UPDATED

UPDATED

By Bill Hirschman

The Miami City Commission agreed Thursday to delay a meeting on what many believe is the last crucial decision regarding the future of the Miami-Dade County proposal to resurrect the fabled Coconut Grove Playhouse.

The commission agreed to hold a special meeting devoted solely to the topic at 9 a.m. May 8 at City Hall. County Mayor Carlos Gimenez had suggested the meeting be deferred only a week, but city officials had scheduling conflicts.

The agenda item slated for Thursday would have either critically derailed or cleared one of the last hurdles for a proposal from the county, Florida International University and regional theater GableStage to build a 300-seat theater and educational facility on the site where the 1926 building has sat deteriorating since it was shuttered in 2006.

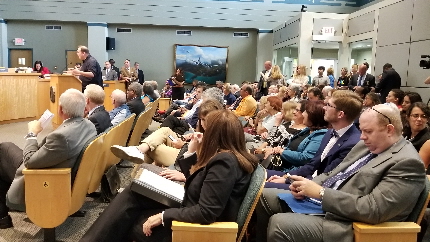

The decision came after a 90-minute public comment section with 40 speakers at a standing room only session and with people in the lobby wanting to come inside to testify – a seriously divided audience of theater professionals, long time Grove residents, lawyers, architects, business owners, politicians, arts patrons and preservationists. Many argued against the delay, saying the process already had taken years too long; others contended a delay was necessary to have sufficient time to contradict alleged misinformation and disinformation about the project.

The origin of the delay was deference to a letter written Wednesday from U.S. Rep. Frederica Wilson-D to Commission Chairman Ken Russell. While the neighborhood is not in her district, she cited her interest in her capacity as Honorary Chair of the Bahamian Heritage Initiative. The Playhouse property is bordered on one side by the Grove retail-entertainment district and on the other by a primarily African American neighborhood. A few people testified Thursday to say those neighbors’ concerns hadn’t been sufficiently addressed.

Wilson wrote, “…this matter is of extreme importance to me. I have been in communication with several members of the community regarding this issue and would like the opportunity to be briefed as well as to participate in the upcoming public hearing.” She wrote that her schedule did not permit her to briefed in time for the meeting.

But theater director Gail Garrisan echoed other speakers, “Where has the Congresswoman Wilson been for the last ten years?… (A delay) is unconscionable and insulting.”

County Mayor Gimenez, a long time champion of the county project, testified that he was not happy about a delay, but he was the first to suggest setting a final time-certain concrete date in the future. He said it has been unfair to the scores and scores of citizens who want to speak on the issue to repeatedly take time from work and family to come to the long series of meetings and hearings that already have taken place.

He also warned that value of the voter-approved bond issue funding for the project decreases every day as construction prices increase.

Some city commission members like Manolo Reyes also expressed frustration at the long tortuous path the project has taken. Some including Mayor Francis Suarez expressed interest in independently proceeding with a pending parallel project to build a parking garage adjacent to the theater, but on the same piece of land owned by the state. But the city parking authority official advised that the current lease for the land tied the two projects.

The nationally known Playhouse has been closed since its 50th anniversary season when an estimated $4 million in debts caused its non-profit board to shutter operations. But arts and county officials led by Michael Spring, director of the Department of Cultural Affairs, had been striving for years before that to preserve some kind of theater operation on the site.

Since then, they developed the current plan to build a 300-seat theater plus space for college classes on the property on the corner at 3500 Main Highway in Coral Gables. The cost would have been underwritten by $23.6 million in on-hand funds, mostly from the bond issue. County officials had said that construction could begin this year if no other problems arose.

Technically on Thursday, the city commission was supposed to consider the county’s appeal of the city Historic Preservation Board’s decision to oppose the county’s proposal. That preservation board had initially approved the project in 2017, but reversed itself March 5 following a lawsuit filed by two Grove residents.

The county’s appeal has little to do with the architectural, artistic or fiscal issues, which it considered settled in a city commission vote two years ago. The county’s legal documents accused the Preservation Board’s Vice Chair of “hijacking” the March meeting, having “conspired” with opponents, and inserting incorrect criteria into the board’s deliberations.

