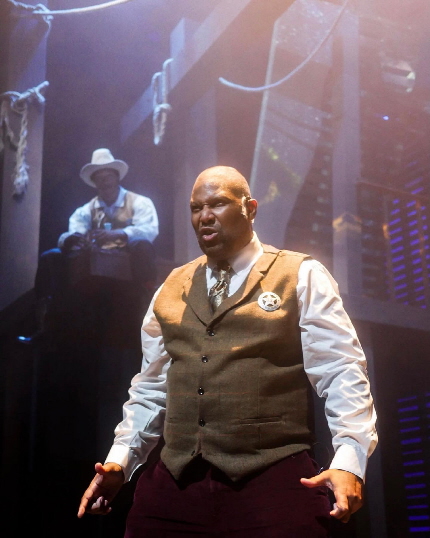

Playwright-director Layon Gray also stars in M Ensemble’s Cowboy (Photos by Christa Ingraham)

By John Thomason

It’s a classic trope of the American western: A lawman and a random assembly of strangers are forced, by Mother Nature or custom or providence, to share tight quarters for a while, until buried revelations finally surface amid smoking guns.

In Howard Hawks’ archetypal Rio Bravo, the setting was a jail. In playwright, director and actor Layon Gray’s latest labor of blood, sweat and tears, Cowboy, it’s a dilapidated saloon “somewhere in Indian Territory.” But it’s presented, in its regional premiere at M Ensemble, as a place of myth as much as wood and sawdust—a misty waystation on the road to absolution, where time-honored themes of western literature are both satisfied and critiqued.

The law enforcement officer, in this case, is Bass Reeves (Gray), an imposing but unruffled and inscrutable sort who holds his cards close to his vest—metaphorically and, we’ll soon learn, literally. He enters the Wet Whistle Saloon with his partner Grant Johnson (Jaerez Ozolin) by his side, their intentions undetermined. Moments later, two drifters saunter in, their destination Mexico: Levi Colton (Reginald Wilson), his inherent shadiness telegraphed, perhaps a bit too much, by his battered black Stetson and overcoat, and his tagalong brother Gus (Charles Reuben Kornegay), who suffers from a mental disability and seems incapable of self-determination. A monster storm looms just outside the tavern’s rickety frame, and it will keep everyone there for the next 80 to 90 real-time minutes.

Bass Reeves was a real person, a master gunslinger and the first Black deputy U.S. marshal west of the Mississippi River, who notched some 3,000 arrests and killed 14 criminals reportedly in self-defense. But he was an enslaved man first. Permeating the plot of Cowboy is the legacy of America’s original sin. All the characters above a certain age survived the horrors of slavery, and their backstories of shared trauma link them even when they appear on opposite sides of the present conflict.

Gray is a fine writer—as in much Tennessee Williams, there’s a regional poetry in the characters’ communication—but he’s an even better director. The mesmerizing theatricality he brought to the staging of M Ensemble’s triumphant Kings of Harlem in 2017 is present here as well. Gray sees dance everywhere: Action scenes play out as pistol ballets, as elegant in their blocking as they are chaotic in their premise. Characters’ backstories are punctuated by lively percussion, as spurred boots stomp the floorboards and fists rap on tables in ritualistic harmony. When Reeves shares a story that expresses his gun-fighting prowess, Gray offers the tale as any master storyteller would, functioning as mime and monologist, painting vivid pictures in our minds.

In this rollicking environment, moments of musicality, from shared slave songs to an eruptive rendition of “Cotton-Eyed Joe,” spring from the characters’ knockered conviviality—and the actors’ infectious chemistry. Gray directs the latter sequence with the manic energy of a farce, which makes its abrupt transition from jubilation to agony all the more powerful.

The cast feels entirely in tune with the play’s florid expressionism, from Wilson’s shifty Levi to Kornegay’s mentally impaired Gus, whose hidden duality is one of Cowboy’s most effective revelations. Isaac Beverly contributes jittery comic relief as the saloon’s bartender, providing welcome levity when it’s most needed.

Mitchell Ost is the back-of-the-house superstar on triple duty. His two-story set is a mini-marvel of collapsible construction—just wait until that promised storm finally lands—while providing a backdrop for his own projections, from train cars to rain showers. His lighting design is defined by its divine beams bisecting actors’ faces, a potent symbol of their increasing dichotomies.

In short, Cowboy is everything audiences expect of a rousing western, but it’s also an inherent indictment. It is not of little significance that the play is presented with entirely Black actors in a genre that has only recently begun to welcome melanin in its ensembles. We’re in the 2020s, but still try to find a production of Oklahoma! that isn’t “traditionally” cast, as HBO’s Watchmen so starkly reminded us.

For Gray, this is not simply a correction, and it’s certainly not a novelty. Underlying the whiskey shots, the piano playing and the gunfights associated with western lore is a tortured account of the way slavery tore apart families, ruptured relationships, even forced some to self-mutilate for the own protection. The terrible legacy of Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act is acknowledged as well through the character of Grant Johnson, who is half indigenous American. Even the etymology of the play’s title—“cow boy,” two words—ends up referencing the degradations and depredations of plantation life.

An epilogue spoken ostensibly by Bass Reeves but more explicitly by Gray unnecessarily underlines these points from the perch of hindsight; this painful subtext is present enough throughout the action. It’s even there in the perennial mist that blankets the set. This approach creates at atmospheric ambiance, but it’s doubly appropriate for a play that resides in the murk of history—where the creaky paradigms of cowboys and Indians, heroes and villains, white hats and black hats, disappear in the fog of a century-long institutional evil.

Cowboy at M Ensemble runs through June 27 at the Sandrell Rivers Theater, 6103 N.W. Seventh Ave., Miami. In this specially priced production, tickets purchased online cost only $16. Face masks are required inside the building. Call (305) 200-5043 or visit themensemble.com.

To read a feature about the play, the playwright and the production, click here.

Mitchell Ost’s evocative set for Cowboy

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design

One Response to Slavery & Mythos of the West Haunt M Ensemble’s Cowboy