(This is an expanded and slightly different version of the story that ran last week at American Theatre magazine. See the original article at https://tinyurl.com/5ytv4wxp)

By Bill Hirschman

What audiences have seen, are seeing and will see across American regional stages has been quietly crippled and artistically hidden post-pandemic in a strangulation that only insiders have known about.

It has undermined everything from the expanse of a set to actors’ blocking to the director’s vision – and especially to what titles are being chosen for the 2023-2024 season.

Simply, it’s extremely difficult to find enough competent craftspeople, sometimes even untrained laborers to hammer sets, paint flats or sew costumes for professional regional theaters – least of all staffers experienced in the rarefied sub-specialty of theater work. Similarly, it’s become much harder to find designers who are not overloaded.

“It’s every theater that I talk to throughout the country and through (the Theatre Communications Group),” said William Hayes, producing artistic director of the nationally-respected Palm Beach Dramaworks. “There are zoom sessions with management throughout the country, and theaters are terrified…. Because you can have all the money in the world, but when nobody’s left in the industry, that is not going to help you.”

The labor famine has become a protracted crisis, said Patrick Fitzwater, artistic director and co-founder of the acclaimed Slow Burn Theater Company in Fort Lauderdale.

His company noted for its extensive sets and costumes for musicals opened its own scene shop about a year ago, culminating its dream of completely producing its own scenery of its own designs.

But now, “I can’t staff it. It’s just sitting there. And it has a brand new CNC (computer-controlled cutting) machine in there that nobody can operate. It’s a two-year lease, and we’re not using it at all. It’s an over glorified storage space. It still came down to the fact you could have all tools, but you had to have the labor and skills.”

The problems he cites intensified and turned in on themselves reflecting the situation across the nation shared by 17 interviewed professionals.

Slow Burn’s Little Shop of Horrors

The entire set of Slow Burn’s Little Shop of Horrors last October “was supposed to turn around, but there were no scenic people to really oversee that. So you ended up with a 5,000-pound house on stage that couldn’t function.”

Its two-level set for Footloose built by workers they could find seemed so unsteady that its second tier was scrapped during 11th-hour rehearsals and the show reblocked the night before opening last December.

Reluctantly, Slow Burn sent its design for the upcoming Newsies to a New York firm to build at a huge increase in cost, let alone the uncertainty of getting it shipped on time.

The burden sounds so prosaic, it’s hard for civilians to appreciate its impact. But not for those on the other side of the footlights. From Seattle to Chicago, Milwaukee to Philadelphia, Miami-Dade County to Palm Beach County, artistic directors, designers and artisans in professional regional theaters interviewed seemingly spoke from the same script.

At Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theatre Company, Director of Production Tom Pearl detailed the challenge: “Jobs that used to take us three phone calls or emails to fill, now we will find we offer a position to 12 people before we find one person to take it.”

Alongside the staffing problem, the creation of sets and costumes is maimed by two other issues: a sharp increase in the cost of materials while income from subscriptions returns are still struggling, plus the unreliability of the supply chain.

And it all affects what you see on stage. “There are clear marching orders early on from theaters for simpler, less complex and staff-demanding designs. There’s a lot more lean into abstraction and theatrical convention as opposed to kitchen realism,” said Jordon Armstrong, managing director for MNM Theatre Company in Palm Beach County who also runs the company’s scene shop.

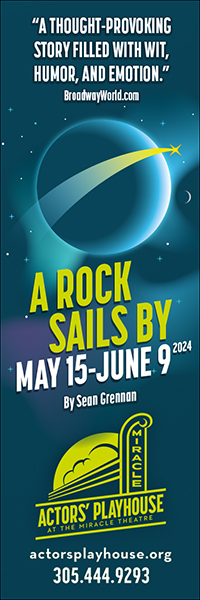

At the 35-year-old tentpole Actors’ Playhouse in Coral Gables, “We can’t do what we used to do. Those discussions happen every day. The sets have to be more minimalistic. The sets have to be more suggestive. The sets need to be less glorious,” said David Arisco, artistic director.

“INTO THE WOODS”

In the winter of 2020, many regional theaters employed a technical director, and a handful of full-time crew for sets and costumes. But they had a crucial reliance on a variable number of experienced gig workers without benefits who might put in four to six weeks, then be left to their own devices for a month or two, then back for another three to six weeks.

When COVID slammed the production door that spring, not only were the gig workers unnecessary and let go, but so were most of the tech workers including supervisors and managers.

