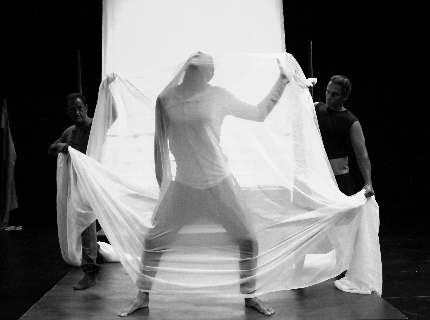

Jeremiah Musgrove waves a piece of fabric representing the sea as Serafin Falcon looks on in Tsunami / Photos by Monica Juarez

By Bill Hirschman

The nature of tragedy due to blind Fate, vengeful Nature, an inscrutable God or Gods is no revelation to the residents of Homestead or the Lower Ninth Ward or the Twin Towers neighborhoods.

What is endlessly worth examining and celebrating is how human beings cope and what that says about who we are, what we are capable of and some insightful guidance on how our souls can survive as well as our bodies.

These are among the themes of Tsunami, the world premiere by Miamians Nilo Cruz and Michiko Kitayama Skinner, a moving work of glorious theatricality that no other art form can duplicate.

This melding of movement-infused acting with superb designs of lights, shadow puppetry, sound, costumes, sets and projections grace the black box space at the South Miami-Dade Cultural Arts Center.

The script is drawn from on-site interviews conducted by the playwrights with 20 survivors one year after a 2011 earthquake and tsunami virtually erased the fishing village of Ozuchi in Japan, taking 1,300 lives. But unlike the similarly journalistic play, The Laramie Project, this one digs deeper and wider with a more universal aim.

Furthermore, it is far more stylistically staged with Cruz himself serving as director as he did on the similarly impressionistic Hurricane in 2014. Cruz has alloyed a half-dozen disciplines with a harmonious synergy in sync with his vision that result in tableaus of sight and sound that no one else could bring to his script.

Unforgettable is the image of large sheets of brown paper being wrapped tightly around standing motionless actors. The lasting impressions in the paper of their faces and bodies, looking a bit like Han Solo in Carbonite, are then stacked on shelves to represent bodies in a morgue.

Or a diaphanous blue silk drapery stretched across the stage, lit from behind, envelops victims still struggling before us under the lethal crush of water.

Tsunami charts the onset of the liquid wall, the survivors’ search for loved ones, the grief process, the political wrangling over how to protect themselves from future disasters and the slow quiet resolution as the people begin the never-to-be-completed healing process.

Among the issues the characters wrestle with is the seemingly randomness of it all. A collector of stories says, “It was a matter of life and death. Our lives were divided by thin lines; you either escaped by taking the right road or you were doomed by choosing the wrong one. Everybody came within a hair’s breadth of dying. It was a matter of luck! These are the stories that need to be heard.”

What is remarkable to Western sensibilities is the Japanese attitudes of restraint and sublimated emotion, other than the anxiety as they recall the storm itself. The triumph of the six-member cast portraying 14 characters is they create an imperfect stoicism that allows the audience to see the kaleidoscope of emotions flowing under the cauterized surface. While that pacific impassiveness may seem strange, these are storytellers relating events that occurred a year earlier; they have had time to develop mechanisms for bringing the pain under control.

It should be stressed that the verbiage is nearly absent the poetic imagery and magic realism that Cruz is famous for, such as his 2003 Pulitzer Prize-winning Anna in the Tropics, which bowed at New Theatre.

That’s because Kitayama Skinner, a Toyko-born University of Miami educator, and Cruz have drawn exclusively on the words of the people they interviewed. Aside from an occasional description of dreams, these are ordinary people speaking Kitayama Skinner’s faithful translation of their everyday speech. Still, these two playwrights have skillfully identified and arranged recollections that are inherently beautiful in reflecting the speakers’ purity.

The stories they tell are stunning as they try to reconcile living with the sense that the spirits of the dead are still present, and therefore, with the pain and loss that will never be banished, but which can be come to terms with.

There is the monk who feels compelled at a memorial service to give a Buddhist name to each of the 128 dead and missing from his temple “to show how they lived their lives.”

There is the inn owner who rejects the common practice of cleansing spirits from a site, citing an employee who still lives, eats and sleeps as if her spouse is still alive at home. The inn owner says, “I don’t think it should be about sending the spirits away. This is a place where the dead and the living have been living together for the whole past year. I know this might seem frightening for people from the outside, but for us, it is natural that we are here together. That’s why this hotel has become a waiting room for wandering souls.”

The production makes an asset out of the dearth of Asian-American actors in the region. By casting Anglos, Hispanics and an African-American who avoid Asian accents, the evening becomes instantly universal.

Not that the play is not suffused with Japanese culture and images; for instance, artful projections by Dinorah de Jesus Rodriguez depict real Japanese citizens played across Japanese calligraphy.

Then there is the soundscape by Erik T. Lawson. Along with the persistent sounds of now-gentled waves, the venue is awash in a mixture of new age music with clacking Japanese wood blocks, far-off bells and electric piano notes reminiscent of random raindrops falling after a storm has passed.

One section features an elderly man who teaches the Lion Dance and a middle-aged man who teaches the Tiger Dance screening young recruits because the storm has swept away so many experienced performers. They insist passing on their forefathers’ culture to a 2012 generation, a refusal to let the disaster destroy their history.

But it culminates into two life-sized large shadow puppets of dancers in the traditional Tiger and Lion costumes with colorful gleaming eyes battling behind a screen. Those and other puppets were created by Kitayama Skinner who also chose the different costumes and created the imagistic set featuring a few poles and flowing fabric arrayed in ingeniously communicative ways.

We’ve unfairly left until late the inestimable contribution of veteran designer Eric Fliss’ lighting. Because he is the managing director of the venue, he has little time for designing locally as well as conflict of interest issues as a county employee. That’s our loss. His work here — sometime delicately dappled, sometimes searchlight harsh – ranks as some of the loveliest, deftest and evocative lighting seen in the region in some time. But crucial is how well-integrated it is with Kitayama Skinner’s set design and Cruz’s staging. It enhances them to the point that the show would not work half as well with less skillful illumination.

The ensemble who perform a multitude of easily differentiated characters include Ben Prayz, UM educators Jennifer Burke and Maha McCain, Jeremiah Musgrove (memorable in GableStage’s Mothers and Sons), and Serafin Falcon and Andy Barbosa who played father and son in Hurricane.

Credit is also due Pablo Souki, production manager and technical director, and the seemingly impossible chore of coordinating a flash flood of sounds and lights by Amy Rauchwerger, production stage manager.

Tsunami is a production of the South Miami-Dade Cultural Arts Center (and therefore the county government’s cultural department) with support from the University of Miami Department of Theatre Arts and Arca Images, a small Miami-based troupe led by Artistic Director Cruz and Executive Production Director Alexa Kuve.

This is the kind of multi-disciplinary highly theatrical offering that is not seen often in Broward and rarely in Palm Beach County theaters. But it is worth a drive to this venue so far south to immerse yourself.

Tsunami plays through Oct. 3 at the South Miami-Dade Cultural Arts Center, 10950 SW 211 Street, Cutler Bay (Exit 11 on Turnpike). Performances 8:30 p.m. Friday-Saturday; 3:30 p.m. Saturday, 2:30 p.m. Sunday. Running time 1 hour 25 minutes with no intermission. Tickets $25 in advance, $30 at the door. Call (786) 573-5300 or visit SMDCAC.org.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design

Pingback: SURVIVALISTS BLOG | Humanity Struggles To Cope With Disaster in Tsunami | Florida …