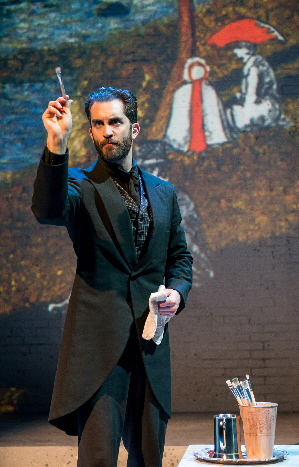

The second act opening tableau of Zoetic Stage’s Sunday in the Park With George / Photos by Justin Namon

By Bill Hirschman

A wave of sheer glory lifts the audience into a firmament of validation, redemption and pure beauty in the last ten minutes of Zoetic Stage’s production of the Stephen Sondheim-James Lapine masterpiece Sunday in the Park with George.

That alone makes this production a don’t-miss evening of theater. While niggling flaws do mar perfection, they are a tiny price to pay to experience one of the best evenings of musical theater that this region has been privileged to witness.

Sunday is arguably theater’s most incisive exploration of artistic creation and the tumultuous inner struggle of those who commit their very being to that pursuit. Even for those who simply have the urge to create – regardless of their actual talent, skill or follow through – Sunday is a celebratory cathartic cry of the heart that resonates in the depths of their soul.

If you’re a rabid Sondhead like this critic, you have treasured other productions, and indeed, this work creates a precise structure that must be worked within. But most of Zoetic’s work here sculpted by director Stuart Meltzer and musical director Eric Alsford is so imaginatively conceived and skillfully effected that it marks its own iteration. From inventive projections to a flawless orchestra to lead performances awash in vitality and intensity, Zoetic’s Sunday exudes its own specific pungency and power.

For deprived souls unfamiliar with the work, Sunday fictionally depicts French post-impressionist Georges Seurat in the 1880s as he struggles two years to paint the ground-breaking “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.” Although revolutionary in several aesthetic ways, it was most obviously remarkable for scientifically combining dots of color to magically create a different hue when patrons viewed it from a distance.

Georges (Cooper Grodin) is obsessed with realizing his vision. The price he pays is distancing himself from people — not just society with its restrictive norms, but a failure to give enough of himself emotionally to his true love, the model Dot (Kimberly Doreen Burns). While they have a deep passion, his inability to devote a portion of his life solely to Dot causes her to marry a baker who takes her to America with Georges’ love child. Georges then instills order to the chaos of his personal life by arranging and revising his painted recreation of a disparate array of everyday Parisians enjoying a suburban park.

The second act occurs a century later when his great-grandson George, who creates avant-garde light-emitting installations, is struggling with a similar inability to connect fully with life, precisely at a juncture when he is feeling artistically adrift. With the advice of his grandmother (Georges’ love child) and the ghost of Dot, the modern-day George must work his way through his issues to find an emotionally healthy, not balance, but fusion.

A plot description does an injustice to the piece, which won the 1985 Pulitzer Prize, Tonys and a slew of other awards. Sondheim’s complex music and lyrics, and Lapine’s script are incredibly challenging both for thespians and for patrons more receptive to The Sound of Music or My Fair Lady.

Zoetic brings three-dimensional life to that interior struggle between the costly choice of living for and inside your art – and conversely living a full life outside it, and then realizing that both are necessary to be a complete human being.

Any filmmaker or playwright can tell you that among the hardest things to satisfyingly depict is the act of creation. Zoetic has succeeded – in part because of Grodin’s deft performance, but also because Meltzer has led a team that has made that process clearly visual.

Specifically, Michael McClain’s set begins as empty beige stone and white-washed brick walls. Angelina Esposito’s period costumes are white, taupe and ecru except for Georges’ jet black garb. Rebecca Montero’s lighting seems as brightEric as that of a studio.

Then Greg Duffy’s animated projections limn lines of charcoal appearing on the back wall one at a time, creating what is in Georges’ sketchbook. Those sketches will provide various backgrounds such as Georges’ studio. Eventually, it illustrates the empty park in a monochrome filling the back wall. As the show progresses, the image changes, is revised before our eyes as Georges revises his sketches, characters appear, color begins to enter the painting, the lighting scheme gains tints, individual pieces of clothing worn by the actors gain color one garment at a time.

Therefore, the glorious cap to the first act is how these hard-wrought pieces of Georges’ imagination coalesce into the familiar masterpiece. That sense of coalescing is echoed in a more metaphorical and emotion sense in the final scenes of the second act as the halves of George’s life finally meld.

