By Bill Hirschman

By Bill Hirschman

“The best of times is now…”

You could be forgiven in cynical 2015 for erroneously writing off the incredulous vision of Jan McArt as some vain diva still living in the heyday of musical theater circa 1959 or 1962.

You’d be incredibly wrong on every count, but it would be understandable.

Even her daughter, Deborah Lahr Lawlor, quipped, “Exclamation points come with her…. Her persona is just bigger than life. She does things in a way that we mortals…,” she paused mid-sentence in wonder.

The First Lady of South Florida Theater could easily rest on a resume spanning Broadway, opera, New York nightclubs, records, singing on national talk shows, stretching back to being hired by Richard Rodgers as a replacement Laurie for a Los Angeles production of Oklahoma.

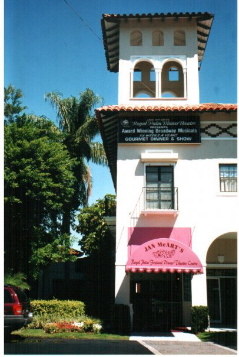

But most significantly, McArt founded the atypically classy Royal Palm Dinner Theatre in Boca Raton and five other venues across three counties – among the handful of pioneers who brought locally-produced professional theater to a region that mostly hosted amateur productions and national road shows.

Its quarter-century run cemented the evolution of the quality and collegiality of the South Florida theater scene, and by extension the region’s cultural landscape.

McArt has an alchemical connection with former patrons who still revere her charismatic aura, and among colleagues who know that underneath is a determined professional who has weathered personal and professional tragedies that encompass fire, near bankruptcy, tuberculosis and death.

And she’ll talk about any of that if you ask. But her total focus is as forward-looking as a college freshman’s. The woman best known for warhorse musicals and boulevard comedies is now deep into her self-described third act: helping local playwrights develop fledgling works for the future.

Speaking from her memorabilia-crowded office, she burbled with effervescence, “New work is the history of theater and new work is the future of theater. I am as excited as I’ve ever been.”

Playwright Michael McKeever, a multiple-beneficiary of the Jan McArt New Play Reading Series, said, “She is not gazing out the windows thinking of her days” gone by. (To see this year’s lineup click here.)

Right now, she is absorbed in producing a staged concert of the classic musical Kismet with 14 actors and a 60-piece orchestra slated for Sept. 26 and 27.

All her projects are based at Lynn University in Boca Raton where over the past 11 years she also created a live performance series featuring opera, jazz and her current cause, cabaret performers. All this has been done in a post she invented, lobbied for and raised funds for: director of theater arts development at Lynn.

“I would put Jan in a class with Harold Clurman, Roger Stevens at the Kennedy Center and Joe Papp,” said Wayne Rudisill, a director of some of the new works. “Jan is sort of fearless like Papp. There’s no turning back. Once she sets her mind to it, she’s going to do it.”

“And make our garden grow….”

Although she has appeared on the national stage and theater insiders across the country adore her, the hard truth is that Jan McArt is not a household name anywhere outside of South Florida. Conversely, nearly everyone working in theater in this region or attending theater in the past 40 years here knows of Jan McArt — and all have been affected by her legacy.

Ask Charlie Cinnamon, the dean of South Florida publicists after a half-century promoting the arts. “It’s a contribution like none other. She speaks to local theater audiences like none other. Nobody defined local theater like Jan.”

Her name alone is still a powerful draw. When McArt produces staged readings of unknown plays still in development, they often attract an audience larger than that for any other similar event in the region.

There are several reasons. McArt was among the first professional producers in South Florida along with Brian C. Smith, Ruth Foreman, Michael Hall, Burt Reynolds and the Coconut Grove Playhouse. Mostly, they only nudged the boundaries of mainstream theater, but they established the foundation for what exists today.

Along with the “next” wave of producers like Rafael de Acha at New Theatre in Miami and Louis Tyrrell at Florida Stage in West Palm Beach, “she was part of that generation that bridged that gap from where there were 10 theaters, now 12, now 20,” said McKeever.

