By John Thomason

By John Thomason

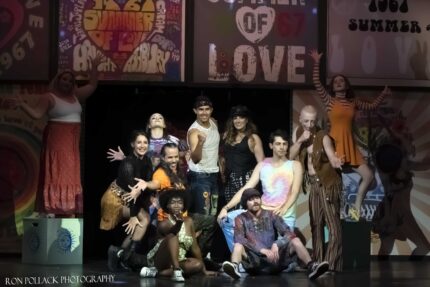

Against a backdrop of posters promoting love, flower power and Woodstock, the title character emerges from behind the curtain, hunky and shirtless, in underwear decorated with peace signs. He dresses, silently and unhurried, his fraying jeans festooned with patches matching the Summer of Love motif. Once clothed, he notices a skateboard nearby and rides it to across the stage to a boombox, where he inserts a cassette and presses PLAY, cueing Stephen Schwartz’s score, and thus beginning Pembroke Pines Theatre of the Performing Arts’ re-imagined rendition of Pippin.

The musical, from Schwartz and book writer Roger O. Hirson with contributions from original choreographer Bob Fosse, is technically set during the Holy Roman Empire, but its cheeky and Brechtian structure have long welcomed modern interpretations. Diane Paulus’ 2013 Broadway revival famously set Pippin’s journey of self-discovery against the acrobatic bustle of a traveling circus.

In Pembroke Pines, under the debut direction of Richard Weinstock, the theme is at once vivid and nebulous. The costumes (also designed by Weinstock) match the décor’s tie-dyed, psychedelic and DIY vibe. But putting aside the temporal oddity of the portable cassette player—that would emerge a generation or so after Woodstock—the ‘60s-era set dressing is just that, seldom bearing a relation to the text. Because the direction and choreography don’t provide a consistent sense of time and place, you might have the disconcerted feeling that you’re watching a Pippin production on a recycled Hair set.

The story chronicles the fabled Frankish prince of the title (Stefano Galeb), eldest son of the marauding emperor Charlemagne (Lito Becerra), as he searches for meaning in life’s disparate pursuits. Pippin is stuck in a state of malaise, hoping to fill the emptiness in his soul with education, with war, with sex, with religion, with political revolution and ultimately with a life of bucolic simplicity.

His odyssey is presented as a ramshackle show-within-a-show of sorts, supported by an industrious chorus and narrated and overseen by a Leading Player (Christina Carlucci), whose vision for the production gradually loses its tether, culminating in one of musical theatre’s most radically deconstructed endings.

There is plenty of formidable talent on the PPTOPA stage. Galeb captures Pippin’s searching, enthusiastic naivety, and Becerra impresses with the Gilbert-and-Sullivan-style phrasing of “War is a Science.” Lory Reyes visibly has a great time as Pippin’s Grandma Berthe, who in this production smokes a bong, all the better to deliver hippie wisdom to her grandson. (This is one of the few times the ‘60s motif gels.)

Anna Cappelli is a buoyant and charming Catherine, the widowed homesteader who finally provides the restive Pippin with a sense of belonging. And Carlucci makes for an accomplished and shrewd Leading Player, even if her black-and-white costuming looks more Cabaret than Pippin, especially on “Simple Joys,” a tonally jarring, canes-and-top-hat homage to Fosse’s jazz-handed signature.

But the issues with this Pippin are more fundamental than a curious design element, the occasional microphone malfunction (there were several on opening night), a flubbed line or a performance that leaves one wanting more. By dint of budget or vision or both, this scaled-back interpretation simply lacks spectacle, which has always been one of the musical’s necessary elements. A sense of withholding permeates Del Marrero’s choreography, with its basic steps and absence of flash; the movement looks easy for dancers of any amount of seasoning. And in too many numbers, there is neither choreography nor background action to flesh out the scene, and the pace drags.

This Pippin would have benefited from more maturity on and off the stage. The cast slants so young, with actors of roughly the same age playing characters separated by generations, that some of its jokes fail to jibe with reality (The Leading Player’s sardonic quip about removing the “young” designation from “young widow” Catherine doesn’t work because, of course, Cappelli is young.) Nor do the actors have the gift of a live orchestra with whom to synergize. Playing off tracks at a fairly low volume, Schwartz’s jaunty pop-rock score feels flat, and seldom rouses.

As we’ve discussed previously regarding South Florida regional theater, the paradigm of reviewing a show on its opening weekend can do no favors to a hardscrabble production that, with almost no preview performances in the rearview, can take a while to find its collective footing. Even over the course of Pippin’s opening night, the second act proved to be livelier and more impactful than the first. The gags landed better, and the movement was more firmly in the pocket.

Moreover, the show’s stripped-down—in more ways than one—climax remains a radical and subversive comment on the artifice of theatre. The problem is, it needs a sense of preceding magic to fully work as a point of contrast. This Pippin doesn’t soar high enough, but at least it sticks the landing.

Pippin plays through April 30 at Pembroke Pines Theatre of the Performing Arts, 17195 Sheridan St., Pembroke Pines. Performances are 8 p.m. Fridays, 2 and 8 p.m. Saturdays and 2 p.m. Sundays. Tickets $25-$35. Call (954) 437-4884 or visit pptopa.com.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design