Zoetic has hired a superlative cast. Grodin, who played the national tour as the Phantom of the Opera, attacks his words with a fervor that speaks to Georges’ internal agony. His Georges knows full well that he is chronicling a world that he does not feel a part of and he is painfully aware that this distance is exacting a cost in the sole relationship he prizes with Dot. Grodin is a warmer more genial Georges than how some other actors have played him, but he embraces Georges’ neurotic defense mechanism of rudely stiff-arming people when they want more than he can give,

The tall, slender Grodin, who looks a bit like Joseph Fiennes in Shakespeare in Love, exudes Georges’ intelligence, angst and an ability to forcibly contain himself in public like a taciturn curmudgeon, and then in private, to be torn by anguish or playfully revel in his imagination imitating dogs in the park. His smoldering eyes blaze with discontent and passion. It’s a foregone conclusion that he sings expressively whether the notes sink to the basement or reach the stratosphere.

The tall, slender Grodin, who looks a bit like Joseph Fiennes in Shakespeare in Love, exudes Georges’ intelligence, angst and an ability to forcibly contain himself in public like a taciturn curmudgeon, and then in private, to be torn by anguish or playfully revel in his imagination imitating dogs in the park. His smoldering eyes blaze with discontent and passion. It’s a foregone conclusion that he sings expressively whether the notes sink to the basement or reach the stratosphere.

Burns, who has credits in New York and regional theaters, is every iota as effective. While she has a clarion belt equal to her predecessors in the part, her drolly impish expressions, inner glow and vitality are her own. The petite soprano creates a warm, witty and vibrant Dot who is an everyday person from the streets and the shops who wants to better herself by learning to read and find a way into Georges’ world. As a symbol of the appealing facets of the outside world, Burns creates a Dot who offers Georges a lifeline.

Both actors under Meltzer’s guidance create human beings consumed with palpable yearning for each other but who face obstacles they cannot resolve.

The 17-member cast, which includes local veterans and polished collegiate actors, is solid. They include Carol Caselle as Georges’ mother; Margot Moreland as her nurse; Chaz Mena as the oily servant; Stephen G. Anthony as the establishment painter; Anna Lise Jensen (Clara in Zoetic’s Passion) as his wife; Michael Freshko as the boatman (a murderously difficult role to sing); plus Jayne Ng, Michael Scott Ross, Lucia Fernandez de los Muros, Kelly Gabrielle Murphy, Jeni Hacker (Fosca in Passion), Jonah Robinson, Shannon Booth, Bennett Leeds and Rick Hvizdak. And, of course, all of them play different roles in the second act.

The coordinated elements of lighting, set design and especially Duffy’s imagistic projections overseen by technical director B. J. Duncan and executed nightly by stage managers Amy Rauchwerger and Cassandra Kris cannot be overpraised in creating the evolving environment. The sound by Dan Mayer is superb from the subtle atmospheric noises in the park to the balance of voices with a sharp clear bright sound of the orchestra.

Alsford molded pungent acting performances with the singers, and led an offstage five-piece band who sound like twice that number, including Nicole Patrick, percussion; Rick Kissinger, reeds; Elena Alamilla, cello and Casey Maltese, French horn.

In all three of Zoetic’s Sondheim productions, including Assassins and Passion, Meltzer’s love and understanding of his works is blindingly evident. While much of the staging of Sunday is dictated by the action, Meltzer puts his own stamp on the proceedings where possible such as the “Art Isn’t Easy” scene in which sycophants and critics at a cocktail party devolve into robotic movements. But his real skill is how he elicits as fully-realized acting in musicals from his cast as he does in his straight dramas.

To be fair, Sunday is not a perfect piece either in raw material or execution. Lapine’s script bogs down in the first act as he feels compelled to illustrate the communal intersecting backstories of every single character in the painting. George’s Act 2 electronic art is not very impressive here. Finally, a Granny Clampett grey wig and glasses is not enough to convince anyone that the smooth-faced strong-voiced Burns is George’s 98-year-old grandmother in the second act. But, hey, it’s theater; suspend your disbelief.

All is forgiven in the closing scenes of both acts as the elements, visual and emotional, coalesce and soar into a shimmering work of art.

Sunday in the Park with George from Zoetic Stage as part of the Theater Up Close series performs through Feb. 12 in the Carnival Studio Theater at the Arsht Center’s Ziff Ballet Opera House, 1300 Biscayne Boulevard, Miami. Performances are at 7:30 p.m. Wednesday-Saturday, 4 p.m. Sunday. Tickets are $50-$55. Running time is 2 hours 40 minutes with one intermission. (305) 949-6722 or www.arshtcenter.org.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design