Part of her success lay in the polish and verve she brought to the normally risible category of dinner theater.

“She brought glamour to dinner theater, which was not a very glamorous genre,” said Skip Sheffield, a veteran arts writer and critic. “It’s normally a joke; it’s where middle class yahoos went. But in Boca, it became the posh thing to do. I don’t know if there was another dinner theatre, certainly not in Florida, maybe in the country, that had such a classy clientele.”

But the fact that the Royal Palm and its spinoffs lasted for nearly 25 years also brought a sense that local theater is here to stay.

“You always knew there was a place to perform to work your craft; she created a lot of opportunities for a lot of people,” said Scott Stander, who went from apprentice in Boca to manager of her Key West theaters. “You got paid (little) money, but it did not matter. I would do it again for the experience. There was something magical. There was a team, a family.”

That stability of the Royal Palm and Michael Hall’s Caldwell Theatre Company created a reliable home base for a growing cadre of professionals. “Talented people… moved here to become part of Jan’s world. The area’s talent pool exploded,” Hall said.

She enabled many actors to get their Equity card to solidify their careers. Her assistant Desiree McKim tells of McArt serving on an arts panel recently where the moderator ignored her most of the evening until one panelist mentioned he had gotten his Equity card from McArt. Then one by one, like a rising sea, people on the panel and people in the audience chimed in that, they too, had gotten their start with McArt, even a woman visiting from China.

Another by-product of re-hiring a corps of dependable hands was to forge a sense of community among those professionals, something missing elsewhere in the competitive and ego-driven profession. When McArt asked Hall to join her at the Royal Palm, he declined, citing his commitment to the nascent Caldwell. But from then on, they worked with each other instead of against each other. They shared talent rather than blackballed someone for working at “that other theater.” They strove not to compete with each other’s preferences for types of shows.

That spirit persists in her. When McArt attended the fledgling Plaza Theatre in Manalapan shortly after its inception in 2012, she noticed shortcomings in its sound system, McKim recalled. “She said, ‘I have some equipment I can send over.’ The sound guy didn’t know who she was. She just wanted to help the theater.”

“There’s no business like show business.”

The centerpiece of McArt’s fame is her creation of the Royal Palm Dinner Theatre, a 250-seat venue in the round that operated year-round from 1977 to 2001 without a single break other than rebuilding after a fire.

Unlike many dinner theaters around the country, McArt was determined to make hers an elegant experience with good food and providing as top-notch a production as she could mount – with her headlining 20 weeks out of the year.

Eventually, it had a nearly $3 million annual budget and a weekly payroll with 150 employees, the third-largest operation in the region, tied with Florida Stage.

Eventually, it had a nearly $3 million annual budget and a weekly payroll with 150 employees, the third-largest operation in the region, tied with Florida Stage.

She specialized in mainstream New York fare with large casts, working her way through nearly every classic title. But the Royal Palm also hosted what were then chancy pieces such as Chicago and Stephen Sondheim’s Company. McArt left the bulk of the straight drama field to the Caldwell, but she produced crowd-pleasing comedies and gentle dramas such as Tally’s Folly.

Like the offering at any theater, some work was better than others. But much of it, especially in the 1980s, won critical acclaim. McArt received the Carbonell’s Ruth Foreman Award in 2001 and the George Abbott Award in 1984 for her service to the community. The theater itself racked up by one estimate 278 Carbonell nominations, winning at least 42 awards.

Along with resident director Bob Bogdanoff and business partner Bill Orhelein, she took a cafeteria in a shopping center at 315 SE Mizner Blvd. and created an intimate theater with the audience smack up against the stage.