But City Commission Chairman Russell said during a break in the meeting that while the board must consider the technical legalities of the appeal sitting as a quasi-judicial board, it will have the right to consider broader underlying issues up to a point at the May 8th meeting.

Yet another complicating factor is the 2013 lease that the county and FIU have with the state, which owns the property. The deal can be canceled if “construction is not completed” by 2022, said Scott Woolam, senior project manager for the Division of State Lands for the Department of Environmental Protection, on Wednesday. The county has not formally responded yet to a letter sent last year requesting reassurance that project will be completed by then, Woolam said.

The county plan proposes renovating the iconic façade of the existing structure and the “front building” facing the street, which would house offices and possibly retail outlets. It would also build a small courtyard behind it; plus tear down the deteriorating auditorium and replace it with the new theater. The City of Miami would build an adjacent 500-slot parking garage to be used by the theater, FIU, local businesses and nearby public schools; the structure might also house residential apartments and retail stores. Some of the revenue would help pay for the initial operating expenses of the theater. The plans also acknowledged that perhaps a larger theater could be built adjacent to the smaller venue in the future.

The project is to be paid for with $5 million in proceeds for Convention Development Tax Bond approved by voters, $15 million from proceeds of a

Building Better Communities Bond, $1 million from the Convention Development Tax, $2 million from a Knight Foundation Grant, and $600,000 from parking in an adjacent garage to be operate by the city parking authority. County commissioners have repeatedly affirmed their support, but have been equally adamant that they would not spend an extra dime on the project. Some leaders felt burned that the construction and initial operations of what is now the Adrienne Arsht Center ran way over projected budgets requiring county tax support.

A Bitter War

But the proposal has been embroiled for years in a tumultuous and protracted fight that has encompassed fund-raising, polls, contradicting studies, contracts with consultants, public hearings, rallies and copious impassioned social media posts.

The opposition fell into two main groups:

—One group, loosely connected under the organizational banner Save The Coconut Grove Playhouse, wants to preserve what they contend is an architectural landmark. The building was formally recognized as a “historic site” by the City of Miami in 2005, meaning it cannot be altered or torn down without city approval.

The three-story edifice was designed as a silent movie house in 1926 in the Spanish Baroque “Mediterranean Revival” style by Kiehnel and Elliott Architects, and reworked slightly when a hurricane damaged it soon after. Unlike many movie palaces of the era such as the Fox Theater in Atlanta, the interior was not unusually ornate. The application for preservation status called it “a noteworthy expression of the Florida Land Boom” whose “original design by the critically important architectural firm of Kiehnel and Elliott…. embodies the metaphoric Boom and Bust cycles that Florida has experienced, and continue as a signature building reflecting the heyday of Coconut Grove.”

—-Another group – some of whose members also belong to the first group – believe that the GableStage proposal is too modest. That group, whose most outspoken voice is philanthropist, lawyer and arts activist Lewis “Mike” Eidson, prefers a 700 to 900-seat theater akin to major regional theaters like the Alliance Theatre in Atlanta or Actors Theatre of Louisville. One operational option would be a private-public partnership like the Arsht Center, which Eidson chaired for some time.

Eidson, who created and funded a Coconut Grove Playhouse Foundation, has said frequently that this site provides a rare forward-thinking opportunity to help Miami become a world-class nationally-recognized arts center. He did not return emails or phone calls for comment this week.

But supporters of the smaller theater have argued back:

—Little of the original design lauded by preservationists still exists. The county hired architectural history expert Jorge Hernandez who confirmed that the building had been renovated and altered repeatedly, most notably in 1955 when the auditorium area was overhauled to accommodate stage productions, even including a balcony. The lobby and other areas were also altered. Another study found layer after layer of different colored paint going back to a golden hue from the building’s earliest days. Even the façade was changed, seen by comparing photographs from 1926 and 1971.

—Detailed analyses of the building’s structural integrity indicate that even if the building was in good condition, the structure would not meet current building codes required to allow anyone to occupy it, county officials have said. County reports unreel pages of specific citations of rotting roofs and cracked concrete eroded by seawater used to mix the concoction — all of which would require more money to correct than is available through the bond issues. That confirmed what former employees and others who have been inside have said: The facility was literally falling apart even before financial problems caused the theater’s board of directors to shutter the structure. Some opponents disagree, saying the building’s condition is not as dire as is being portrayed and could be reclaimed.

