Shelley Keelor, Elijah Word (in a wig) and Aaron Bower belt out a number in MNM Theater Company’s Closer Than Ever / Photos by Amy Pasquantonio

By Bill Hirschman

Let’s get this out of the way immediately: MNM Theatre Company’s filmed cyber-distributed pandemic production of the Maltby & Shire musical Closer Than Ever needs no excuses, no politely lowered expectations, no “Yeah, but.…”

Just as it would if produced live in an intimate venue, this effort mesmerizes and moves with the emotional power of performers acting this song cycle rather than performing them as if they were in a cabaret setting.

Don’t mistake this for one of those staged readings with everyone locked inside Brady Bunch-Hollywood Squares prison cells.

Indeed, the editing, lighting and staging banish any feeling of watching a static down-the-stairs-in-the-basement nightclub revue that this off-Broadway warhorse has undergone as a staple of regional theaters since 1989.

Marcie Gorman’s Boca Raton-based company, which does revues but is best known for large cast epics like Man of La Mancha, is somewhat breaking ground locally.

Under the direction of Jonathan Van Dyke, the production intermixes live performances, film techniques, scenic projections, deft editing, superimposed images of earlier performances and, of course, keeping everyone six feet away from each other — having only moments before doffed the masks they wore throughout rehearsals.

But rather than seem like an experiment of poorly fitting paradigms, Van Dyke, cinematographer-editor Cliff Burgess, musical director Eric Alsford and a small cadre smoothly integrate them most of the time. (To read a feature about the making of the show, click here.)

Crucial is that the quartet of experienced local musical theater hands – Aaron Bower, Johnbarry Green, Shelley Keelor and Elijah Word — never “deliver” a number. They don’t caress songs like a stylist, but with Van Dyke’s direction, they unearth the emotional truth in the words and play them like a conventional scene.

They inhabit the marrow and sinews of varied characters trying to navigate the emotionally perilous and profoundly confusing landscape of modern relationships as they sort their feelings in interior monologues of people gingerly reaching out to make a connection.

Some reviews over the years have sniped at the music and lyrics as conventional, and calculated (opinions with which this critic would aggressively differ). But these actors and their direction erase any such concerns because of the genuine emotion flowing out of them. Because of that, they seem less like performers; instead they are all-too-recognizable mirror reflections of our own angst, anxiety and hope.

Richard Maltby Jr. and David Shire, best known together for Baby and Big, wrote a two-act collection of songs with no dialogue or narrative. Instead, they seem to drop down on a crowded city intersection to spotlight middle-aged urbanites and let us hear their inner turmoil – sometimes with wry humor, sometimes with heart-breaking anguish, and ultimately with a bit of hope for the future. Their quandaries encompass parenthood, dating, aging, mid-life crisis, second marriages, cellulite, working couples and unrequited love.

Instinctively, you are aware of how they are arranged to keep the actors six feet apart. But like any theatrical contrivance, it doesn’t take too long to forget about it.

Much of this due to the direction and staging by Van Dyke, which rarely has anyone simply stand still and sing. People use body language and are in motion around the stage even when there is more than one person present. They enter and exit through four standalone doors that glide around as much as the actors. Green almost waltzes with a series of doors passing by him. Another time, the doors close in around an actress, trapping her.

But give extensive credit to the photography and especially the editing of Burgess under Van Dyke’s vision: It can lovingly embrace a performer’s face in anguish, or impose quick cuts among the quartet in group numbers, or cross-fade from one singer to the other.

While some numbers were photographed more than once for various reasons, often multiple cameras shot the same iteration of the same performance. So a full-body shot of a performer singing might cross-fade to a close-up obviously filmed at the same time. The result is a heightened sense of the kind of theatrical intimacy you subconsciously perceive in a live performance as you sit inside a theater.

Credit, too, for providing an endless variety of sense of place in what is essentially a shallow empty black box goes to Clifford Spurlock for ever-morphing lighting that reflects the interior emotional tumult.