Behind-the-scenes was as problematic as the stage shows seemed stylish. Audiences grew slowly at first and money was tight. She hired locally because the actors were affordable. The big brassy shows required a full orchestral sound that she could not afford, so she was one of the first to use taped tracks. Bogdanoff told the Sun-Sentinel’s John deGroot in 1988 that in the first year, “We’d go without until the money was there…. But everyone was always paid eventually.”

She had produced shows elsewhere, but this was a huge challenge, she recalled this summer. “The artistic things were the easiest… But you’re also dealing with waiters, bartenders, carpenters, then you have the whole kitchen staff, you have the dishwashers and the cooks and the show staffs. So my payroll ran over a million dollars a year,” she said.

“I am the greatest star…”

Even if you didn’t know Jan McArt was somebody, if you just passed her on the street, you’d know that Jan McArt was somebody. Decades of experience on stage and television have either exploited a God-given charisma or she has developed it herself like her distinctive soprano.

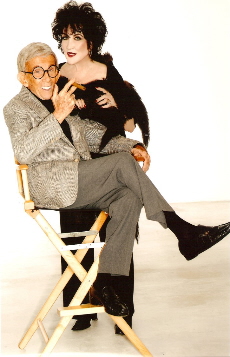

Above all, there’s that look. She only stands about five-foot-four, but you’d swear she was taller. She is always, always — in public, at work, even shopping for Kismet fabric last month at the Festival Flea Market — garbed in stylish clothes, with dangling earrings and perhaps a long necklace. The carefully-coifed raven black hair is teased to look like an explosion in mid-celluloid frame. There’s expertly applied makeup from ruby lipstick to the eyebrows created with a draftsman’s exactitude. It’s often been noted that she resembles the latter-day Elizabeth Taylor.

Friends and fans inevitably describe her today as beautiful. Stander noted, “She’s still breathtaking; those green eyes just melt you, they possess you.”

But an objective observer knows that it’s a lasting inner beauty that mocks inevitable wrinkles and girth. Anyone who doubts the erosion of time need only look at the photographs of McArt in her 20s, 30s and 40s to see what a stunning woman she was.

But an objective observer knows that it’s a lasting inner beauty that mocks inevitable wrinkles and girth. Anyone who doubts the erosion of time need only look at the photographs of McArt in her 20s, 30s and 40s to see what a stunning woman she was.

She has been quizzed about her age in almost every printed interview. She deftly deflects it every time with a quip and a hearty laugh. This year’s parry about her birthdate? “It was before the flood.” Then she takes a well-practiced pause. “But not much.”

Don’t bother trying to look it up. She has at least two cited in public records and reportedly a third. Her daughter, Debbi, who had no problem revealing her own age when she lived in California, said she demurs in Florida because it might be a clue to her mother’s age.

But McKim said it’s more than vanity. “I don’t think she ever thinks in terms of age.” She just focuses on “her vision of what she could do.”

“I am what I am; I am my own special creation.”

The impolite question is whether that outsized glamorous creature is genuine or an exterior put on for the public. Is Jan McArt for real? Generally, people who have worked and socialized with her will echo actor pal Jay Stuart: “That’s the real Jan McArt; what you see is what you get,”

But a few say that persona was constructed. “She built herself,” Lawlor said. “I don’t think it’s deliberate. I think she has wanted to define who she is as she goes and I don’t think it’s necessarily analytical. I think there’s an impulse. I don’t think there’s a lot of pre-thought and forethought that goes into it, by any means. It just evolved.”

Sheffield, who became a good friend, has a journalist’s skepticism. “The fancy Jan is entirely an act. She is just a plain ordinary girl from Indiana, and the rest is just fabrication. I love her both ways.” He recalls meeting her for a first interview in 1977. “I was impressed how plainspoken, how Midwestern and genuine she was because her PR people had built her up as this big opera star from New York.”

In fact, there is someone under the charming gregarious performer. Colleagues credit her as a dedicated, collegial hard-worker who comes to rehearsals fully prepared, absent any shred of diva behavior.