Jodi Dellaventura

The unexpected slamming on the brakes was traumatic for veterans like Jodie Dellaventura, best known as the go-to prop mistress in South Florida, but who also could be found hammering flats, painting canvas and designing scenery.

“Even though you have a solid job, it was taken away and you have no control. There was nothing like it. I didn’t work for two years,” she said.

Some companies labored to keep retain staff. A rarity, Milwaukee Rep, laid off 10 to 20 percent of its staff as opposed to most theaters that instantly fired 60 to 90 percent, and the Rep sought grants from philanthropists to keep their pay reliable.

“We repurposed their skill set. They were building PPE for our hospitals,” said Executive Director Chad Bauman said. “We knew that if we didn’t keep them employed, they would not only leave our theater, they would leave the field. And then when we tried to reopen, we wouldn’t be able to reopen.”

But elsewhere, the exodus was devastating: Carpenters, painters, welders, electricians, designers, seamstresses, technical directors.

“They weren’t going to sit around and be like, well, theater will come back one day. They started to go and find that the skills that they were using in theater could easily be applied to other areas,” said Matt Stabile, producing artistic director of Theater Lab, the resident professional company at Florida Atlantic University, which specializes in new work.

Those developed skills were highly marketable in a dozen areas: television, theme parks, corporate events, events, cruise ships, Vegas shows and multi-million-dollar weddings. Carpenters just could build cabinets. For the most skilled, companies serving those other customers snatched up the artisans with higher pay and benefits.

“People who are either welders or carpenters, they’re working in shops now, making whatever 30, 50, whatever, dollars an hour working and building stuff,” Dellaventura said.

Crafts people “realized, ‘Why am I working six jobs to work in the theater and make this much money when I could just do this (one full-time job)? And the hell with my passion,’ right?” said Arisco. “It’s not like they don’t have a passion for wanting to work in the arts. They do. They love what they do. But they also have bigger issues with paying their bills or juggling many jobs instead of having one that finally came through with benefits or finally came through with a decent pay rate.”

Matt Stabile

Stabile went further: “Frankly, it’s not shocking that some of those people would choose to not return to an industry that was kind of … ‘The show must go on and the play is the thing,’ and all these, like, little phrases we like to make ourselves feel better. But ultimately, it’s people putting that product together, and it can become exhausting to be… ‘I’m going to put in 60 hours just to get the show up and running.’ ”

Maura Gergerich had built a career in Florida regional theaters as a master carpenter with added skills in drafting, rigging, painting, welding and sewing, culminating in a full-time job at Actors’ Playhouse in Coral Gables and “side hustles” elsewhere.

When work shut down there trying to open Camelot, “I think most people thought that it would be a couple of weeks because nothing like this had ever happened in our lifetime. So it wasn’t even fathomable to think that our entire industry would be shut down for a year and a half,” she said.

The theater continued to pay people through June and tried virtual productions that used her skills. But eventually, most work and the pay evaporated.

Initially, she welcomed the opportunity to take deep breaths, start a garden and collect puzzles and unemployment. “Ironically, it was kind of nice to not have to worry about grinding and struggling and finding gig after gig.”

But eventually, “it was just always sort of a kind of ebb and flow feeling of like, ‘I miss doing something that feels productive. I miss contributing to something’ because as nice as my side projects were or my home projects, it didn’t feel like you were producing something for a purpose.”

Many went back to school to finish degrees or add a new one. Many retrained in other professions. Some learned advanced computer skills.

As the months turned into years, Bauman said, “even in the performing arts, opera opened before we did…. We were the last to reopen. The longer we remain closed, the more instability began to creep in in terms of employment.”

But as the COVID figures dipped, producers and artistic directors began playing with limited productions and planned a return to a full season with that skilled staff.

The problem was they were gone.

“IS ANYBODY THERE?”

For many, it wasn’t recontacting them in other jobs they had found locally. “They had moved to the Carolinas. This painter moved back to Milwaukee. Everybody relocated,” said Kimberly Wick, associate producer at The Wick Theatre and Costume Museum in Boca Raton.

The irony is that even in Chicago where some smaller companies folded or remain in limbo – and the reduced opportunities therefore are more precious to potential workers — the number of people willing to work in theater has shrunk, said Steppenwolf’s Pearl.

When veteran national scenic designer Sean McClelland designed the Wick Theatre’s Cinderella, he said the dearth of scenic painters led the company to reach out to 30 scenic painters in New York City—with no result.

