(This is a column from the veteran theater critic and classical music enthusiast Brad Hathaway who wrote several Theater Shelf columns for us in the past, especially about theater-related music and recordings. Here he dissects how musical theater icon Frank Wildhorn of Jekyll & Hyde fame has moved in an adjacent field.)

By Brad Hathaway

Theater Shelf is stepping very briefly out of the shadows of retirement to help spread the word of some new and quite beautiful music that has received too little attention from my reviewing colleagues. My theater critic brethren may be passing over this music because it is not “theater music,” while classical music critics may be passing it over because it is not the work of an acknowledged practitioner of the symphonic arts. Both are missing the boat!

Frank Wildhorn, who went from successful pop composer to successful theater composer, has entered a new field — symphonic works for the classical concert hall. Soaring melodies have been a hallmark of his theater works, so it is not surprising that his symphonic work sings. But he stretches his melodies to new lengths while using the widest possible dynamic range and rhythmic complexity to maintain the listener’s interest over longer spans than theater works utilize. The result is both beautiful and exciting on a grand scale.

Wildhorn’s productivity is somewhat staggering. Before his first effort in musical theater he had already written hit songs for the likes of Whitney Houston, Natalie Cole and Kenny Rodgers. Starting in 1990 he composed show after show, having three musicals (Jekyll & Hyde, The Scarlet Pimpernel, The Civil War) running on Broadway simultaneously. Three more (so far) have opened on Broadway (Dracula, Wonderland, Bonnie & Clyde) while his shows for theaters in Europe and Asia have multiplied at a great rate. He now has composed scores for 46 shows that have had countless productions around the world.

His first foray into this new genre for him received its world premiere by the Wiener Symphoniker (or Vienna Symphony Orchestra) in 2022. It was The Danube Symphony. It proved to be a tremendously melodious, highly charged and thoroughly satisfying nine-movement work for a huge orchestra. It was recorded by that orchestra and released by the Austrian label HitSquad Records that had released many recordings of Wildhorn’s musical theater scores.