She might seem confused for a moment in rehearsal, McKeever said, “but as soon as she steps on stage… she knows when the audience is with her, knows when the audience is not with her, knows how to get them back.”

She takes seriously the responsibility of being “Jan McArt,” colleagues said. “She realizes that her name is on the product and it is representing her,” McKeever said. “She knows that Jan McArt is not just a person, but a brand, that she is someone people will come to see.”

There may be glamour but there are no pretentious airs that she is above the rough and tumble of running a theater. Sheffield recalled, “I have seen her backstage at the dinner theater when she put her hair up in a babushka and literally cleaned toilets there and mopped floors.”

She is not as detailed-oriented as she might be, but she has a strong sense of the big picture, intimates said.

Above all, she has an infectious enthusiasm. “She has people who want to help her,” Lawlor said, “They want to make her dream come true and her vision because she paints a beautiful picture and… they want to come along for the ride. That’s how she’s had investors over the years; they want to come along for the Jan Ride.”

Driven by her vision, she can be impulsive, Rudisill said, but “I’ve never seen Jan angry, which is very unusual for someone in the theater. She keeps everything on an even keel. McKim said that she actually has a “thin skin, but I think it’s not in her nature to hold a grudge. She makes excuses for them. She forgives.”

But, still, she is not the most introspective person. Asked what drove her to perform from childhood, she answers with a verbal shrug, “I just wanted to do it from day one. I don’t know really because it just seems like second nature to me.” Even now, she vocalizes warmups in the car just as she used to do driving to gigs decades earlier. The once liquid soprano voice is huskier and craggier, but “It’s habit, routine, delight. I don’t know what else to do.”

Lawlor smiled quietly at that. “That’s not totally it. I think she likes what she gets back. Adoration and admiration, I think that’s very very important to her. But she probably doesn’t admit that. Not that she’s keeping it from you, but she doesn’t think deeply about it.” What keeps McArt going through her third act is her sense that “life’s an adventure and she has not lost that one bit.”

But other than confidence in her skills as a theater-producing businesswoman, McArt has doubts. Is there anything she’d do differently in hindsight? “Oh, everything. I wish I had done everything better. I could do everything better now, because I know more…. I mean motherhood, wifehood, singing, going after work, running things.”

For someone committed to a time-jealous profession, family remained a significant part of her life. She shows the framed photo on her desk: McArt as a child alongside older brothers, Bruce, who became a surgeon (“We called him a cut up”) who died last year, and her soulmate Don, known to her and their friends as Bunny. His death in 2012 after a lengthy battle with cancer is rated by friends as one of most shattering events of her life.

The elfin Don McArt also made a life on stage with a few credits in film and television. He worked often in his sister’s productions and enjoyed a late-in-life tour as George Burns in the one-man play, Say Goodnight, Gracie.

He was her adviser, her mentor. He was the one who talked her into cornering Richard Rodgers. They spoke nearly every day. But he also had a concurrent career as a minister of the Science of the Mind Church as a channel for his positivity that clearly influenced his sister.

“He got her through” the tough times, Stander said. “When the Royal Palm closed, he was her rock, he was by her side. I think he’s still around her, floating. He’s still guiding her.”

But she rarely has lacked for someone close by. She was married and divorced twice, and had several beaus and significant others such as business partner Bill Orhelein.

She remains close to her daughter who McArt raised in New York after the first divorce, with her own mother babysitting when McArt had to tour. Lawlor is now a realtor, but she is also a theater lover. Although she has a fine singing voice on display in local chorales and helped manage the Little Palm Children’s Theatre, she never felt compelled to compete with the force-of-nature that is her mother.

“People, people who need people…”

Someone somewhere must have a harsh word to say for Jan McArt. But you’d have to be an investigative reporter with a lot of free time to find them.

One key to her success as a performer, certainly her success as a fund-raising rainmaker, has been her preternatural ability to connect with people from busboys to doyennes. Her genuine interest and caring is returned with undying affection from her fans and loyalty from her colleagues.

