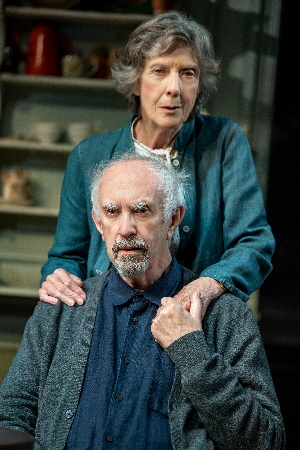

Ian Barford and Caroline Neff in the Steppenwolf Theatre Company production of Tracy Letts’ “Linda Vista.” Directed by Dexter Bullard, “Linda Vista” will play through February 17 at Center Theatre Group/Mark Taper Forum. For tickets and information, please visit CenterTheatreGroup.org or call (213) 628-2772. Media Contact: CTGMedia@CTGLA.org / (213) 972-7376. Photo by Craig Schwartz.

We’re back from our trip to New York to scout out productions you might want to see (or not), shows that might tour South Florida and scripts that might be worth reviving in our regional theaters. We will post reviews over the next week or so between local productions.

By Bill Hirschman

Some of the shows we saw on our recent trip to New York — Tracy Letts’ Linda Vista and The Height of the Storm — were limited runs and closed before many of our readers could get there. But they pointed out opportunities for works we’d love to see attempted on local stages in Florida and around the country..

Linda Vista

Tracy Lett’s newest alchemic work melding of comedy and drama is the one most likely to have a healthy afterlife — nearly guaranteed to anger some patrons and entertain others, but make both think.

The transfer from Letts’s home at Steppenwolf to the Second Stage Theater with key actors in tow depicts a 50-year-old obnoxious, insecure and uber-witty jerk whose marriage has disintegrated and proceeds over two acts to screw up two more relationships.

Dick Wheeler looks and sounds more like a furloughed halfback drunk at the bowling alley than the newspaper photojournalist he once was. As he moves boxes into a San Diego apartment with his buddy Paul, he unreels a steady stream of witty one-liners with a kind of over the hill macho plaid shirt charm. His F bomb-laced boys’ banter includes comparing how hot Ali MacGraw was in their youth. The cleverly articulate and acidic Wheeler holds forth on what an idiot Donald Trump is. He rants about mediocrity but certainly sees himself in that category.

He is quick with a quip that he may or may not actually believe, such as when talking about a woman’s right to choose when she gets pregnant. He snaps out, “I think a woman should be able to terminate until it can make a cogent argument in its defense.”

But Wheeler clearly is feeling his age and Paul’s pressure for Wheeler to reenter the relationship market is greeted with one of his easily unloaded bon mots: “I don’t want someone too young to remember New Coke.”

As we see him in his job as a camera repair man, the audience can see that under the intentionally distancing curmudgeon-ness, there is profound self-loathing, disillusionment and desperation as his life has been set adrift. Wheeler is both a fascinating, intriguing and off-putting character who seems incapable of having a meaningful relationship because he sabotages everything around him.

During the play, he has a relationship – one with surprising potential – with a middle-aged woman who seems the exact brand of New Age nut he savages (she’s a life coach with a master’s degree in Happiness), but whose positive attitude, growing affection and compassion win him over. For a while. But it should be no surprise that he self-destructs the bonding out of fear. Then he improbably takes up with 20-year old Vietnamese-American self-described “rockabilly chick.” Obviously, this is doomed as well. His treatment of these woman is guaranteed to piss off many people in the audience.

Over the evening, Wheeler may (or may not) begin to have glimmers of self-knowledge and even the stirrings of long-dead hope for any kind of future.

A key in Dexter Bullard’s well-directed production was the central performance of Ian Barford who labored to keep much audience loyalty as possible while Wheeler knowingly and intentionally shot himself in both feet and uttered sexist, paternalistic and misogynistic witticisms. When this is done in regional theaters, casting will be the key challenge. And artistic directors should know that two characters are nude for extensive periods and the language is R-rated.

Letts’ August: Osage County also was built around an objectionable fulcrum character, but here he has some well-hidden empathy for the modern American middle-aged male trying to navigate an ever-morphing world.

The Height of The Storm

Who to believe and what to believe, even what is real and what is imagined are the core questions depicted in this moving troubling drama that was performed at the Manhattan Theatre Club last month — the second time that French novelist and playwright Florian Zeller has had a New York City production merging his themes of an unreliable narrator and encroaching dementia.

Like his similarly brilliant The Father with Frank Langella in 2016, the audience is never quite sure what is real, what is imagined, what is accurately perceived, what is misperceived, is everyone in the same room, at the same time period – and in this play who is alive, who is dead, even who is telling the story.

Zeller, whose script was translated once again by Christopher Hampton (Les Liaisons Dangereuses and the works of Yasmina Reza) makes no attempt at all to answer the questions. Rather he luxuriates in the depiction of a world in which the characters and the audience will never know the answers.

This production directed by Jonathan Kent boasted the work of three superb craftsmen in the theater: Jonathan Pryce and Eileen Atkins deliver master classes in acting with breathtakingly skilled and nuanced performances. The third is lighting designer Hugh Vanstone whose work is some of the best illumination we’ve seen in any drama in years – not simply the slanting shafts of light coming through a kitchen window, but the changes of time and place communicated solely through the oh so subtle ebb and flow of intensity and color, helping send a subconscious message to the audience that the point of view (or reality) has changed, plus directing the audience to where the director wants them to be looking.

This production directed by Jonathan Kent boasted the work of three superb craftsmen in the theater: Jonathan Pryce and Eileen Atkins deliver master classes in acting with breathtakingly skilled and nuanced performances. The third is lighting designer Hugh Vanstone whose work is some of the best illumination we’ve seen in any drama in years – not simply the slanting shafts of light coming through a kitchen window, but the changes of time and place communicated solely through the oh so subtle ebb and flow of intensity and color, helping send a subconscious message to the audience that the point of view (or reality) has changed, plus directing the audience to where the director wants them to be looking.

The premise, at least it seems to be at first, is that a middle-aged woman has come to watch over her aging father, a famous Parisian writer whose mind is deteriorating. Variously, his wife may still be alive, may be dead, he may be dead, the daughter may have come to move him to a nursing home, a visitor may be a neighbor or someone’s former lover, everything may be a flashback of actual events, a clouded memory of events, or may actually be happening.

In some cases, the ever fluid point of view has switched over to another when you aren’t looking and it can be several seconds or even a minute before you realize the world has changed. The confusion is the point.

The topic of aging, faulty recollections, deteriorating mental acuity and the challenge of Boomers caring for their parents make this play – as well as The Father – ripe for a South Florida production given the composition of its audiences.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design