns and wood-paneled seating banks for actors to watch the proceedings. Shaun Mitchell’s projections change the scenic background or inject newsreel footage. Some news conference scenes are projected on the back wall, captured with a live television camera.

If you make it through the marathon, the production feels ultimately rewarding, if a tough slog. But it also may elicit tears recalling a time when honest leadership accomplished altruistic service for all the citizenry of the United States.

All The Way plays through April 9 at the Actors’ Playhouse at the Miracle Theatre, 280 Miracle Mile, Coral Gables. Performances 8 p.m. Wednesday-Saturday, 3 p.m. Sunday, 2 p.m. Wednesday March 29 only. Running time just under 3 hours with a long intermission. Tickets $57-$64. The theater offers a 10 percent senior discount rate the day of performance and $15 student rush tickets 15 minutes prior to curtain with identification. Visit actorsplayhouse.org or call (305) 444-9293

To read our review of the Broadway production, click here.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design