She makes them “feel they are the only person in the universe. She can focus as if you are the only one in world that she cares about, because at the time it’s true,” said cabaret artist Deborah Silver.

The symbiosis manifests itself daily as people stop her on the street, in the market, even on a cruise ship. When you are out with McArt, Rudisill said, “You might as well stand off to the side because she has that magnetism that attracts people.”

Lawlor remarked, “She kind of gives people a shot of like B12…. I think it’s her joy of life that people get out of her.”

McArt communicates her interest by absorbing details of your life and mentioning them in conversations months, even years later. It extends to her habit of writing notes, such as acknowledging hundreds of condolences when Don died.

But the adoration from fans is nothing compared to the devotion of people who have worked with her. Scores turned out to a public reception in 2012 and just as many at a private reunion in 2014. There’s even a “We Worked At The Royal Palm Dinner Theatre” page on Facebook with 330 members.

Stander, now a talent manager, received his theater education by her example: “She never screwed anybody. What she did in the early days when she knew she couldn’t pay what other bigger operations could, she made people as comfortable as she could, threw a pizza party in the bar, or she took people on a boat because she knew a gentleman who had a boat.”

Years later, “people would come up to her in restaurants and say, ‘You turned my life around when I was a chorus girl and you gave me encouragement,” he said.

When an opera company came to Lynn, McArt asked the leading diva how the accommodations were. “Well, the woman said they were hot, the air conditioning wasn’t working and other things,” McKim recalled. “Jan invited the entire cast, not just the leading lady, to her house to use the pool, and she made them food, and let them all take a shower there. She takes care of her people, and not just to get the best performance out of them, but because she knows what it’s like.”

“Good times, bum times, I’ve seen ‘em all, and my dear, I’m still here.”

She loved portraying the last word in joie de vivre in Mame, but some observers say the role that fits best is the indomitable survivor in The Unsinkable Molly Brown with her rousing anthem, “I Ain’t Down Yet.”

Under the glam is iron. Her litany of heartbreaks would give anyone pause: two divorces; Orhelein’s death from cancer in 1987; frustrating efforts to start theaters in Key West; the death of her mother in 1991; the 1993 fire that shuttered the theater; its faltering finances in the early 1990s; the 2001 death of artistic partner Bogdanoff; the decision by her board of directors to close the theater soon after; the death of Bruce in 2014, and probably the most crushing, the death of her beloved Bunny in 2012.

A word that comes up repeatedly in interviews is resilience. “When she went through her darkest hour, which was when the theater was closed, a lesser person would have maybe decided maybe it was time to retire,” Sheffield said. But instead, she resurrected herself.

McArt acknowledges it, but in a self-deprecating way. “I think everybody in the world, unless they are very, very lucky, have faced challenges of different kinds. So it’s not that I have had more than most.”

She unleashes a trademark laugh. “Everybody thinks that you’re so brave about coming back, but basically what else can you do?… I guess I’m the eternal optimist then because I always know that everything is going to work out all right.”

She exudes an overwhelming positivity. Anger, she believes, is a waste of time; she consciously backs away from negative situations. “We won’t even touch that stuff; it’s not for us. It’s gossip, it’s stuff we don’t even care about.”

Several observers, herself included, credit some of that to a non-proselytizing spirituality, some of it nurtured by Don. Her daughter said, “There is the sense of believing there’s always something next, not necessarily knowing what it is, but knowing that she’s going to land on her feet.”

She stumbles and grieves, but few see it. “She goes home during the tough times and regroups,” Lawlor said, “but it’s done quietly and silently within her. It’s very private moments. But I’ve never seen her – she’s not one to fall apart. She probably gets quieter and less social for a period of time. “

Then she rebuilds those inner reserves. “She has had a lot of things happen to her but you wouldn’t know that because it’s not in her history that she has rewritten for herself. It’s totally edited out. And she feels that. It’s not intentional. I might refer to the bad things that could have happened and she’ll go, ‘It did?’” Lawlor said.