Most of the time, the impression is the capture of a live performance, but occasionally the company plays with electronic possibilities. The four doors on stage can turn around to provide a screen for a few painted projections such as the view of NYC from across the river at night.

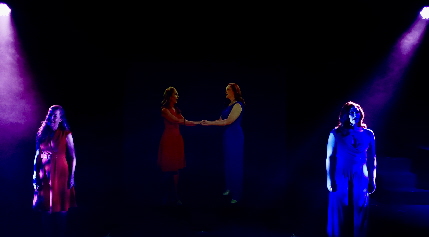

But – and this has to be seen to be understood completely — the performers were also filmed separately earlier than the primary performance. This meant that they can perform a group number seemingly side-by-side by having superimposed projections of them lined up side-by-side. Or they can be singing “live” to an adjacent projection of themselves singing with them. At one point, two of these projections seem to be shaking hands. The use of those projections are obvious when they’re done; they almost seem like ghosts, but no matter.

These techniques heighten the experience in that these are personal reveries whose impact would be hampered in a traditional venue (although it has been done that way hundreds of times) and would be lost in a large venue like the Rinker Playhouse at the Kravis Center where MNM has been based.

Local companies have been experimenting with some of these techniques even before the pandemic, such as Theatre Lab’s use of videoed scenes interspersed with live scenes last December in Everything Is Super Great. But this is another level.

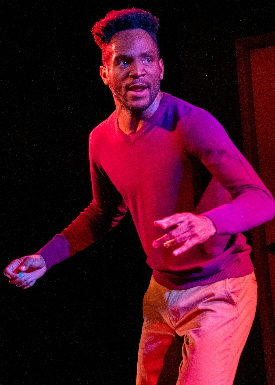

Elijah Word

As for the actors: While he is no more outstanding than the others, Word’s work here is a revelation of a talent and skill that has grown year after year. Tall and lithe like the dancer he is, he won a Carbonell Award for his portrayal of the flamboyant James Thunder Early in Broward Stage Door’s Dreamgirls in 2017. None of this prepares you for his nuanced evocation of quiet deep emotions. He can portray a love-obsessed stalker in “What Am I Doin’ ” or sinuously dance to Emily Tarallo’s choreography as a sexy commentary to Keelor’s jazz-inflected “Back on Base.”

Bower, often wearing a long red wig, can be heart-breaking one moment leaning against an invisible proscenium in a spotlight singing about a life stuck in a rut in “Patterns” or a lab-coated naturalist unleashing a hilarious venting against men compared to the animals she studies.

The vivacious Keelor, adept at mining the depths of a ballad, can be a hoot as Miss Byrd, a seemingly staid office drone with a surprisingly active sex life. She and Green are a stitch when it turns out that he no longer wants to be lovers but offers to be friends.

Green, who looks like the next door neighbor who forgets to return your lawn mower, has a bent for comic portrayals, but he will shatter the reserve of any late middle-age male as he describes that his character’s love of music is the bond he shares with his aging crippled father in “If I Sing.”

The masterful Alsford – who plays piano along with Martha Spangler’s bass – once again has melded and molded the voices to create a soundscape of humor and heart.

The evening is an hour and 40 minutes include a one-minute intermission in which you can just hit pause to visit the little boy’s room and the popcorn popper. The only thing missing is a program (perhaps provided in the future online with the link).

A word of advice: If possible, don’t watch it on a laptop or tablet or phone. Run a HDMI cable from the computer to your television.

Look, it is impossible to see any Theater online and not ache to see it live inside a theater with the actors interacting with you as well as their colleagues, but this will do for the time being. My bet is when it’s over, you will instinctively applaud.

Closer Than Ever runs through Dec. 31 from MNM Theatre Company. On-line links e-mailed upon purchase are good for multiple viewings for 48 hours after the first sign-on. Running time 1 hour 40 minutes with one intermission. Tickets, $20. For tickets, go to https://www.mnmtheatre.org/.

Shelley Keelor and Aaron Bower serenade themselves shaking hands thanks to technology in MNM’s Closer Than Ever

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design