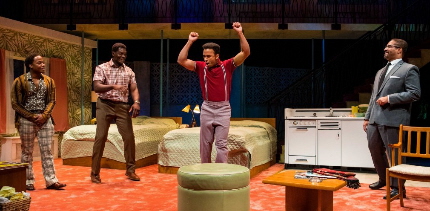

Leon Thomas III as Sam Cooke, Esau Prichett as Jim Brown, Kieron Anthony as Cassius Clay and Jason Declane as Malcolm X celebrating Clay’s championship victory in One Night In Miami from Miami New Drama

By Bill Hirschman

In 1964, the Civil Rights Movement filled the nightly news with footage of sit-ins, protest marches, violent confrontations with armed men in uniforms and hoods – indelible images that defined the moment then and to the present day.

But there were other less visual efforts to awake America to racial injustice and to demand equity – efforts by high-profile figures who chose other avenues to battle for change.

The insightful examination in the play One Night in Miami from Miami New Drama depicts four different approaches used by four African-American icons.

Kemp Powers’ 2013 script imagines the behind-closed-doors confluence of a real event in February 1964 when activist Malcolm X, singer-writer Sam Cooke, football star Jim Brown and the young man then known as Cassius Clay met in a Miami motel in the hours after Clay defeated Sonny Liston for the world heavyweight championship.

The four friends, reflecting real-life relationships, will joust, debate, proselytize and argue the merits of their strategies — sometimes good-naturedly with considerable verbal and physical horseplay, others times with heated passion. One Night in Miami isn’t so much about the boldface names, although we get a ton of biographical backstory about where they are in their lives, how they got here and how that shaped these philosophies.

Powers’ aim doesn’t seem to be endorsing or criticizing ideas either so much as putting each under the cross-examination of competing and conflicting visions. As directed by Carl Cofeld who helmed the premiere in Los Angeles five years ago and brought to life by a quartet of committed actors, the events don’t really trace a narrative and no one truly changes anyone’s mind, which is accurate but fails to put on a climax-like button on the play other than a sense that they will go forward with their individual efforts.

Yet, Powers, Cofeld and the cast’s investigation is unfailingly compelling and illuminating in illustrating the co-existence of these proactive responses to virulent racism and endemic epidemic white supremacy.

As serious as the subject matter is, humor pervades much of the 85-minute play because the event is still a gathering of good friends who jettison the personas of posturing and pontificating that they have crafted for the outside world. It is suffused with the repartee of people who are fond of each other, who know each other’s strengths and flaws – and enjoy teasing each other.

Clay says, “You would not catch me playing football. Ever.” Brown asks why not. Clay answers, “Well, you can get hurt playing football, Jim.”

Cooke teases Brown that if he agrees with Malcolm’s take-no-guff approach, “why don’t you become a Muslim too?” To which Brown shoots back, tongue firmly in cheek, “Shit, have you tasted my grandmother’s pork chops?”

The reason this private party even occurred was because after Clay won the title at the Miami Beach Convention Center, the city’s facilities both for housing and celebrations were off-limits to African-Americans (This was true even for black entertainers headlining the Miami Beach clubs). So the friends met at the Hampton Hotel in Brownsville near present day Liberty City. (This production is at Lincoln Road’s Colony Theatre, which itself was segregated at the time).

The meeting came at a crucial point in each man’s life. Clay, who had been trying to get the Nation of Islam to accept him, planned to use his new status to win over the movement’s reluctant leadership and make his conversion inescapably public by adopting the name Muhammad Ali. His political and spiritual mentor, Malcolm X was increasingly at odds with the Nation of Islam and was a few weeks from publically breaking ranks. Brown was a record-setting running back for the Cleveland Browns, but he had just finished a small role in a western and was seeing that becoming an action-oriented non-Sidney Poitier-type actor provided him a post-football future. Cooke, who was deep into producing and managing his own work, had a string of pop hits, but was beginning to explore songs that reflected racial strife. Cooke would be shot to death that December and Malcolm X assassinated nearly a year after this meeting.

The play starts with Cooke (Leon Thomas III who has played the part before) entering the room alone – after being searched by two Nation bodyguards – and quietly composing on a guitar.

In bursts, Clay (Kieron Anthony), a living tornado of boasting energy, careening around the room and bouncing atop the bed. Soon we will see that publicity pose dialed back and even see him make fun of it: He will tell his friends, “Look, Alexander the Great conquered the whole world when he was only 30. And I conquered the world of boxing at 22, without sustaining so much as a scratch. Y’all might as well start calling me Cassius the Great right now!” To which Cooke and Brown mockingly bow to him.

Brown (Esau Pritchett) is older and more experienced, but quietly appreciative, and teases his friend, including serving as a faux sparring partner in a nimble shadow boxing sequence.

