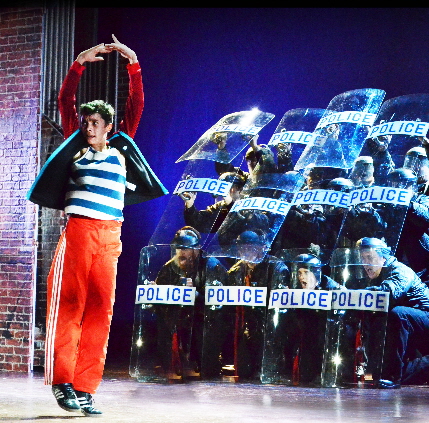

Nicholas Dantes as the hero in Billy Elliot at the Maltz / Photos by Alicia Donelan and Jen Vasbinder

By Bill Hirschman

Joy suffuses most dancers and athletes upon discovering that their body will do what they tell it to, that brain and muscles and heart and spirit meld into a whole completely in control, capable of a precision pirouette or an over-the-fence home run, a celebration of a perfection found nowhere else in anyone’s lives.

One of the most moving images in the Maltz Jupiter Theatre’s winning production of Billy Elliot the Musical is Nicholas Dantes’ euphoric face as the titular hero discovers to his growing surprise that he has a facility for making his body dance. His realization of fulfillment and self-worth that he never thought possible stirs something in the audience’s soul as we vicariously savor what we have experienced or longed to have experienced.

It overlaps and reinforces a half-dozen other themes of the Disney variety of “be who you are” and “be all you can be” – all legitimate even affecting if standard sentiments approaching meme status.

But by focusing on those elements, the Maltz has successfully re-imagined the 2008 Broadway show, which divided audiences into rabid fans and those just pleasantly entertained for a couple of hours. This new version is more effective than the national company that toured South Florida a few seasons back.

Some iconic elements of the original vision only have been tweaked because anyone who saw the musical in London, New York or on tour would have been disappointed if they had been reinvented too radically: Billy’s banging up against the clear plastic riot shields of the policemen and the transcendent aerial pas de deux in his imagination to Swan Lake with the dream image of the man he hopes to become.

Otherwise, director Matt Lenz (the Maltz’s The Foreigner), choreographer Greg Graham and the rest of the Maltz’s top-notch team have reworked the piece so that it will seem fresh to those who have seen it before. It boasts new scenic design, lighting design, sound design, new costumes and a 37-member cast. Thirty-seven.

The basic show starts from a strong score by Elton John (far superior to his Aida) with Martin Koch’s orchestrations, insightful lyrics by Lee Hall, and a first-rate script by Hall who also penned the screenplay for the much different 2000 film based on his own play. All of them trace how a 12-year-old blue collar boy stumbles into a talent for dance, running counter to the hardscrabble life of his mining community disintegrating in Margaret Thatcher’s 1984. (1984! I just got that, Mr. Orwell).

My recollection of Stephen Daldry’s film was that even with some fantastical elements, the style was mostly naturalistic. That was crucial to ensure that Billy’s impossible dream is out of sync with the depressed community struggling with the anti-union movement that led to street violence between police and miners in a nationwide strike. It also underscored how Billy needed to escape the hopeless dead-end future the community offered.

But the musical is more of, well, a musical, down to the jolly old entertainment numbers such as when Billy and his closeted friend dress up in women’s clothes before performing a full-on buck-and-wing music hall tap dancing number.

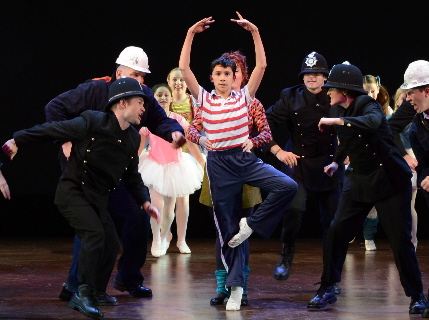

In fact, the musical, especially in this Maltz production, is a weird hybrid of styles: the soul-crushing social and political background, which is never given short shrift, the big Broadway production numbers and then the fantasy sequences such as “Solidarity” as repressive police, angry miners and Billy’s all-girl ballet class mix and match in a big dance number. The sight of the cops and the mineworkers paired up in gracefully executed pas de deuxs is, indeed, a hoot.

Theoretically, these should not (and don’t always) sit well together in the same show. But somehow, Lenz manages to keep them from seeming distractingly irreconcilable. The unspoken rationale is that the entire show is being refracted through Billy’s adolescent and imaginative perception.

Lenz gets terrific performances from his cast who never ever coast and he stages the show with a cinematic smoothness; even in the quiet moments, the forward motion never lags.