Finally, Kimberly Wick said, “We had a painter drive over at nine o’clock at night from the west coast of Florida. She stayed in a hotel. She painted for three days. Then she went back. Then she came the following weekend, painted for three days, and then she went back, and I finished it. I painted half of the set for Cinderella… But after (doing the same for) Damn Yankees and that insanity, I took my paint clothes and threw them in a ball and threw them out. I said, ‘I am not painting another set. I am 60 years old, and I can’t do it anymore.’ ”

Wick’s Cinderella

Similarly, Slow Burn’s Fitzwater and Managing Director Matthew Korinko found themselves with paint brushes in hand.

“It’s like all the theaters are pulling out the same three (scenic artists) that are still available,” said McClelland, owner of Symbiont Scenic in Santa Fe.

As a result, simply the number of people actually designing and building sets and costumes has dwindled. Actors’ Playhouse once had six to seven regularly employed staff in the scenic shop, now three or four; once, there were four in the costume shop, now one.

Sean McClelland

With supervisory technical directors filling in on everything from design to engineering to hammering nails, their disappearance is no surprise to McClelland: “The TDs are so burned out…. Who wants to work for $40,000 a year, be in charge of building all the shows, the building’s maintenance, everything on top of it?… Now theaters can’t even fill the top position, which is ridiculous.”

Many scenic and costume designers also left the “legit” theater as well, leaving the remainder facing overwhelming workloads.

McClelland is still doing some of the corporate work that got him through the pandemic, but this past season he had six assignments and he has others on the table. He’s glad for the work, but the amount reminds him of designing colleagues who have left the business because they were burned out.

Until recently, Rick Pena, a founding member of Slow Burn Theater and its long-time costume chief, had spent the pandemic designing costumes at American Heritage School, a well-heeled private school with an unusually large theater program in Plantation.

“The only reason I’m back at Slow Burn (now) is because they offered me a salary with benefits, which is unheard of. I can probably count, not even on my hand, how many costume designers have that in South Florida.”

STRUGGLING THROUGH

The short-term stopgaps have been simple but deeply problematic: renting sets and costumes, or hiring an outside company to do the work at an even higher cost, or hire inexperienced hands.

The lack of experience even among the most eager newbies pose an issue, especially in the specialized art of theatrical scenery and costumes.

“There’s a real difference between someone who’s been doing it 5, 10, 15 years and someone who’s been doing it 5, 10, 15 months,” said Dramaworks’ Hayes. “We have, in recent days, gotten applicants, but … the resumes are so weak that I wouldn’t even give them an interview.”

For instance, “There’s three stages to a paint job,” McClelland said. “That’s how you get the depth, that’s how you get the illumination. There’s an art to it, and …. now, what you have on stage looks like something that you got a couple of volunteers … to come in and paint it.”

Jordon Armstrong

MNM Theatre Company’s scene shop has stayed operational by designing and/or building/and or installing about 20 productions total in the past season with two full time carpenters – often for other companies in the region, Armstrong said.

“The one downside of theater carpentry is you can’t just get a contractor come in and build stuff. I mean, they could do it, but it’s going to be overly expensive and overly heavy because they’re used to building houses and walls and support structures as opposed to facades. We make a bunch of boxes and tell the audience they’re not boxes. It’s all smoke and mirrors…. There’s architecture in it, but it’s architecture that is built out of Popsicle sticks and sheer will.”

And with ever tighter timelines, there’s not a lot of time for the old hands to train the most willing newcomers on the job.

“I used to always be the younger guy. Now I’m the older guy,” McClelland said. “And the work ethic is just different. They don’t want to work more than 40 hours a week, and they don’t want to ask questions.”

The fallback cited over and over is hiring outside companies. But the cost of farming it out is considerable, said Morgan Green, lead artistic director for the Wilma Theater in Philadelphia.

“It’s one of the most expensive things. Easily five times more expensive than any other component of the production,” Green said.

A few years ago, an outside company might charge $8,000 to produce a set; now it can be $35,000 to $45,000, McClelland said.

Under it all, the theaters are striving to keep their loyal audiences from noticing any significant change in quality or even scope. Some companies felt their audience’s past expectations for impressive sets and costuming forced them to dig even deeper when they initially reopened – a kind of Sondheim declaration that “We’re still here.”

Milwaukee Rep, for instance, re-opened with a 33-actor version of Titanic, helped by the fact that they had kept much of their staff employed. “Our thought process was we wanted to give somebody a reason to get off their couch and away from Netflix,” Bauman said.

