The finale of Dreamgirls at Broward Stage Door / Some photos by Carol Kassie

By Bill Hirschman

If producers mount the musical Dreamgirls, it’s a given that they have hired as Effie some astounding young diva capable of punching a hole in the back of the auditorium with her melisma.

Indeed, Broward Stage Door has the Cat 5 voice of Sarah Gracel to headline this 35-year-old rousing examination about the interplay of fame, pop music, racism and the dangers of pursuing the American Dream. Behind her is a solid cast, skilled staging and musical direction, choreography and costumes.

All will come in for praise later, but first, a word. Elijah. As in Elijah Word. Then another word, electrifying.

Elijah Word has been shining in ensembles, musical revues and tertiary parts for a couple of years now, from Stage Door revues to the over-the-top maid/butler in MNM’s recent La Cage aux Folles. He’s hard to miss: unconventionally handsome, slender, glowing eyes, a trained dancer’s grace and most of all, topping somewhere well over six feet.

But handed the part of the outsized yet too-human “wildest man in show business” James Thunder Early, Word finally gets the role he deserves and he runs with it like a thoroughbred finally let out of the gate.

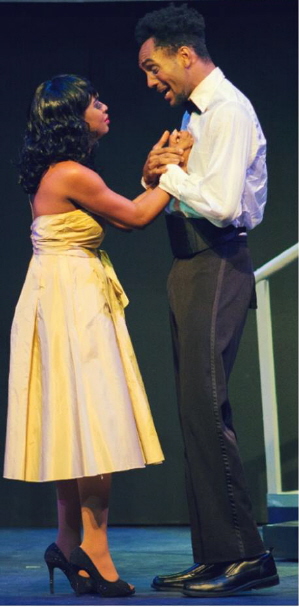

Sheena O. Murray and Elijah Word

While the role is loosely patterned on James Brown (much as the titular singing group resembles the Supremes), Word’s character is his own creation. He skips and bounds the full length of the stage in a few steps with rubber band legs. He gives the impression of being loose-limbed, but in fact, if you look closely (such as in “Steppin’ To the Dark Side”) his exacting execution is Ginzu sharp.

He throws himself unreservedly into Jimmy’s sex-drenched stage persona, but offstage Early instantly becomes the savvy veteran of too many years of backstage realities and self-preservation. Later, as his career deteriorates, Word depicts Early’s vulnerabilities and his addiction to the acclaim that performing produces.

Dreamgirls, for the unenlightened, was the 1981 hit by Tom Eyen and Henry Krieger (two white guys) that was imaginatively molded in one of the last full efforts of Michael Bennett and Bob Avian. Using a fictional trio of young women from Chicago, later dubbed the Dreams, it traces a transformative decade of pop music that reflected the social upheaval as white bread pop, R&B, soul and other genres swirled around black resistance to racism. A key element is watching how socially-conscious people who love making music are corrupted by the money and fame that had been denied them previously as African-Americans.

The score is alternately rousing and heartfelt. The lyrics are alternately straightforward and sly. The script may lack subtlety, but it is well-constructed. The end result is a work that produced a long Tony-winning first run, a fine film version in 2006 and successful tours. The best recording is a 2001 concert version with Lilias White, Audra McDonald, Heather Headley, Billy Porter and Norm Lewis.

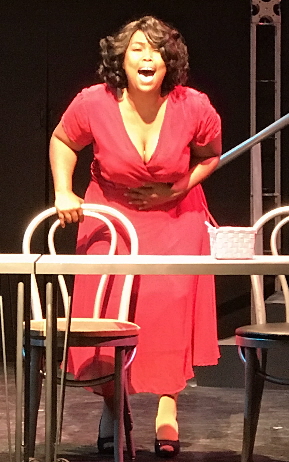

Sarah Gracel

Back to the rest of the show, Gracel is a Miamian with a few mainstream theater credits and considerable performances in other genres. But she explodes vocally here like an announcement that someone bears watching. When she sings American Idol style (think Whitney or Dionne on steroids), she seems to be pouring blood and viscera out of some wound in her aorta. Like her predecessors in the role like Jennifer Holiday and Jennifer Hudson, she’s short, plus-sized, has a round face and a child’s lips that pout through the first act and which reveal a toothy beam in the second. But that voice is like a Louis Armstrong cornet blasting a note into the heavens.