—Some local theater professionals and some national consultants doubt that a 700 to 900-seat theater can be self-supporting, even with grants and donations. South Florida institutions have found traditional theater a harder sell in recent years. They say the older generation that was once the mainstay is dying off, younger audiences are hard to attract, Miami’s dominant minorities do not attend classic mainstream theater in the numbers that producers hope for, and like the rest of the country, season subscriptions locally have fallen off in favor of undependable spur-of-the-moment decisions to attend a show at most venues.

—The state, which actually owns the property, has signed a 50-year lease specifically with the county and FIU, with two 25-year extensions possible. That 2013 lease specifically cites a 300-seat theater and a proposed self-sustaining operating budget for the modest facility, Spring said.

The History Plays

The delay is just one chapter in years of controversy. The county has invested thousands of hours into the project including paying $1.3 million to designer Architectonica, its subcontractors and other consultants to develop what they claim are plans ready to submit to the city’s building department for a construction permit and then to go out for bid.

For more than three years, Spring, GableStage Producing Artistic Director Joseph Adler and other players have met by telephone almost weekly to discuss logistics, design and financing.

Adler has spoken to his board about needing more diverse members, more members who can raise funds, the eventual need for a larger staff since GableStage operates with a tiny cadre of employees, and even a long-term succession plan for the Playhouse leadership.

Guiding the project through the gauntlet of elected boards and appointed committees has been exhausting. Negotiations, hearings and meetings have dealt with citizen groups, business leaders, the Miami Parking Authority, three other city of Miami boards and the state Department of Environmental Protection which supervises the property owned by the state.

That includes the complex but pivotal events leading to Thursday’s vote. The odyssey began when the city’s Historic and Environmental Preservation Board approved the county’s master plan April 4, 2017. The only asterisk was the board asked for more detailed plans about the reconstruction.

Subsequently, two Coconut Grove residents appealed the decision.

On March 5 this year, the county returned with the updated plans as requested. The city’s Preservation Board, including some new members, voted 6-4 to deny the county’s application. The decision overruled its own staff’s professional recommendation, a county website contends.

In its appeal on Thursday, the county accused Preservation Board Vice-Chair Lynn Lewis of “hijacking” March meeting and having “conspired with objectors outside the public hearing. Further, it claimed that Lewis insert(ed) inapplicable and erroneous standards into (the Board’s) consideration” thereby “violat(ing) fundamental guarantees of due process and cause (the Board) to depart from the essential requirements of the law.”

A key issue helping lead to the board’s reversal at that second board meeting was challenging the idea of demolishing the interior of the building. The county argued in its appeal both to the court that the board had already approved that aspect of the plan in 2017; the second hearing was supposed to focus on the new drawings the board had requested the county bring.

In December 2017, the city commission overturned the preservation board’s decision but imposed additional requirements on the project. The County appealed in court. Last December, the Appellate Division of the 11th Circuit Court issued a unanimous ruling in favor of the county’s position that the people filing the lawsuit did not have standing to file the appeal. It overturned all of the city commission’s conditions, including that the shell of the existing auditorium be maintained.

The Coconut Grove Playhouse has played a major role in Florida cultural history. In the 1950s; it began a history as one of the nation’s leading regional theaters that emerged after World War II. In its heyday, producers like Zev Buffman, Robert Kantor, Jose Ferrer and, after 1985, Arnold Mittelman mounted their own shows, hosted national tours and even provided a home for works being developed for Broadway.

The shows and the performers reflected a time when fading stars and supporting actors in film and television were able to headline major stage productions that they would never have the chance to attempt in New York. Some were triumphs and many were flops. Some were unadventurous fare; others reflected the latest thought-provoking hit from Broadway.

Among the legendary productions were Tennessee Williams himself directing Tallulah Bankhead in A Streetcar Named Desire. Another was the first American production of Waiting For Godot, starring Tom Ewell and Bert Lahr, an evening that left many playgoers confused because it wasn’t the comedy those stars were usually seen in.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design