“MONEY, MONEY, MONEY”

Exacerbating the issue of what you see on stage is what it costs in materials these days – when you can get them.

“We are seeing sometimes a 30-to-50 percent increase in the price of materials,” said John Langs, artistic director at ACT in Seattle.

Steel, hammers, screwdrivers, the very casters to roll on scenery doubled in cost. While the hikes have subsided a bit, bills for the crucial element of lumber tripled earlier in the comeback, Stabile said.

Even price tags have doubled for items the public doesn’t even think about like 3M adhesive spray and spray paint, Wick said.

Decisions had to be made on spreadsheets. “It’s always the fine line of is it going to cost more with a man-hour labor to fix it up or is it worth getting new?” Armstrong said.

And truly aggravating is that even when you have the workers, you may not have the materials in hand for them to work on due to a serious unreliability in the supply chain and previously reliable sources.

“That goes to everything,” said Steppenwolf’s Pearl. “In the beginning, it was plywood, manufactured goods. The scene shop now has to keep hardware on hand. But say our costume shop needs a red slip. We used to go to two or three shops, now we have to go to seven or eight. We have had to pivot in our expectations because of Amazon and overnight delivery is not always reliable.”

Planning ahead is no assurance. ACT’s Langs said, “Even when we think we’re months ahead, we just sit there biting our nails, going, ‘Is it going to get here on time so that we have time to do the excellent work that we know how to do?’ ”

SOLUTIONS: “PUTTING IT TOGETHER”

Companies have been experimenting with and weighing a dozen solutions, some temporary, some permanent. Still, crucially, the priority that most audience members should not be able to discern any loss in artistic quality.

—One obvious change this spring has been considering the specific expanse of scenery, racks of costumes and rising costs in deciding which titles to include in the next season. Some companies like Palm Beach Dramaworks selecting their 2023-24 slate have been choosing one or two titles with elaborate sets interspersed with those only needing minimalist scenery and a reliance on lights and sound for titles that requires a variety of scenic backgrounds.

Hayes, whose company’s sets have been especially memorable down to the props, is considering reviving its acclaimed 2003 production of The Dresser with a simpler set. Plus, for its upcoming Death of a Salesman, “we just think it doesn’t have to be trying to duplicate a variation of the original Broadway one. I’m not going to say that I don’t want at least one show in a season that has an impressive set that people are used to seeing at Dramaworks, but there’s other ways to skin a cat.… I have superior lighting designers and sound designers, and you’d be surprised.”

—With those strategic decisions made earlier than ever, designs are being crafted to reintegrate pieces from one show in the season to two or three of them. At the Wilma Theater, designer Matt Saunders “chose some standard sizes for the platforms and for the walls so that we didn’t have to have them custom built” for each show, Green said. “We could use existing flats and platforms and just paint them a different color.”

It means some are designing more easily-built sets and costumes that can cross the season. ACT in Seattle and “other theaters are treating designs like we would if we were running repertory theaters… employing a single designer to do a repertory plot for the season in order to save on the labor that it takes to do a full strike and rehang and focus. We’re looking at …saying, here’s the whole pie of the year, and here are the seven stories that we’re going to tell within this that have to be told with these resources,” Langs said.

—-Once, many theaters indiscriminately scrapped nearly everything to the garbage pickup alley after strike. No more.

The set for MNM Theatre’s The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee “was entirely stock pieces that we repurposed, repainted, cleaned up. It’s cheaper to clean up the dings and the staple holes on old pieces than it is to buy new materials,” Armstrong said.

At Theater Lab, “There’s been times where it’s been like, yeah, all we have is this warped, non-good four by eight plywood, and we’re like, we’ll have to cut that up and make it work,” Stabile said.

But saving scenery, props, costumes and the like pose a second problem: Most companies have limited or even no storage space, and renting warehouse space is an added expense for the budget.

—-Technical advances have cut down on the amount (and thereby the cost) of materials and manpower. Many theaters now rely heavily on projections – ever more artistically inventive, animated and artfully merged into roll-on mini-sets and furniture. With its larger budget, the Maltz Jupiter Theatre in Palm Beach County installed a full stage LED screen this past season.

—- Some stagger the required hours over shorter work days but a longer number of days. “We made the build weeks longer, which costs more money. So that way we could bring people in who weren’t working their day jobs to come in from six to ten at night to build rather than an eight-hour day,” said Slow Burn’s Fitzwater.