Finally, Malcolm (Jason Delane) arrives. With these people, he is more friendly, playful, open and less stiff than the face he projects outside this room. But he is clearly under stress that is tying up his insides.

In the next hour-plus, their ideas and attitudes swirl and collide. Malcolm, of course, believes in aggressive outspoken activism, even endorsing violence if need be. He has recently called the assassination of John F. Kennedy as the “chickens coming home to roost.”

Clay is influenced by Malcolm’s beliefs, but is more interested in using his fame and ability to establish the unquestionable preeminence of a black man in some aspect of the multi-racial society. He never quite articulates it that way, but the under-thrust is clear.

Brown is more pragmatic and skeptical of the efficacy of movements. Similarly to Clay, he has earned respect and admiration across racial divides by his prowess, but he nurses a deep resentment that Clay’s approach has not worked for him. He is looking ahead to films for an assured personal future.

Cooke has realized that now he has established a solid footing with songs like “You Send Me” that he can move into some subtle message songs like the one he tries out on his friends “A Change Is Gonna Come.” (Thomas’ performance of the number is a highlight of the evening). But what Cooke believes is that the way to overcome racism is through economic independence. He owns his own record label, publishes his music and is building an empire of music of colleagues like Bobby Womack whose recent song was profitably re-recorded by a new white group, The Rolling Stones –with considerable royalties pouring in. He says, “Everybody out here talks about how they want a piece of the pie. Well, I don’t. I want the damn recipe.”

Powers’ script explores these ideas in depth with just a whiff of something polemic. Especially at issue is how and whether the three younger men have lost their commitment to the cause amid their celebrity and should they use that celebrity. Malcolm says to Brown, “If anything, brothers like him, you and Cassius. You all are our greatest weapons.” Brown retorts angrily, “We’re not anyone’s weapons, Malcolm. We’re men! And we’re family.”

Cofeld, a member of the New World School of the Arts’ original first graduating class, deftly moves the play fluidly, keeps the tone light enough so you don’t feel lectured to, ensures the actors create real people rather than icons and stages everything subtly so the audience is always nudged to look where he and Powers want you to be looking.

To be fair, none of the actors bear more than the vaguest resemblance to their real counterparts, which us not too much of a problem except for the unforgettable visage of Muhammad Ali.

But all of the actors are so deeply committed to inhabit their roles and they have an engaging inherent charisma that the audience never feels they are watching performances.

This is crucial for Anthony who, may not look or even sound like Ali, but who has captured that unforgettable image of an adrenaline-driven force of youthful nature. For those whom might have been put off by the public persona’s uninhibited confidence and borderline arrogance, Anthony makes it clear that Clay – while proud and confident – was putting on a show for the television cameras.

But Delane is just a dynamic in a much quieter way. His passion ignites as he explains why Malcolm is wooing Clay. “There is no more room for anyone, not you, not me, no one, to be standing on the fence anymore. People are quite literally dying out there on the streets. And a line has got to be drawn in the sand. A line that says, either you stand on this side with us, or you stand on that side against us. And I believe in that brother’s potential too much to let him stay over on the other side.”

Pritchett has the least showy role, but he imbues Brown with a hard-won dignity and clarity of vision of an unjust unforgiving world. He also project’s Brown’s barely banked anger at being accepted by whites solely for his prowess rather than his rights as a human being. Pritchett lets Brown explode with the lines, “Some white folks cannot wait to pat themselves on the back for not being cruel to us. Like we should be singing hosannas because they had the kindness in their hearts to almost treat us like real human beings. Do you expect a dog to give you a medal just because you didn’t kick it that day?”

Thomas is just as convincing as a prescient young man who knows exactly the course he wants to take. And, again, he sings beautifully.

Local actors Jovon Jacobs (various Shorts programs) and Roderick Randle (Motherland and Ronia, the Robber’s Daughter) play the two bodyguards who are likely spying on Malcolm for the Nation.

The work of the lighting, sound and set designers is as solid as it gets. The set is particularly impressive — a period-perfect hotel room backed by the exterior of a two-story motel that looks disturbingly like the one where Martin Luther King was shot.

Of course, what is inescapable in this evening, thanks to Powers, Cofeld and the actors, is that however far this society has evolved in the intervening half-century, much has remained unchanged. Some manifestations of racism have only morphed into barely different paradigms.

One Night In Miami from Miami New Drama plays through Nov. 18 at the Colony Theatre, 1040 Lincoln Road, Miami Beach. Shows 8 p.m. Thursday-Saturday, 3 p.m. Sundays. Running time 85 minutes with no intermission. Tickets $38-$65. Visit miaminewdrama.org or https://www.colonymb.org.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design