The “regular” South Florida theater season (ignoring that the summer is filled with offerings as well) is fully underway. Three openings last week, five this week, four in another week or so. If you don’t see a review or a feature you are looking for, it’s either already posted further down the main entry page, listed by pressing the “Reviews” tab on the teal and white rail, or it’s coming soon. There will likely be something new posted nearly every day.

The “regular” South Florida theater season (ignoring that the summer is filled with offerings as well) is fully underway. Three openings last week, five this week, four in another week or so. If you don’t see a review or a feature you are looking for, it’s either already posted further down the main entry page, listed by pressing the “Reviews” tab on the teal and white rail, or it’s coming soon. There will likely be something new posted nearly every day.

By Bill Hirschman

Confessions of a Nightingale is rooted in that dream of spending some time sitting around and listening to an eccentric genius just shoot the breeze on a quiet veranda with a fueling glass of Chablis.

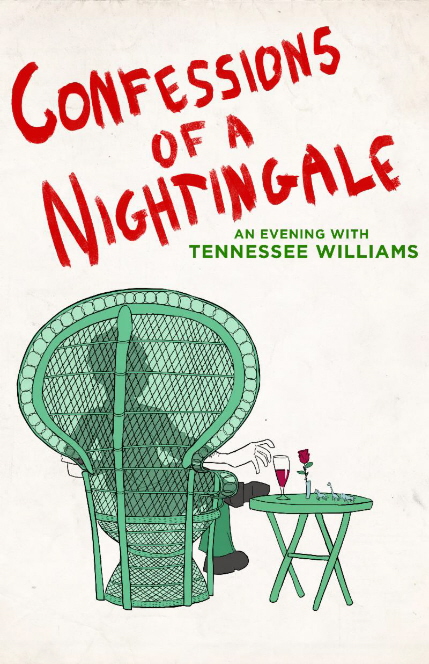

In this case, the genius is Tennessee Williams late in his career and Confessions is just such a sit down at Empire Stage where Tom roams a Key West abode with white wicker furniture and indulges his love of holding forth.

For 95 minutes, Christopher Dreeson under Jeffrey Bruce’s guidance escorts visitors through a rambling tour of his life, providing illuminating and wryly-phrased insights on his work, his sexuality, his pleasures, his guilts, his opinions on fame and death, virtually the entire scope of his well-documented existence.

Both men have worked very hard shaping this fascinating material, which is inherently rewarding, but two problems dog the production.

The 1986 play was written by the biographer-playwright Charlotte Chandler (based on interviews she had with Williams and pulling from other sources) and the late Ray Stricklyn who also starred in the original off-Broadway production. But their script has no discernable structure — narrative, chronological or emotional. Williams rambles back and forth through time and topic like a drunken guide on ADD in an uncurated gallery of vignettes from his life. That makes it hard for an audience to stay on board for an uninterrupted 95-minute haul.

The second is that Dreeson, a talented player in community theater productions, has skill and total commitment. But given the amorphous wandering nature of the script, an actor absolutely must have that rare God-given mesmerizing charisma that goes almost supernaturally beyond skill and commitment (like Williams had himself). And the genial Dreeson, as laudable as he is here, doesn’t have that, no fault of his own.

This is crucial because Dreeson doesn’t look a thing like, act like or sound like any of the audio and audio footage anyone has ever seen of Williams, other than he is tall, has a moustache, affects a consistent accent of some provenance, wears a blindingly white ice cream suit and has some fluttery posing hand gestures. So in the name of the suspension of disbelief, the audience must simply accept Dreeson’s creation on its own terms and stop looking for a visual and aural picture of Williams.

But the script’s sole virtue, and it’s a considerable one, is that Williams was an incurable storyteller and raconteur of insightful, touching, and wry raw material pulled from the marrow of his tumultuous life in which he seemed to have intersected with most of the talented and notable personalities of the era from Eugene O’Neill to Tallulah Bankhead.

Between dishing about “”Mister Edna Ferber” and telling tales that Andy Cohen would relish, Williams volunteers more about his artistic creative process than many of his contemporaries. He speaks about how his characters are, indeed, part of him, but that the women are meant to be women and the men are men, and that he draws them from both elements co-existing in his own psyche.

Along the way, Dreeson’s Williams dispenses a bottomless snifter of aphorisms like “What is straight? A line can be straight, or a street, but the human heart, oh, no, it’s curved like a road through mountains.”

Dreeson and Bruce have mastered Williams’ habit of telling some moving confessional anecdote, and then undercutting it with a seemingly off-the-cuff self-deprecating humorous capper that illustrates how he pretended to laugh off life’s tragedies when in fact they wounded him for life. It’s all here: his complicated relationship with his mother, his feelings of having betrayed his sister, his deep love beyond death for Frank Merlo.

The actor and director put across Williams’ self-lacerating honesty and martini-dry wit wrapped in a persona he constructed, much as did Truman Capote. “I drink to escape the blue devils who poke at me from under my skin,” he explains with a droll delivery and without a shred of self-pity. Or “To know me is not to love me, maybe to tolerate me.” And most telling, echoing Blanche DuBois, “The only unforgivable sin is deliberate cruelty.”

Dreeson is also comfortable enough with the script to freely interact with the audience in character. Dreeson’s Williams grins in appreciation and verbally acknowledges when one audience member laughs at one of his witticisms. Plus, he takes advantage of Empire Stage’s legendarily living room-size space by making direct contact with individual audience members by focusing directly on them with his dark eyes.

Dreeson deserves kudos for memorizing that pinball script and delivering it with a smooth grace. It requires him to bounce around from one emotion to another, again with little consistent throughline to help him build an arc.

A nod is due Ardean Landhuis’ simple but evocative recreation of a Key West home with teal shutters, straw curtains, the wicker furniture, ancient typewriter and journal books. Similarly, Nate Sykes morphs the lighting regularly to underscore elements of Williams’ peripatetic odyssey.

What comes clear in Dreeson and Bruce’s portrait is an artist who was a heroic survivor, yet bracingly honest about his flaws.

Confessions of a Nightingale plays through Nov. 11, Empire Stage, 1140 N. Flagler Drive, Fort Lauderdale (north of Sunrise just east of the railroad tracks) 8 p.m. Thursday-Saturday, 5 p.m. Sunday. Running time: 95 minutes, no intermission. Tickets $20-$30. Call (954) 678-1496 or visit www.empirestage.com.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design