Her acting outside of the singing is just passable. She has trouble (as most young actors do) with the curse of musical theater: credibly turning a major emotional corner or depicting a life-changing decision in the space of a few seconds or a few notes. No playwright would expect that from an actor in most straight dramas.

But when she is singing, Gracel, indeed much of the cast in character, exude a visceral need for success and approval as essential as oxygen.

Don Seward (memorable in Actors’ Playhouse’s Ragtime and Sondheim on Sondheim) lends his sonorous baritone and imposing presence to Curtis Taylor Jr., the fierce huckster who initially sells Cadillacs and the Dreams’ music as pathways to revolutionize society and to carve a place of wealth and respect for African-Americans.

But the rest of the cast is admirable as well: Charisse Shields as the Diana Ross-like Deena Jones, Sheena O. Murray as Lorell, Cherise James as Michelle, Andre Russell as the songwriter C.C. White, and the talents of James White III, Sandi Stock, Jabriel Shelton, Daryl Patrice, Patrick Kolta, Richard Forbes, Stephon Duncan, Alexander Domingue, Joshua Connor, Natalie McPherson and Brettnie Blake.

The evening is shaped by Stage Door’s frequent director Kevin Black who has sculpted many of the theater’s successful revues in its recent renaissance. He’s a perfect fit for this work, which has “book” scenes, but which is primarily a propulsive succession of dramatic musical numbers in which the cast and ensemble must act passionately as they sing.

The other bold-face element is the choreography by Danny Durr. Some moves are intentional riffs on the classic routines developed for groups like the Supremes, the Four Tops and the Godfather of Soul. Some of it is classic Broadway ensemble staging. Some belongs solely to Durr. But he blends them all into a leaping kinetic pageant. The aforementioned “Steppin’ To The Dark Side” is a thrilling number as conceived by Durr and executed with sharp precision by Word, Seward, Russell and Shelton.

The sole misstep – someone probably thought this was a cute idea – was to take the ensemble depicting backup musicians and clothe them in black suits, white shirts, black ties, black fedoras and dark glasses to duplicate the Blues Brothers. It’s a cartoonish note that doesn’t match the rest of the evening.

The musical performances were overseen by James Weber who has coaxed amazing work from the cast. That said, there does not seems to be a note that he does not allow to be bent, not an opportunity for melisma that goes by. There isn’t a lot of subtlety here and, good God, it’s so unremittingly loud that the neighbors don’t have to buy tickets to enjoy it. The music is provided by digital tracks, but they are lush and rich, as they must be to put across the dynamism of the score.

The costumes designed (not rented) by Jerry Sturdevant are a parade of fashions evolving as the era changes and the heroines’ budget improves, all glitzy gowns and sharp-creased suits. The only flaw is an off-putting predilection for men wearing hats that have been sat on, punched out of shape and suffer from brim droop.

The production isn’t perfect by any means: As mentioned, the master blaster sound level and the dramatic intensity are always playing at 11 on a 10-point scale, which is impressive but gets a little wearing after more than 2 hours.

Plus Stage Door’s perpetual battle with budgetary restraints exposes itself here with a decent two-level set featuring a double staircase, tubular frameworks and numerous projections, but does not project the slick, polished feel that this musical yearns for.

That said, Dreamgirls is an exhilarating evening of scorching music.

Dreamgirls plays through Dec. 10 at the Broward Stage Door Theatre, 8036 W. Sample Road, Margate. 8 p.m. Friday-Saturday; 2 p.m. Wednesday, Saturday and Sunday; Running time 2 hours 30 minutes with one intermission. Tickets $48. Call (954) 344-7765 or visit www.stagedoortheatre.com.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design