McArt agrees only in a sideways abstract answer, “I would probably tend to keep any bad news to myself.… Maybe when I’m feeling, I don’t know, inadequate in some situation. I’ll sit down and maybe I’ll read my resume and think, ‘Oh, yeah, that was good,’ and I guess I’m okay…. Every time I’ve had had any real trouble, I have almost invariably found that it’s been a lack of gratitude.… I’ve got health, I have a lovely dog, and I have a lovely boyfriend, I have a house, I have a beautiful daughter…. Other than that, you’re so busy trying to do whatever you’re doing that you don’t really think about what you have done.”

Enter Laughing

The curtain raised for Janice Jean McArt near Cleveland on Sept. 26 in a year it seems churlish and useless to ask about. She moved to Anderson, Indiana when she was three or four years old when her father, an engineer with General Motors, was transferred. She and Don seemed bitten by the performing bug in their cribs.

She studied drama and music for two years at DePauw University, but her heart wanted to follow Don who already had begun a career in the outside world.

In her late teens, she married Phillip Lahr, brother Bruce’s roommate in medical school. He became an Army doctor and was sent to Korea while she waited for in California near Don, who was trying to make his way in Hollywood. She stayed to the disapproval of her parents.

Don knew that Rodgers and Hammerstein were in town casting replacements for a production of Oklahoma playing in Los Angeles and headed for the road. Tipped off by a friend, they cornered Rodgers as he left the Brown Derby restaurant. Rodgers brought her to the theater, she sang “Some Enchanted Evening” (which legend has it Rodgers had to inform her that he had written), and he cast her as what she says was the first brunette Laurie.

The ensuing journey is a kaleidoscope. She was a chanteuse in clubs and concerts in Japan and Germany where Lahr was stationed and later tony supper clubs from Bangkok to London to New York City. While in Germany, she virtually lost her voice to tuberculosis in her lungs and spent a year bedridden. Then she battled to rebuild her soprano.

She undertook opera training and later sang regularly with the San Francisco Opera and the NBC Opera. She embraced broadcasting and sang pop music on The Merv Griffin Show, The Mike Douglas Show and The Tonight Show. She produced club shows that she took out on the road, and worked alongside Liberace and Jack Jones. In the mid-1960s, she played Broadway as a stand-by for Janis Paige in Meredith Willson’s Here’s Love, appeared in an off-Broadway revival of The Golden Apple and as Princess Aouda in a musical of Around The World In 80 Days at Jones Beach. The list goes on and on with vocal coaching, television commercials, and performances with orchestras around the country.

There was a price. The marriage disintegrated because as supportive as Lahr was, McArt acknowledges, this was not the life he had envisioned. The union had produced Debbi who made McArt a grandmother a generation later. When McArt was deep into her cabaret career later, she married Life magazine photographer Carroll Seghers II, but that, too, fell victim to the demands of her career.

“Take my hand, I’m a stranger in paradise.”

Then the unexpected: “I came down here like everybody else – to visit my mother,” McArt said. Her widowed mother had retired to Boca, a few miles from where McArt’s grandparents had vacationed regularly in Manalapan. She knew the region because Don and New York friends had played here.

In the summer of 1977 McArt was performing at Sarasota’s Golden Apple Dinner Theatre so that she could visit her mother on theater-dark days. An idea blossomed: “I thought I’d start a little business so I could come down from New York and look in on my mom every couple of weeks, and my accountant will think I’m smart because I can write off my trips.”

She found a cafeteria in the flower-bedecked pink-tinted Royal Palm Plaza shopping center. “So I just walked in and said to the guy, ‘Have you ever thought of selling?’ He had a manifest… and handed it to me so fast I should have been suspicious.”

Around February, she put down $25,000 with the intent to raise the rest by October. Her significant other Orhelein moved down from New York to run the finances and adjacent restaurant.