He also embraces tracing the inverse mirror arcs of Billy’s artistic emergence with the tragic destruction of his family’s way of life. To wit, the show opens with an exuberant declaration of the strike in which the miners exude certainty of their success and a pride in expressing their independence. By the end, they have not only capitulated to Thatcher’s terms but they know that their acquiescence means the end of their world. Lenz carefully charts the morphing tones as the narrative evolves.

Graham does exactly the same thing with associate choreographer Lindsay Bell. He creates his own vision within the choreographic requirements that anyone including Tony winner Peter Darling had to use by the dictates of the script such as the frenetic, manic expression of anger in the first act closing number.

Obviously, this show requires a first-rate Billy. The Maltz wisely hired the engaging Dantes, who, at 14, actually only has a few years of professional dance experience, but who has done the show twice before with different choreography.

A bit taller than some of his predecessors and quite wiry, Dantes obviously has the requisite chops to do ballet, tap, interpretative dance, a bit of rock. But he invests all of them, as well as his singing and book scenes, with a credibility that never rings false. With Lenz’s leadership, his Billy can be wistful as he tries to cope with the loss of his mother or pugnacious as any blue collar street kid. He is believable exploding with frustration in the knife-sharp yet seemingly undisciplined “Angry Dance” or the smooth Swan Lake dream sequence in which his weightless body flies in the air. (Dantes alternates with Jamie Mann. Broadway usually had three in rotation.)

Leslie Becker is another one of those stage vets who nail every scene they’re in. Her blowsy, burned-out ballet teacher with a hip flask and ciggy, Mrs. Wilkinson, is a classic creation along the lines of a heart-of-gold in a rusted iron fist. Sort of a sympathetic Miss Hannigan. You might wish for just a shade more emphasis on the woman who clearly once wanted to be a famous dancer but who lacked the talent or opportunity that Billy has. She does deliver precisely what Lenz and Graham want in the early production number with her students, “Expressing Yourself,” but it’s the perfect example of a self-indulgent showstopper that really clashes with the rest of the show.

Just as fine is Joe Cassidy as Billy’s father struggling to be a leader of his community in crisis and a single dad coping with a radicalized older son and a younger boy going in directions he can’t quite fathom.

But perhaps our favorite performance is by Elizabeth Dimon as the increasingly senile grandmother. Dimon invests a third humanizing dimension to what is written as a cartoon character. Especially memorable is when we either dip into her mind or Billy’s imagination as grandma chucks her shawl and 50 years in the song “We’d Go Dancing.” Dimon’s gorgeous singing voice channeled through her acting skills makes plausible this strange mashup of a bawdy, raucous beer hall song which actually is a regretful lament about how she knows she wasted her life by following the straightjacket social norm of marrying young.

But perhaps our favorite performance is by Elizabeth Dimon as the increasingly senile grandmother. Dimon invests a third humanizing dimension to what is written as a cartoon character. Especially memorable is when we either dip into her mind or Billy’s imagination as grandma chucks her shawl and 50 years in the song “We’d Go Dancing.” Dimon’s gorgeous singing voice channeled through her acting skills makes plausible this strange mashup of a bawdy, raucous beer hall song which actually is a regretful lament about how she knows she wasted her life by following the straightjacket social norm of marrying young.

The show is packed with terrific performers including the sonorous Jacob Smith as Big Davey with the red beard, Chris O’Connor’s union steward, Graydon Long’s impassioned radicalized son, Shane Treloar’s gay buddy and Jay Johnson’s hilarious accompanist. Plus a special shoutout is due Waldemar Quinones-Villanueva whose breathtaking grace and accomplished polish in the dream pas de deux as the Older Billy, intentionally or not, shows how far Young Billy still has to go. Much of the ensemble of kids are local, although most of the other cast members flew in.

Dialect coach Jennifer Burke has done an admirable job instilling consistent and authentic sounding thick accents in much of the cast. Even so, much of the time the cast’s enunciation is relatively clear – although not always, and one little girl was incomprehensible all night long.

Musical director Ana Flavia Zuim expertly molded the vocal performances and led the nine-piece band capable of delivering a folk song or a bright brassy showtune.

Blunt and beautiful with uplifting sentiments and a sh–load of blue language, the Maltz’s Billy Elliot is, at a minimum for some patrons, a thoroughly entertaining evening and, at best for others, a moving experience.

Billy Elliot runs through Dec. 20 at the Maltz Jupiter Theatre, 1001 E. Indiantown Road in Jupiter. Performances at 7:30 p.m. Tuesday-Friday, 8 p.m. Saturday, 2 p.m. Wednesday, Saturday and Sunday with exceptions. Running time: 2 hours 30 minutes including one intermission. Tickets are $55-$80, available by calling (561) 575-2223 or visit jupitertheatre.or

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design

One Response to Maltz’s Reimagined Billy Elliot Flies Like The Spirit Of Its Hero