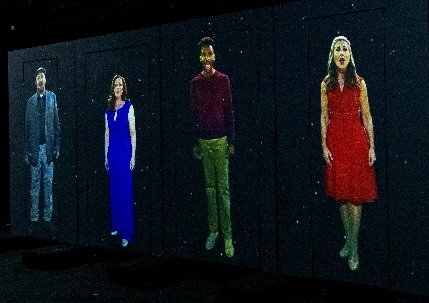

While some numbers were filmed live, this quartet of Johnbarry Green, Aaron Bower, Elijah Word and Shelley Keelor are projected onto rolling doors in MNM Theatre’s Closer Than Ever / All photos by Amy Pasquantonio

By Bill Hirschman

It’s not lost on anyone as these Florida actors sing ardent songs to each other — separated by six feet of stage — that the musical they are filming is titled Closer Than Ever.

“The title is not about this time at all,” director Jonathan Van Dyke said of the 1989 revue of Maltby & Shire relationship songs. ”But the title does says so much” unintentionally.

It’s impossible to ignore that resonance in MNM Theatre Company’s production currently being edited for online streaming release Nov. 27-Dec. 31. When a live actor reaches out to hold hands or croon to another actor, their partner might be a previously filmed image projected on a door-sized screen a few inches away.

Van Dyke, Producing Artistic Director Marcie Gorman and a tight crew of artists have refused to let the pandemic crush the Palm Beach County company, although they have had to create complex processes while maintaining strict health safety precautions.

“The concept, which involves integrating live performances with projections, is brand new. It’s what will separate this production from just being a filmed play – it’s a hybrid with three components, not just two, and as far as we know, no one has ever done anything like it before!,” Gorman was quoted in a news release.

Basically, quarantined-at-home, regularly-tested actors Aaron Bower, Shelley Keelor, Elijah Word and Johnbarry Green, rehearsed for two weeks in the company’s intimate rehearsal warehouse in Boca Raton, singing to music tracks created by musical director Eric Alsford and bassist Martha Spangler.

The entire operation teetered on a precipice: If anyone tested positive, everything would have to be, at best, postponed if not cancelled, Gorman said. Everyone was perpetually masked when not actually performing. Crew members often wore gloves.

In the third week, they were filmed simultaneously by three cameras overseen by director of photography Cliff Burgess, with parts of some numbers captured in front of green screens at one point, solos were shot one day, group numbers another with performers across the stage from each other or separated by different levels. Blank doors were rolled around the stage to create different scenes and crucially doubled as screens upon which projections of other actors were displayed. Van Dyke, who helmed MNM’s A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, sometimes donned mask and gloves himself to help move doors around on the set.

The pieces were being edited together this past week, working out glitches. Gorman noted during a phone interview that she had just seen a group number in which only one person had a body; the rest were floating heads.

It is far from even that difficult a challenge. In some cases, “live” performers are singing duets with themselves – earlier footage projected on a door screen next to them. Sometimes when a scene needs to be an intimate duet, one live actor sings to his scene partner mouthing mutely in a projection on the door screen, but the performer playing that partner is offstage singing live to their colleague as the number is being formally filmed. Sort of reverse lipsyncing.

The entire process has been an experiment of discovery for everyone because no one involved has done anything exactly like this before.

Green, who played Spamalot’s King Arthur and the father in Next to Normal, said he has done some camera work before “but nothing very extensive; I had a few moments where I got to be part of some indie films as a zombie.”

The camaraderie was palpable here as the experiment explored techniques, he said. “It felt good to have everybody silently cheering us on from the sidelines.”

Keelor, memorable as the mother in Slow Burn Theatre’s Carrie, added, “It was like a crash course into filmmaking and that’s not my background” other than having done a couple of commercials.

For performers accustomed to delivering several shows a week for a few hours, the discipline and stamina here was different, she said. “You had to do a number maybe six times because they wanted to get one more angle. (Someone says) let’s do it one more time.”