“I thought I’m not going to have any trouble raising money here; there’s money here obviously, and I’m a nice person…. So time goes on. I have to come up with the rest of the money. We’re coming into the fall and I hadn’t raised a penny….So now I’m really stuck because I’m committed to this place.”

“I thought I’m not going to have any trouble raising money here; there’s money here obviously, and I’m a nice person…. So time goes on. I have to come up with the rest of the money. We’re coming into the fall and I hadn’t raised a penny….So now I’m really stuck because I’m committed to this place.”

They managed to open in December 1977 with McArt starring in one of her favorite shows, a condensed version of Franz Lehar’s operetta The Merry Widow. From then on, it was back-to-back productions 52 weeks a year for nearly 25 years with McArt taking on virtually every major role in the musical theater canon.

It required the acumen of an accountant, the pragmatism of a producer, an evangelist’s ability to hypnotize donors, and the well-honed chops of a performer. For a profession that breeds egotism, it also required a selfless willingness to get your hands dirty.

“I was doing Julie in Showboat. I had a gorgeous green outfit. We’d done a matinee and they came out and said the dishwashers have gone out on strike, and we were sold out, and we had a show that night. I took off my green velvet dress. I still had all my good jewelry on.” She and a waitress “did all the dishes… and then I put the green velvet dress back on and the hat and then, ‘Fish gotta swim, birds gotta fly. ’”

The first months were not terribly successful. She had planned on operating the theater long distance, popping in occasionally while keeping her New York career on its upward trajectory.

“We were going broke pretty fast.” She sold her Central Park West apartment and a 10-acre retreat in Connecticut. “It occurred to me that if I was going to raise the money, I didn’t really want someone else running it. So, okay, you’re going to get a doctorate in running a theater.”

Once on the ground, she and Orhelein found the groove. McArt says she’s not good at remembering dates, but she remembers the turning point: August 25, 1978. A production of The King and I hit paydirt. Her clientele grew to span the region geographically and socially, snowbirds and locals, youngsters and seniors, entire families.

During the heyday, the scope expanded. Her main location added the Little Palm Children’s Theatre, the Rooftop Cabaret Theatre and an outdoor cafe. She mounted a season of a Festival Library Theatre inside the Main Library in Fort Library and another in the basement of the Marco Polo hotel in Miami Beach.

She also made a beachhead in the mid-1980s in Key West. Years of planning to renovate the San Carlos Opera House cratered when Cuban-Americans objected to a theater housed where Jose Marti had spoken. But with the on-site management of Stander, they took over a city-owned warehouse in Mallory Square and staged such shows as John deGroot’s Hemingway bio-play Papa starring Bill Hindman. She poured a lot of money into the theater, but problem after problem doomed the project.

In the wake of Joseph Papp’s success with a pop The Pirates of Penzance, she mounted her own version with BeeGee Andy Gibb and then-hot Barry Bostwick in three separate national tours. Then she put together a touring edition of Jesus Christ Superstar with General Hospital heartthrob Anthony Geary. She even produced the new musical The Prince of Central Park with mixed success locally, and a disastrously short run on Broadway in 1989.

The theater’s fortunes soared until April 14, 1993. A cigarette smoldering in a booth erupted into an overnight blaze. Flames and smoke wreaked an estimated $500,000 damage.

“You put one foot in front of the other. There’s no time to be emotional about anything because you have to ask ‘How am I going to do this? I’m not going to let this go down the drain.’ So I gotta do it. So you do it,” she recalled.

Six months of renovation later, the theater was back in business. But it required exhausting the company’s entire cash reserves plus a $1 million loan. The theater never again made a steady net profit and never recovered fiscally.

The toughest part of running the theater was never the art, she said. It was “the bankers, having the cash flow to do what you had to do.”

Finally, she made the company a non-profit operation in 1998 and took on a board of directors –a fatal move. “It was different from when I was kind of the sole owner and manager; you couldn’t make decisions unilaterally like you did when you owned it,” McArt said.

