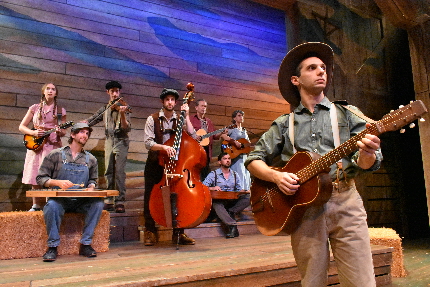

The cast and musicians of Woody Guthrie’s American Song / Photo by Cliff Burgess

By John Thomason

Had Woody Guthrie, the hillbilly godfather of American folk music, lived to see his songs become the foundation of at least two stage musicals, he probably would have been bemused. During his Depression-era travels as a penniless troubadour, from the Oklahoma Dust Bowl through the promise of California, there were, as now, two Americas. And Broadway entertainment, with its professional lighting, its sprung floors, its assigned seating, was the realm of the moneyed class. By the time Woody wound up in New York City, he planted roots not at the Waldorf but on the Bowery, where Kafka-sized cockroaches scurried about the flophouses.

Yet the earliest of those Guthrie musicals, Woody Guthrie’s American Song, is most decidedly a people’s musical, at least in its vivifying production at Palm Beach Dramaworks. Comprised of Woody’s songs and writings, as conceived and adapted by Peter Glazer and arranged by Jeff Waxman, the show premiered in 1988, and it doesn’t show a lick of its age. Under Bruce Linser’s loose-limbed direction, it’s neither revue, nor Guthrie biography (Woody Sez, the other Guthrie show, fulfills that function), nor jukebox musical. It’s more of a communal hoedown with Guthrie’s music as the soundtrack. Even the songs about poverty, death and hard living hide notes of hope, if we can only come together to find them.

This sense of oneness is evident from the production’s prologue, in which its five actors each begin to tell Woody’s story, only to be interrupted by their castmates, creating a barn of babble. When everyone’s talking, no one is heard; it’s only when they erupt in song, a glorious rendition of “Hard Travelin’,” that they find harmony.

To the extent that a plot exists, Woody Guthrie’s American Song begins with the singer-songwriter’s formative years on the Oklahoma plains in the early 1930s, follows him as he jumps the rails to the west coast, and settles in for an extended sojourn at a “jungle camp” in California, where jobless laborers have carved makeshift homes out of the open space, singing about opportunity and its absence. The second act is primarily set in a Bowery bar in New York City in the 1940s, where Woody busks for rent money, the specter of World War II looming just over the horizon.

Three of the actors are and aren’t Woody Guthrie. They adopt first-person narration between the songs, but they double as ambient supporting players in Woody’s journey, eager to gift the Guthrie avatar to the rest of the ensemble. There’s Jeff Raab, who channels Guthrie’s earliest pangs as a balladeer; Sean Powell, who projects the cockeyed optimism of Woody’s west coast travels; and Don Noble, who brings a sage wisdom to Woody’s final years. Cat Greenfield and an aged-up Julie Rowe may not embody Woody directly, but they’re no less important to the production’s success: Their stirring, honeyed harmonies on numbers like “I Ain’t Got No Home in This World Anymore” and the mesmerizing “Ludlow Massacre” are among the most beautiful and evocative in the show.

Yet critiquing the quality of acting in Woody Guthrie’s American Song almost misses the point, in part because there’s so little of it. But there’s a lot of music: All five actors play their own instruments—a prairie goulash of guitars, mandolins, banjos, fiddles and more—alongside their onstage backing band, local bluegrass trio The Lubben Brothers. This production collapses the distinction between actor and musician, relinquishing egos to the greater hive mind. Everybody’s one, remember?

In that sense, it’s more of a director’s show than an actor’s show. Despite the countless moving parts, Linser has captained a seemingly effortless ship of song, lending the production the breezy air of an informal jam session. Players reappear before we realize they had departed the stage; costume and instrument changes flow as fluidly as a lazy river. The dynamic Michael Amico set begins as a barn, and, before we know it, it’s a rattling train car, then a furnished shantytown, then a dingy pub. For a show that is essentially a patchwork of people, places and songs, we never see the stitching.

If there’s one misstep that disrupts the trance, it’s when the actors jump off the stage and invite front-row patrons, however briefly, to dance with them, a move straight out of cruise-ship revues. (I prefer the sentiment Linser himself expressed in The Wick’s Drowsy Chaperone last year: “And keep the actors out of the audience. … I didn’t pay good money to have the fourth wall come crashing down around my ears.”)

Undergirding the experience is the remarkable timelessness of Guthrie’s lyrics. American Song arguably avoids the most-political protest songs of his career, as much as I would’ve loved to hear a new arrangement of his rousing directive to “tear the fascists down.” But today’s headlines haunt the show nonetheless, from attacks on unions (“Union Maid”) to predatory finance (“Jolly Banker”). Greenfield’s stunning performance of “Deportee (Plane Wreck at Los Gatos)” captures the dehumanization of illegal immigrants that’s essential to Trump’s border policies: “Is this the best way we can grow our big orchards? Is this the best way we can grow our good fruit? To fall like dry leaves to rot on my topsoil / and be called by no name except ‘deportees?’”

Yet, as the show reminds us, we cannot fall into malaise. Woody kept fighting, even when the world seemed its bleakest. During “End of My Line,” Don Noble, as a homeless jungle camper, reaches the end of his. He breaks down mid-song and hangs his head in despair—until Greenfield and Rowe comfort him, transforming the song’s title sentiment into one of resistance, not resignation. We’ll get through it, together.

Woody Guthrie’s American Song runs through Aug. 5 at Palm Beach Dramaworks, 201 Clematis St., West Palm Beach. Show times are 7:30 p.m. Thursdays, 8 p.m. Fridays and Saturdays, and 2 p.m. Saturdays and Sundays. Tickets are $75, and Pay Your Age tickets are available for spectators age 18-40. Running time is 2 hours and 30 minutes including a 15-minute intermission. Call (561) 514-4042, or visit palmbeachdramaworks.org.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design