By Bill Hirschman

By Bill Hirschman

Hamilton, which explodes with power, vitality and imagination in the Kravis Center through Feb. 16, is not the Second Coming as many overheated observers would have you believe. But this tour demonstrates why this musical epic is a watershed work that may well transmute mainstream theater for a decade to come.

The production, which moves to the Arsht on the 18th, is dazzling from the hip-hop score to the sight of a multi-cultural cast in frock coats and tricorns standing in for the Founding Fathers previously depicted as white Anglo-Saxons. Creator Lin-Manuel Miranda’s genius – besides for incredible lyrics – is convincingly linking the 18th Century and the 21st with deafening resonance.

When Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson face off in a debate about, believe it or not, the National Bank, it resembles nothing so much as dueling rappers in a def jam trying to cut each other like jazz masters. When a fatuous King George paternalistically scolds the colonists, he resembles more than a few disconnected politicians of today.

The clear-eyed truth is that nothing in this “groundbreaking” musical is new. Virtually everything has been experimented with and implemented before. Hamilton’s indisputable triumph is the superlative way all those elements have been seamlessly, precisely and expertly melded into an entertaining, intriguing whole and on a scale rarely seen in modern American theater.

The result is that Hamilton seems revolutionary, especially for people who do not often go to theater or whose exposure is limited to traditional mainstream tropes or young people who dismiss it as an out-of-touch passé source of entertainment. Indeed, the advance hype has fueled expectations nearly impossible to fulfill – but it comes darn close.

Suffusing everything and partly accounting for its appeal to pre-retirement-age audiences is the overwhelming sense of yearning that so commands the soul of everyone from adolescents to thirty-somethings. The universal hunger is to find a place in the world by finding strengths, transforming them into achievements and thereby discovering a sense of self-worth – with the perception that a mortality clock is always ticking even for the young,

Further, contemporary audiences will relate to aspects such as frustration battling the slow-moving establishment, the fate of the country decided in exclusionary backroom deals, a perpetual sense of never being satisfied, the sense of living in a time of revolution (that should resonate with the Millennials’ parents), inviolable ideals deteriorating in the face of pragmatism, the contribution of immigrants to the young nation, and the sense that the world has been turned inside out — a source of both fear and opportunity. Alternately very funny and profoundly moving, it delivers a seminar-full of insights about the American character — where we came from and who we are today.

Secretly, Hamilton is a good ’ol American musical theater in construction, sensibility and its highly polished precise execution. Miranda comes from, reflects and incorporates a wide variety of influences including growing up listening to original cast albums as well as venerating Stephen Sondheim.

So, now the asterisks: While many lyrics lapse into the incomprehensible, the actors’ enunciation of the brilliant but dense verbiage is far more clear in this Angelica tour than the mish-mash audible when a different tour came through Broward a year ago. (Once again, no one understands more than five or six words that Lafayette sung during the entire first act.) But folks, we’ve told you in previous reviews, every interview, every advance feature, we keep warning patrons to listen to the score and read the lyrics ahead of time – even though Sondheim has always advised that the best lyrics are understood on the very first hearing.

One reason that’s crucial is that boxcars of necessary exposition fly past like a freight train. Years are conflated into a few sentences. Relationships are introduced in a few words and then they’re gone. For an audience alleged to have generation-wide ADHD, this is not The Lion King that allows you to watch passively. This requires complete involvement and rapt attention if you are not to miss the content and the artistry of the verbiage rushing past. This is storytelling on steroids.

The vibrating music is infectious and the lyrics scintillate in a celebration of art and intelligence that embraces tongue twisting displays of verbal pyrotechnics and deeply felt poesy.

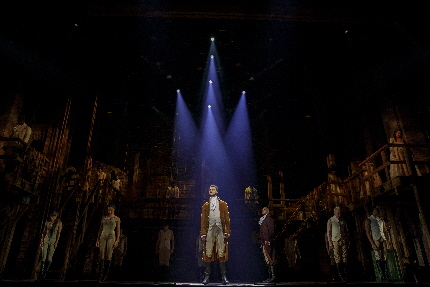

Director Thomas Kail’s staging is melded into Andy Blankenbuehler’s kinetic choreography, which is the ever-present terpsichorean equivalent of the sung-through score. Together, their visuals ensure that an enraptured audience can plug into the energy and understand the vibe even when they can’t understand the words.

Civilians might not notice, but one of the most outstanding contributions came from Tony-winner Howell Binkley whose atmospheric lighting creates scores of emotional and physical environments. And the production stage manager deserves twice her salary for overseeing the lightning fast cues along with her other duties. The sound of the kick-butt band pulses with an overwhelming bass and percussion slamming the auditorium, commanded by music director Patrick Fanning.