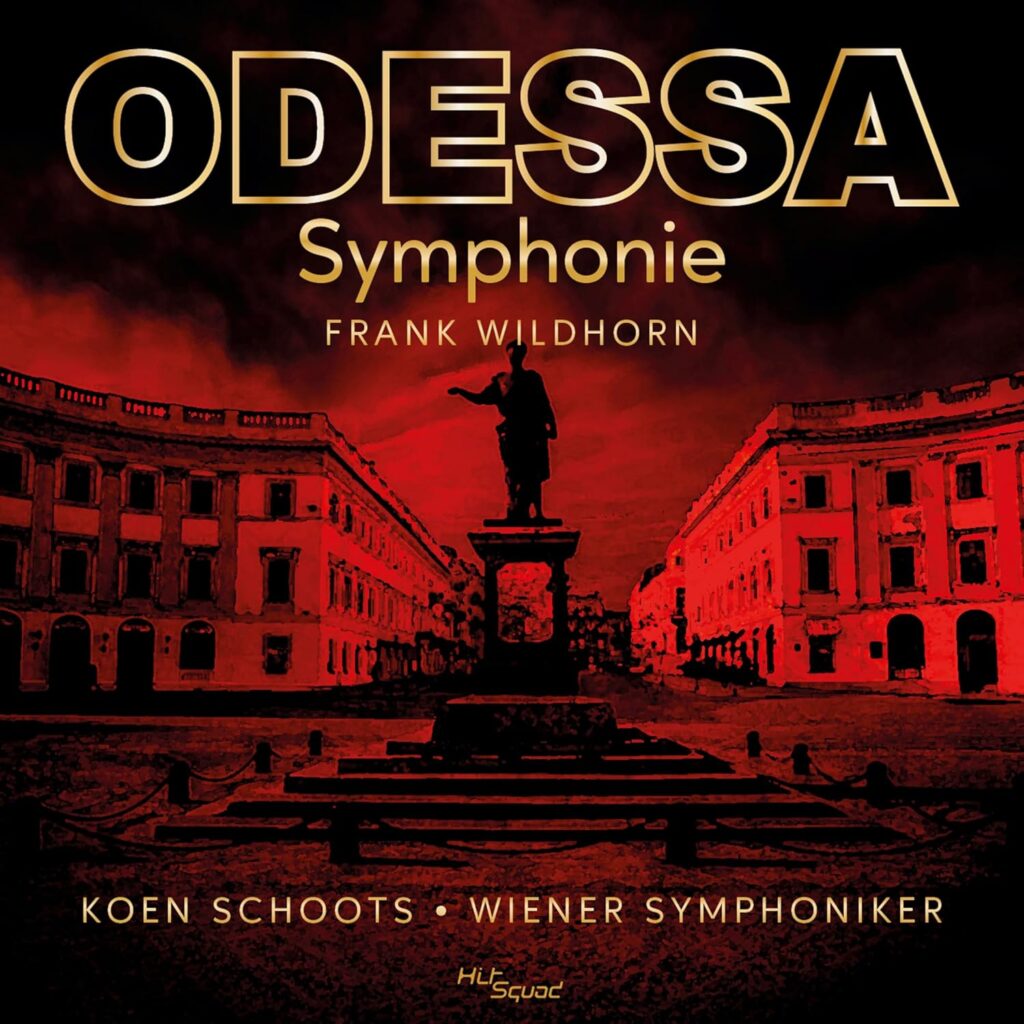

A second symphony titled Odessa Symphony just received its world premiere live performance in the city of Ulm in southern Germany, after having a recording released on that same label. Both the live performance and the recording were by the same Wiener Symphoniker. Their sound was full, clear and exciting in both the live performance and the recording.

Here, Wildhorn is working without a lyricist or librettist of musical theater collaboration, but one gets the feeling he was not without collaborators. Kim Scharnberg, who orchestrated a good number of his shows over the decades, was both an orchestrator and — in Wildhorn’s own word — his “guru” guiding him through his introduction to the symphonic genre and contributing colors and depth to the transition from structural sketch to full charts for eighty-some players. And Walter Feucht, who first suggested to Wildhorn that he compose a symphony, may have assisted in something akin to the contribution of librettist as the stories behind the movements evolved. For example, the fifth movement of the Odessa is Wildhorn’s effort to portray the experience of Feucht’s father who, at the end of World War II, walked from the Odessa Oblast on the Black Sea in to Ulm on the Danube River in Germany using the stars to navigate.

Still, just as with a traditional musical theater score, it is the composer who creates the work and, here, the work impresses in its symphonic impact.

The variety of symphonic effects is impressive from the start. There are lovely instrumental solos for nearly all major instruments of the orchestra (including a remarkable gypsy-tinged theme for violin opening the Odessa,) bold melodic sweeps for strings, delightful dance episodes and strident militaristic marches for the full compliment. The fourth movement of the Danube could be the rhapsodic movement of a piano concerto. The five and a half-minute build from “Call to Arms” to “Battle Royal” in the Odessada demonstrates significant orchestral dexterity. In the final analysis, this is multi-faceted music that can be appreciated in these first class recordings.

But experiencing the Wiener Symphoniker’s performance live was even better. In Ulm I was thrilled as the first movement went from hush to blast and the thrill just kept getting better. The Wiener Symphoniker with its 83 players on the stage could sound intimate one moment and then hit with an attack that seemed the symphonic equivalent of a Basie Band Blast the next.

To my fellow theater critics I say you owe it to your readers to check out this new material by a composer you have — or should have — been following for a third of a century. Tell your readers about it.

To my classical music journalist friends I have a message: If you wonder if a “mere” theater or pop composer can actually impress in a symphonic setting, get one of these discs or go to a streaming service and spend the seven and a half minutes it takes to listen to just the first movement of either symphony. I believe you will be convinced that this is music of worth. I’m sure you will want to listen to the rest of it and then spread the word to those who follow your reviewing. They will be the better for it.

– – –

Frank Wildhorn’s Donau Symphonie

Wiener Symphoniker

Running time 58:47 over 9 tracks

HitSquad Catalog 668442

Frank Wildhorn’s Odessa Symphonie

Wiener Symphoniker

Running Time 43:59 over 7 tracks

HitSquad Catalog 668485

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design