Further, “It was a lot more focus driven because if you miss a note live on stage you are not as traumatized as when you have five cameras that are picking up every nuance and facial gesture.”

Focus, indeed, was a hallmark of the process, shooting and reshooting portions of the show rather than going through the show beginning to end. Here, they concentrated on each vignette rather than the overarching arc of the show, Green said. It saved the performers from worrying about which side of the stage to reenter after exiting, not worrying about quick costume changes.

Word, who stood out as James Thunder Early in Broward Stage Door’s Dreamgirls, said he really enjoyed the experience but a key adjustment was the lack of an audience. “In theater, we play with the energy of a live audience. You feel very isolated and you become very critical of yourself. You just have to trust your instinct and talent and deliver it the best way you can.”

David Shire and Richard Maltby Jr.’s song cycle was an off-Broadway success whose modest production requirements made it a staple around the country for decades. Without a binding narrative, the songs explore the everyday struggles of love in the modern world. Topics range from unrequited adoration to aging to Muzak. Each song is a unique story told by a new character, taking audiences into the minds of the individuals facing relatable challenges.

One aspect that likely will be watched by other companies is the financing. Over the past seven years, MNM has spent a bit less than $200,000 to mount each of its large cast musicals at the Rinker Playhouse at the Kravis Center in West Palm Beach, charging a $65 ticket.

Closer Than Ever will likely cost about $15,000 to $20,000, Gorman said, because of the limited production requirements, staff and a cast that is non-Equity since the actors’ union still hasn’t figured out how to clear most productions for its members’ safety.

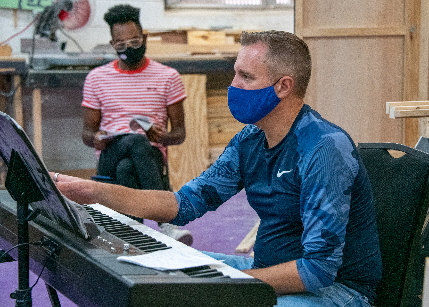

Director Jonathan Van Dyke prepares to clapper the first shot of the production with Aaron Bower

The local actors are being paid roughly half of what Gorman normally pays Equity members for a full run because, among other reasons, the artists’ time invested is about three weeks compared to the five for their onstage run.

Among others working on the project were Cliff Spulock, lighting designer and projections; Emily E. Tarallo, assisting on choreography; Jordon Armstrong, set designer and camera operator; Cindi Blank Taylor, scenic painter; Michael Joseph, camera operator; Justin Lore, wig designer, Amber Mandic and Andrea Guardo, stage managers and props mistresses .

This is not an altruistic project simply to keep the company’s name visible to its regular patrons; Gorman wants to make money. She will charge $20 a ticket for every household since it would be impossible to police how many people are in the living room. MTI, the licensing agency, will take $2 of each ticket and Show4Tix will take about $1.85 of each ticket for providing the cyber platform and ticketing. She’s hoping she can recoup her investment and an equal amount above that.

Looking ahead, Gorman hopes that once shows can return to a live audience, she can reassemble the cast and production in an intimate house. Van Dyke, who thought of the musical that was popular when he first moved to New York City in 1990, expects to see smaller cast musicals become the entry point as conditions ease back to whatever becomes “normal.”

“A lot of this came about as a survival mechanism and I will be forever grateful to Marcie for taking this risk,” Van Dyke said. “It’s do or die (time)…. Each theater has to come up with their something whether it’s zoom or a one-man show or what we did or whatever. It’s just so vital that that everyone — with their own safety measures and their own level of comfort — come up with something to stay afloat.”

“To me, theaters are like churches or synagogues; it’s hallowed ground and we can’t lose them.”

Tickets are available at https://www.mnmtheatre.org/. Once you have purchased your tickets, you will receive a link to view the production. The link will be active for 48 hours from your first click.

Music Director Eric Alsford works with actor Elijah Word

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design