For the 14 people living in a convent in Lower Slobovia in the Upper Balkans, Hamilton is the 2015 sung-through retelling of the life of the eponymous historical figure. Miranda spent six years working on and off with a cadre including In The Heights cohorts Kail, Blankenbuehler, and musical director/orchestrator Alex Lacamoire (a former New World School of the Arts student) to retell the arc described in Ron Chernow’s 2004 book.

Miranda saw resonances between Hamilton’s life and the creation of this country with those of today’s multi-cultural factious society of mostly young ambitious contemporary generations. They used the musical genres of hip-hop, rap, jazz, blues, rock, an echo of boogie woogie and a bit of Broadway, and then cast all the parts other than King George with minorities. Miranda took the lead part and the show cemented the stardom of Leslie Odom Jr. as the nemesis Aaron Burr.

Specifically, this would seem an intentionally disconnected clash of a mid-20th Century art form and a 21st Century score, of an allegedly only-today-matters generation and a multi-faceted history lesson rooted two centuries earlier, of a diverse cast with ponytails and Afros deftly performing century-old theatrical skills associated with Anglos, WASPs and Jews. But the exact opposite is true. The genius of the piece is how it melds those facets — not mashes them. It finds genuine reverberations that make aficionados on all sides not only see the relevance of each, but revel in that surprisingly shared experience.

The resulting work electrified audiences across ethnicities, ages and income levels. As word of mouth turned into a tsunami, the original cast recording reached far more people who geographically or economically could not see the show itself. Some of the lyrics entered the catchphrase lexicon such as “I’m not throwing away my shot” and “the room where it happens.”

The stage story – a mixture of fact and fiction — tracks this orphaned immigrant from the West Indies as he arrives in New York in 1776 to become a fiery speaker and lawyer, and is immediately caught up in the rebellion, then becomes an aide de camp to Washington during the war, marries one of the Schuyler sisters while fighting feelings for another. He becomes embroiled in the politics of the young country with changing fortunes along with new administrations. Along the way, he co-authors The Federalist Papers that served as a basis for the Constitution and serves as Washington’s Secretary of the Treasury. That leads to an ongoing philosophical fight with Thomas Jefferson. He runs afoul of former friend Burr, resulting in the duel that took his life at age 47 (or 49).

The political turmoil and issues surrounding his economic policies and the like are difficult to follow, but the energy of the cast and the musical’s raw material make mesmerized audiences simply not care about his vision whether states should erase the national debt.

Playing directly against the contemporary syntax are the physical facets. Costumes are period perfect ruffled shirts, bright waistcoats, knee-high breeches, swirling dresses and thigh-high boots. The setting is a complex of catwalks, timbers, deteriorating brick walls and block-and-tackle contraptions like the naked backstage of an 18th Century theater or a warehouse at the New York docks of the same period.

Most of the time, the evening is an awe-inspiring and frightening specter of a huge boulder careening down a hill right at you. Throughout, there is the sense, just as Hamilton feels, that the mortality clock is always ticking. This being my third time, I will admit that the second act is not as enthralling as the first act and the entire evening does feel like it goes on just a hair too long.

The cast members, from the leads down to the ever-present dance ensemble, are fluidly smooth and knife-edge confident; some have been with the show a year, some have been in other roles in other companies. This pays off in the multi-dimensions delivered by Edred Utomi as Hamilton, Josh Tower as Burr, Stephanie Umoh as Angelica, Zoe Jensen as Eliza, Paul Oakley Stovall as Washington, and Peter Matthew Smith as a showstopping King George.

Theatergoers may argue whether Hamilton is all it’s been hyped to be, but from the defiant, fierce and joyful opening phrases about a bastard immigrant destined to become “a hero and a scholar,” Hamilton proves itself an electrifying game changer in the world of musical theater – and then continues to do it for another 2 hours and 50 minutes.

Hamilton through Feb. 16 at the Kravis Center for the Performing Arts, 701 Okeechobee Boulevard, West Palm Beach. Running time: 2 hours 50 minutes including one intermission. Performances are 8 p.m. Wednesday-Saturday; 2 p.m. Saturday and Sunday. Tickets (bought from the Kravis Center as opposed to scalpers) are $67.50– $361. Available tickets left are in the single digits. For more information, call (561) 832-7469 or visit kravis.org.

Then plays Feb. 18-March 15 at the Adrienne Arsht Center for the Performing Arts, 1300 Biscayne Blvd., Miami. Performances 8 p.m. Tuesday-Saturday; 1 p.m. and 7 p.m. Sunday. Tickets $79-$449

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design