Less than two weeks after the death of resident director Bogdanoff in 2001, the board decided the finances were insupportable and they voted to shut it down in April.

McArt did not surrender. She, Don and Debbi took to the telephones trying to raise the $100,000 it would require to continue. Friends and colleagues kicked in, such as the late producer Jay Harris. But they could not reach the goal.

For the first time in her life, the show did not go on.

“Another op’nin’, another show…”

Standing still was impossible. The very next year she began a new campaign. She suggested a concert series to Donald Ross, then president of Lynn University. He gave her $10,000 seed money but said it was all on her. Oh, and could she tackle a broader mission as Director of Theatre Arts Program Development?

“I came here, they gave me a pencil and a paper and a computer which I didn’t know how to use and a telephone. So then I kind of cut my path to fit and that’s been very, very creative,” she recalled.

“I called in every favor in the world,” she said, but the crucial boost occurred when relatives of the late Libby Dodson said the woman had been a big McArt fan. They donated $500,000.

The subsequent Libby Dodson’s Live At Lynn series of concerts from classical to jazz impressed Lynn patroness Elaine Johnson Wold who, for several reasons, funded construction of the lushly-appointed Wold Performing Arts Center that McAct is now ensconced in along with several of the college’s musical education programs.

Another linchpin event occurred in 2011. Fellow theater veteran Iris Acker suggested that her friend Tony Finstrom had a radio play that might benefit from a reading in front of a Lynn audience, Murder On Gin Lane.

McArt was so energized that she created a permanent series of readings “because I can see it happening before my eyes. You know I was always a live performer. You get out there and get the applause right then. That was very satisfying to me. I like to be able to see something happening as it goes, and I can see it with the play readings.”

Since then, the program has developed about four plays a year. Unlike most staged readings in the region – one-day affairs for little or no compensation with actors standing in front of music stands – McArt hires local A-list actors working for Equity scale for six solid days and ending with some staging, minimal costumes and props. The script changes daily based on what the playwright hears in rehearsals.

It’s an invaluable paradigm, said McKeever, who has performed in four of the readings and had two scripts produced there. His Daniel’s Husband about gay marriage went on to a triumphant world premiere several months later.

There’s more projects in the wings, McKim said, suggesting that McArt doesn’t seem to need sleep. Rudisill added, “Right now she’s trying to build a cabaret series, and I keep saying Jan, ‘Cabaret is dead or it’s not going to be back for a while.’ But she says she has faith in it, she believes that she will build a following.”

Plus, Kismet, starring her old friend Jay Stuart as the wily beggar Hajj set in an ancient fairy-tale Baghdad. “Kismet, from beginning to end is my vision…. I’ve been involved in everything from Jay’s beard to making cushions for the stage. It’s very much ‘let’s build a barn and put on a show.’ ”

Stander isn’t surprised, “When I think of Jan, I always think of forever. She’ll always be forever, in this life we’re living and from then on.”

But she’s relentlessly focused on today. “The Palm Beach Post said I was one of the 100 most influential people in the last century here. So I realize I definitely did change the cultural landscape here…. But you’ve got to remember that I’m still trying to do stuff. So I can’t be thinking of about what I did do, because it’s what I want to do next. “

Sit back on her laurels? ”I don’t believe it’s in my nature. I think I will go to the great theater in the sky directly from this office. Or the stage. But not too soon.” And then there was that laugh.

Kismet will run at 7:30 p.m. Saturday Sept. 26 and 4 p.m. Sunday Sept. 27 at the Keith C. and Elaine Johnson Wold Performing Arts Center on the campus of Lynn University, 3601 N. Military Trail, Boca Raton. Tickets $70 box, $55 orchestra, $50 mezzanine. Call (561) 237-9000 or visit events.lynn.edu.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design

9 Responses to —— Open A New Window —— –The Three Acts Of Jan McArt–