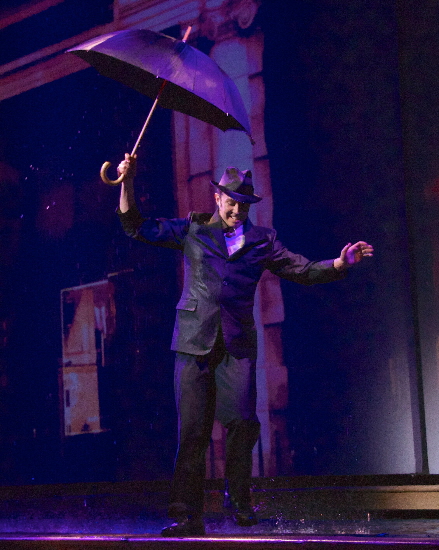

Don Lockwood (Jeremy Benton) takes a legendary stroll in The Wick Theatre’s Singin’ in the Rain Photos by Amy Pasquantonio

By John Thomason

The cinema hasn’t killed the theatre, but it’s been firing shots from the bow since the dawn of the nickelodeons. Movies have eternally been live theatre’s most tempting rival for an audience’s time, attention and pocketbook, from their (comparatively) lower ticket prices to today’s homebound ease of Redbox and streaming. This is partly why curtain speeches at more than one South Florida theatre have included expressions of gratitude for choosing a play over a movie.

That’s why it pains me that the Wick’s Singin’ in the Rain, for all of its talent and technical achievements and good cheer, offers too few reasons to experience the stage version of the definitive MGM movie musical on its own merits. It’s such a studied, careful, conservative Xeroxing of the movie that it only occasionally gives way to the woollier possibilities of the stage experience. Why choose the play over the movie when the difference is so negligible—when the show is trapped in its own celluloid amber?

The Wick is not alone: I felt much the same leaving the Maltz’s average rendition in 2009. There are many reasons for this. Betty Comden and Adolph Green, who scripted the book nearly verbatim from their own screenplay, do few favors to adventurous stage directors. It’s always been a challenge to capture the film’s Hollywood-specific enchantments in a more physical, nuts-and-bolts medium, without lavish camera movements and calculated edits.

And because the movie is so universally beloved, its adaptation is expected to hit all the recognizable, nostalgic signposts, venturing into the wild at its own peril. Twyla Tharp, who choreographed the 1985 Broadway premiere, tried to circle the square by adding a roller-skating sequence, and by supplementing the solo number “Make ‘Em Laugh” with a dance ensemble. That didn’t work either. It hasn’t been revived since.

For a property this problematic, the place where a theatre artist may be able to successfully contour around the edges is in the choreography, with the physical-comedy folderol of “Make ‘Em” Laugh,” “Good Morning” and “Moses” abounding in limitless novelty. But choreographer/director Rommy Sandhu falls back on mimicry, a safe if not particularly exciting reflex. Thus, on “Laugh,” we get the expected gags with familiar props like planks and mannequins and hidden brick walls; “Good Morning” feeds us the comfort food of the iconic raincoat bit, the matador pantomime, the exultant collapse into a tipped-over loveseat. On a purely technical level, the dancing is sensational, but there’s nothing in this show we don’t see coming.

Not that any of this affects the actors, who stay the course or better. As matinee idol Don Lockwood, Jeremy Benton—who, in profile, bears an uncanny resemblance to Jason Sudeikis—sells his title number with infectious, unfettered exuberance. (If there ever was a number that was immune from artistic re-interpretation, it’s this one; even Tharp left it alone.) His charisma is serviceable, if not quite as magnetic as we’d expect. There are few emotional challenges in the part of Don Lockwood: His personality is in his tap shoes, and their noise is joyful.

As Kathy Seldon, the ingénue love interest whom Don discovers on a park bench, Darien Crago brings a modern look and sensibility to the role, updating Debbie Reynolds’ performance with a few well-chosen dollops of smart defiance and maintaining its warmth and charm.

Most impressive are the supporting players: Courter Simmons, that perennial sidekick of the South Florida musical, delivers another dynamic expression of footloose and fancy-free dance comedy. During opening night’s “Fit as a Fiddle,” one of the production’s highlights, he dropped the bow of his instrument and proceeded to “strum” his fiddle in an act of quick thinking so clever I almost wonder if it was planned. I could say he was born to play this part, but we say that so often about Simmons that it’s starting to lose its impact.

Laura Plyler, a newcomer to the South Florida stage, hits every uncouth note—and adds a few Mae West-style innuendos of her own—as Lina Lamont, the elocutionally disadvantaged silent-film star whose career is threatened by the juggernaut of the talkies. She’s terrifically graceless in her mannerisms and delivery, and she finds a nervous breakdown in the midst of her screechy, deliberately off-key solo, “What’s Wrong With Me?,” which was added for the stage musical. But even Plyler, skilled as she is, can’t quite find the pathos and humanity that helps us empathize with her villainous character in the manner of, say, Shane Tanner’s landmark interpretation of Jed in the Wick’s Oklahama!

Timothy Shew, as the brusque producer from fictional Monumental Pictures; Cleve Asbury, as a pretentious, beret-wearing movie director; and Jane Brockman, doubling as a tabloid reporter and vocal coach, are all serviceably over-the-top. Emily Tarallo slinks libidinously in a bright-green dress in her best Cyd Charisse imitation—not her fault in a production that’s foundationally an imitation—during the ponderous “Broadway Melody” jazz number, which lands flat and feels like filler.

The show’s ambitious technical elements include the filming and projection of a handful of movie sequences, which are presented with varying success. Sandhu has a ball with an impeccably timed unsynchronized-sound gag, but the silent-film performances are broad and parodic to a fault, and the screen is unevenly divided in the middle, distorting the picture. And why is said image covered with timeworn specks and scratches? In the late 1920s, that print would have looked pristine. (While we’re on the subject of film-nerd inconsistencies, here’s one for Comden and Green: The Jazz Singer was not authorized by its studio as a fully synchronized sound film, as the script asserts; Jolson ad-libbed that now-famous aside, and the rest of the dialogue was presented with intertitles. Clearly, not all dramaturgs are cinephiles.)

There’s a similar inconsistency among the projections generally, which vary in definition and resolution quality. And since they, along with some sparse portable furnishings and a staircase, comprise the entire (uncredited) scenic design, the show’s important sense of place lacks Hollywood luster.

Furthermore, it must be said again that the Wick’s lack of live orchestration remains a hurdle to full immersion in the musical numbers.

There are worse things a show can do than go through the motions, particularly when the motions are as charming and delightful as the Wick’s Singin’ in the Rain can be. For the Wick’s case, here’s hoping the comforting balm of nostalgia is enough.

Singin’ in the Rain runs through Feb. 18 at the Wick, 7901 N. Federal Highway, Boca Raton. Tickets run $85. Call (561) 995-2333 or visit thewick.org.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design

2 Responses to The Wick Theatre’s Singin’ in the Rain Has a Familiar Patter