—-The competition for local workers is fierce, Milwaukee’s Bauman said. Some theaters are desperate enough to import workers from outside their region, but that requires housing and other amenities just like those for an actor or director.

—-Some have decided to have a smaller temporary crew but hire full-timers with decent pay and benefits to gain the reliability factor and the speed that comes from their experience.

—-Cooperation among collegial theaters in a region has been common. It could be as informal as calling around to borrow workers or just to get leads on potential crew.

—-If the company is associated with a college drama department, students are being hired for pay or given an internship during the summer to begin work for the coming season. But few of them have the experience level, and what little staff remain must train them in the basics – a time-diverting delay and not cost-effective.

—-When preferred set and costume designers are overwhelmed, some theaters have borrowed designs and rented their scenery. Even with its own sophisticated scene shop, the Maltz Jupiter Theatre rented Geva Theatre in Rochester’s main drape for A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum plus its technical drawings to adapt for the Maltz’s specific stage. For its Oliver, it outsourced the technical drawings of their design from a technical director from The Muny in St. Louis. Still, Producing Artistic Director Andrew Kato mourned the loss of the cherished opportunity to have a revolve echoing Broadway’s original.

William Hayes

—-Hayes, whose Dramaworks also has its own scene and costume shops, suggests a provocative blue-sky proposal that takes cooperation to a more formal business level: Three or four similarly-sized theaters sharing a central production center. They jointly could pay competitive salaries for experienced hands as well as provide plenty of full-time work, especially if the theaters began their design a full year in advance. Although government-supported and now closed, a similar paradigm combined with production spaces called the Arts Incubator operated for years in an old school building in Arlington, Virginia.

—-One possible option in the future for the thousands of dollars spent on designs – one that few interviewees welcome – are architectural artificial intelligence programs like Midjourney that have been used “on paper” to create the initial visual set design images.

“There’s already college kids writing pieces on it and how they think it’s going to replace all set designers in ten years,” McClelland said. “Some people have gotten pretty good at it. They’ll be like, ‘I want to do Wicked with an Andy Warhol sensibility.’ And it just instantly pops up images of what that set would look like. There’s already a lawsuit starting.”

CHANGING MORE THAN THE SCENERY

But a key change has to do with pay and working conditions: the traditional 10 hours out of a 12-hour stretch has been cut back, work weeks are cut back. The goal is to eliminate the burnout that has claimed more than a few veteran hands.

“The theater used to run on people’s goodwill, and people would work endless hours and late into the night and make it happen. And it was out of passion. And that is no longer acceptable. That is not a healthy work environment,” the Wilma’s Green said.

“We’re really, at the moment, dedicated to this cultural shift where it’s a good place to work. You are compensated fairly for your labor, and you are treated well, and you feel safe when you come to work, et cetera. And that just means that it’s more expensive…. And that means that there’s less money for other things, so we’re putting more resources toward the people rather than the work, but then the work suffers. So we have to find a balance,” Green added.

At Theater Lab, Stabile said, “I hope that the outcome is that we’re starting to value those people more. We’ve been doing a lot of work at our theater about what systems can we put in place to make sure that we’re providing ample time to get projects finished and that nobody has to pull an all-nighter.”

Of course, a key element is the fiscal challenge of making the work financially attractive – when budgets have been sliced by the economy and the slow regrowth of subscriptions.

Some theaters are still paying $12 to $15 an hour to the lowest tier of worker as they did pre-pandemic, although most have added a few dollars an hour to the rate. Others like the Maltz Jupiter Theatre are trying to pay competitive wages, especially to cope with increased costs of living in Florida. But few if any can compete with the professional event building companies that can pay $20, $30, even $40 an hour plus benefits if the staffer is hired full time.

“OPEN A NEW WINDOW”

Looking ahead, most interviewees exuded that unique theatrical meld of hope and practicality but with few concrete predictions. “Theaters are always a survivor,” McClelland said.

The good news is that while prices are much higher than pre-pandemic, some bills for items like lumber and steel have begun to decrease a bit.

But as far as people to build and paint sets, to sew costumes, the theaters have marked a noticeable drop in people coming out of schools willing to work onstage, backstage or in the shops as professionals.

McClelland’s hope: “…that the next batch of college kids coming through are going to realize that there is a higher demand for this field that pays (well) compared to five years ago when you came out of college with a degree in tech or design and you found a low-level internship somewhere. I hope they realize there is quite a demand and the possibility of an actual career.”

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design