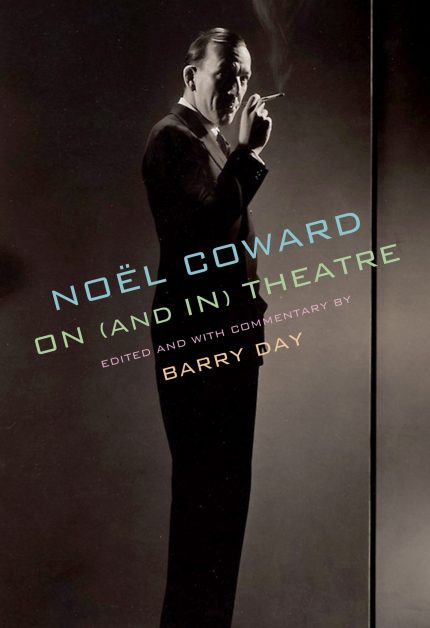

Noel Coward On (And In) Theatre, edited and with commentary by Barry Day, Knopf. 183 photos. 496 pages. $40

Noel Coward On (And In) Theatre, edited and with commentary by Barry Day, Knopf. 183 photos. 496 pages. $40

By Bill Hirschman

Noël Coward meant to write a full tome on “Theatre” but time, health and a score of other projects apparently got in the way.oward

But Barry Day, a stage producer, biographer of literary figures, Sherlock Holmes novelist and prolific Coward devotee, realized that Coward had in essence done it indirectly.

Thus, the germ for Noel Coward On (And In) The Theatre.

Via letters, magazines articles, poems, song lyrics, diary entries, speeches inside his plays and a half-dozen other venues, Coward had written extensively, almost exhaustively during his lifetime about the art and craft of playwriting, acting, songwriting, directing, producing and the realities of dealing with other denizens in the mercurial world of theater.

As he has done with other writers, Day has organized literally hundreds and hundreds of these quotes, articles and published insights into Noel Coward On (and on) Theatre – a 450-plus-page journey in which Day serves as a context-setting tour guide through Coward’s observations.

Day writes, “He was a true Renaissance Man – who just happened to live in the twentieth century.”

Day’s own insights are solid most of the time, but his encyclopedic knowledge of Coward’s life and work is invaluable in organizing this project, embellished with scores upon scores of photos, playbill covers, handwritten song lyrics and drawings.

For those under a certain age, Coward’s name, reputation and rarely-revived work speak of another time – the first two-thirds of the 20th Century when manners, style, self-deprecation and a cosmopolitan elegance ruled.

But today’s shallow perception of Coward’s persona primarily as a witty sophisticate — a fiction he constructed out of a modest background in class-conscious England – badly underestimates the complex and talented artist who actually was one of a handful of theatrical figures who helped transformed British theater — and by extension theater on both sides of the pond.

Genuinely fascinating is to realize – as Coward himself did – that Coward was once the cutting edge of his time. He began his career in the classic drawing room theater of the early 20th century, evolved during two World Wars, but ended up as the epitome of a style quickly being left behind. While appreciative of great theater no matter the genre or approach, we see him struggling as the Angry Young Man movement takes over, erasing much of his popularity.

Particularly striking is how Coward’s observations, first written down in his youth and then revaluated in his senior years, chart that change in British theater: staid drawing room offerings at one end and message plays with social import at the other end. In fact, he cherishes finely wrought comedy for its entertainment value as well as heartfelt plays, but in his estimation entertainment ought to be the priority.

His studied how-to’s are invaluable: He strongly believes that comedy is far harder to play than drama because comedy requires even more techniques to be consistently successful eight shows a week than drama. For instance, when a line of dialogue has two bits of humor in it – the initial one sentence that is humorous shouldn’t be hammered at in delivery, otherwise it will undercut the more pungent humor of the punch line later.

Barry Day

Day’s vision underscores Coward’s workmanlike devotion to the craft by allowing his hero to hold forth on inside baseball details of everything from how line readings in comedy are far more challenging than those in the most dramas, to how witty dialogue is entertaining but careful construction of a play is far more crucial in its worth and success. He advised actors to learn their lines before the first day of rehearsal and then develop the character. He was no fan of Stanislavski.

He also was supremely practical and realistic, willing to play Las Vegas or even do a magazine ad for a beer.

It contains little reference to his sexuality and virtually none to his work in films.

Throughout, Coward holds forth, evaluating nearly every major British and American theater star of the period, many of whom were friends but whose weaknesses and foibles he catalogues with as much clinical honesty as his awe and respect: Lunt and Fontanne, Gielgud, Olivier, Bea Lillie and a score of others – drunks, divas and geniuses.

Day is an old hand at this paradigm. He did similar work in volumes focusing on P.G. Wodehouse, Raymond Chandler, Oscar Wilde and Dorothy Parker.

As a guide, Day has no problem allowing Coward to repeat the same observation re-quoted in a different medium. He even pulls quotes in one topic and then later publishes the entire source article.

This volume is almost overwhelming in its detail, almost to the point of wanting to fast forward to “the good bits,” but Coward is such fascinating company that it would be boorish to complain.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design