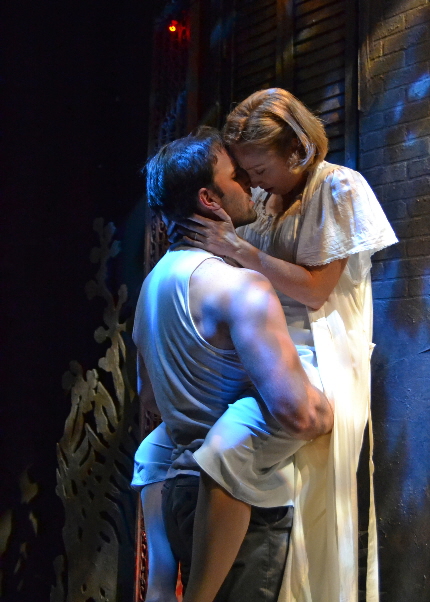

Danny Gavigan as Stanley and Annie Grier as Stella in Palm Beach Dramaworks’ A Streetcar Named Desire / Photo by Samantha Mighdoll

By Bill Hirschman

When tackling A Streetcar Named Desire, it’s impossible for theater artists to ignore the proverbial elephant in the room: not the legendary but ephemeral 1947 theater premiere, but the 1951 film that made a movie icon of Marlon Brando and provided the last great role for Vivien Leigh. But director J. Barry Lewis, actors Danny Gavigan and Kathy McCafferty don’t fear an audience with vivid memories of the film, they welcome it.

To start with, when audiences come to the Palm Beach Dramaworks’ production opening Oct. 11, they will come with stoked anticipation, the trio said in a spirited interview before a rehearsal.

“I think it’s wonderful because it’s people who are coming with a real interest and love of the story,” said McCafferty who will playing the troubled Southern belle Blanche.

Gavigan as the self-described sweaty sexy Stanley, chimed in. “So, as actors, we’ve gotten some of the work done for us and they’re coming in with an enthusiasm. I mean this is a beloved story…. Everyone has their own preconceived notions about what it’s about, but they’re all fueled by an enthusiasm that only benefits us.”

As far as competing with memories of Brando and company, Gavigan smiles and shrugs. “That’s okay. There’s nothing we can do. We have no control over it.”

But they expect their edition will surprise those who have only seen the film, starting with the fact that play is far more complex and richer than the censored film was allowed to be, said McCafferty who had never seen the play live and only viewed a 2008 videoed stage version with Laila Robbins at the Lincoln Center library.

“I think what they’ll discover is that the play on the page is very different due to so many of the censorship issue…. The depths that it is allowed to plummet to are quite different than the movie, which I love,” she said.

Indeed, when she saw that video – even after having read the script multiple times – “that last scene took my breath away. I was not prepared to see what I saw.… I was in the library trying to control my breathing so I didn’t start to cry in front of everybody.”

The Tennessee Williams period script is about Stanley and Stella Kowalski, a young couple in New Orleans whose marriage is endangered by the surprise appearance of the Stella’s troubled sister Blanche. But the play examines a dozen issues of enduring relevance, some with increased relevance in this #metoo era.

Given the climax in which the earthy Stanley attacks the fragile Blanche, “I keep thinking about this for women sitting in the audience,” McCafferty said. “We’re really fed up with sexual predatory behavior. And (the Stanley-Blanche conflagration) is not romantic violence.… But for me it’s very important that once this woman realizes what’s at stake that she does everything in her power to get out of the situation. And then it’s not some submission. It’s not romantic, it’s violent.”

She cited an even more chilling moment about women accusing their attackers: “I think when we get to the point in the story when the audience realizes that (Stella) has not believed her sister. Nobody believes her.” Lewis added, “She’s alone.”

The play brings in a half-dozen other familiar issues. “Health care, losing your family estate, poverty, mental health, stress in a marriage, ageism,” she said. Lewis chimed in, “And sexual identity.” McCafferty grew the list: “I think the light bulbs are going to go off in terms of things that they can understand relate to — loss of family… the death of parents and then preparing to become parents….Life stresses that have not changed one iota.”

Gavigan, who played Stanley in 2016 in Baltimore, said the scope of the production – the cast list has 13 characters – means “there is also a spectacle to seeing this on the stage, so much life on stage….. There’s a whole community in this small little nook of New Orleans and you see it in every scene transition.… It’s a commentary on the community and the effects that reverberate throughout their immediate community.”

It’s also darker than some people might remember. “Tennessee Williams in the play was saying everyone is accountable and complicit in this by turning a blind eye and then nothing changes because that’s what we’re doing as a society,” Gavigan said.

McCafferty agreed, “Blanche is no innocent either. She has plenty of sins to pay for on her own….We’ve seen what we’re discovering is that nobody in this play comes out unscathed. We’re all changed by it. And yet life goes on. We all have to deal with the consequences of our well-intentioned missteps, giving into our worse natures.”

But none of them are trying to reinterpret the play. It’s not necessary. “Sometimes you have to turn plays upside down so that they can be really heard by the audience. I’m discovering that this one is a play that we’ve got to get out of the way. The play is so brilliant on its own that… we all just have to take a step back and put that into the forefront,” Gavigan said.

Lewis, one of the region’s most respected directors, has frequently insisted that classic works do not have to be reinvented or deconstructed, only done justice.

“The language is what we have to go by,” Lewis said. “The key factor of this work is Williams as the poet, as the playwright, as the author, as the voice, and finding our way through that language (that shows how the characters) attempt to communicate to each other… how they succeed, how they fail.”

The challenge in his view is always “trying to be clear as to what we think the author’s intentions were originally and bring our talents to play. It’s not frozen in time. The script is frozen… but here we have the capability of breathing life into that language from our own talent.”

Sitting alongside a shoebox-size model of Anne Mundell’s design of a two-story apartment house in the French Quarter, the three speak ever more quickly, finishing each other sentences and inserting their ideas in mid-sentence as if they were already in the privacy of a rehearsal.

It’s a familiar process for McCafferty who was directed by Lewis as Regina in 2017 in Dramaworks’ The Little Foxes and earlier as the heroine in Outside Mullingar. But the Dramaworks’ theater is new to Gavigan whose stage work has been mostly in the Baltimore-Washington, D.C., corridor. Also appearing at Dramaworks for the first time are Annie Grier as Stella Kowalski, and Brad Makarowski as Mitch, Blanche’s would-be suitor. Also in the cast are South Florida regulars Gregg Weiner and Renee Elizabeth Turner.

The trio hope one quality shines through every one of the troubled characters.

“I think this play begs us as players and the audience begs us to be compassionate,” Gavigan said. “And that in and of itself is worth hours of their time and weeks and weeks of us tearing our hair out trying to remember our lines.”

A Streetcar Named Desire will run Oct. 11-Nov. 3 at Palm Beach Dramaworks, 201 Clematis St., West Palm Beach. Show times are 7:30 p.m. Wednesday, Thursday; 8 p.m. Friday and Saturday; and 2 p.m. Wednesday, Saturday, Sunday. Individual tickets are $77. Opening night tickets at $92. Specially priced previews on October 9 and 10 at 7:30 p.m. Student tickets are available for $15, and Pay Your Age tickets are available for those 18-40. Tickets for educators are half price with proper ID (other restrictions apply). Call (561) 514-4042, or visit palmbeachdramaworks.org.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design