By Bill Hirschman

A twinge of discomfort skips across Tarell Alvin McCraney’s open face when GableStage guru Joe Adler drops a stack of brochures in the playwright’s lap.

The advertisements trumpet McCraney’s name and depict him sitting in a bayou seemingly contemplating his art.

He escaped a troubled childhood in Liberty City to become one of the most acclaimed young playwrights on two continents. But McCraney is not comfortable being a high-profile marketing asset.

Still, he’s too much a veteran at 30 years old not to accede to the commerce of making art – or appreciate the juice it injects in his mission to lure larger, more diverse and younger audiences to see stories spun on stage.

“We want to create a lifeline” of theater, he said before rehearsals for The Brothers Size last week. “It’s important to me that theater have a life after we’re dead and gone.”

This production of The Brothers Size is a milestone in that journey.

The edition opening Saturday marks the first time he has directed his own work professionally. More important, it’s the first time a professional South Florida company has produced one of his full-length works.

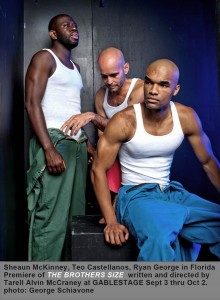

But instead of savoring a validating victory lap, he’s cool-headed and focused on helping actors Sheaun McKinney, Ryan George and his first mentor, Teo Castellanos, find the best way to tell the story.

“There’s no sense of ‘finally.’ I’m thinking that we have to have a short day (of rehearsal) tomorrow. I don’t want to wear out the actors.”

In fact, the delay in a hometown production has not been for a lack of desire, Adler said. A roster of high-powered groups like New York’s Public Theater got first dibs. Besides, Adler lobbied for a year while McCraney sought a slot when he could direct.

McCraney’s attitude is self-effacing for an International Writer in Residence at the Royal Shakespeare Company, someone tapped to join the Steppenwolf Theatre ensemble and recently consulted by a New Zealand troupe planning to perform The Brothers Size in Maori.

Boldface names in world theater have been enthralled by McCraney’s vision — a highly stylized witches’ brew of contemporary characters whose plight echoes Greek mythology and West African Yoruban folklore, but who speak in a colloquial combination of poetry and profanity. His plays visually incorporate ritualized movement, percussive music and theatrical imagery, as inspired by Alvin Ailey as Federico Garcia Lorca.

His unique voice reflects a complexity inside the man.

“Tarell can be at home in Overtown as well as at a table with Yale graduates,” Castellanos said. “What’s beautiful about Tarell is that Tarell can flow in and out of these environments and be comfortable, feel safe and accepted in these environments. The language he uses in his plays is from segments of a society that some people in Yale or Harvard or intellectuals look down upon. But he has taken colloquialisms and speech patterns and turned them into poetry.”

McCraney’s best known works are three related dramas (he bristles at the term “trilogy”) called The Brother/Sister Plays that include The Brothers Size. They all echo relationships and characteristics of his own siblings and himself.

“The plays I write come from a very selfish place. I just want to tell this story,” he said.

There’s No Place Like Home

Talking about storytelling and theater comes easily to him. Topping six feet, slender and generous with a smile, McCraney exudes affability and grace in the womb-like confines of the theater.

Castellanos, who first nurtured McCraney’s talent 15 years ago, said, “I think just every cell in his body lives and screams art…. He and I can sit and talk about art, about theater for six, eight hours…. He lives it this deeply.”

For indeed, a theater is the closest thing McCraney has to what most people consider a home. He just keeps “stuff” in boxes in various places around Miami-Dade and he loves the Ipad because he can cart around many, but hardly all, of his beloved books.

Instead of a home, he has what he calls “peripatetic periods” where he shuttles from one time zone to another.

“In June, I opened, to not much praise, American Trade in London, flew into New York to work on a workshop of a new commission by Berkeley Rep called Again & Again based on Antigone, then to Chicago to my ensemble theater Steppenwolf to do a workshop on the Book Of Job, then back to New York to workshop my play Choir Boy, an MTC (Manhattan Theatre Club) commission. After that I flew down to Miami to start rehearsal the next day.”

The rest of this year is devoted to four pending commissions to write plays. But he’ll tackle them one at a time because he can’t devote the proper attention to them otherwise. At least, he said with a giggle, “I write very fast.”

It could be worse, Castellanos said. “He’s actually not doing everything that people want him to do; he is pacing himself so that he can fully invest himself in each and every production.”

Sylvan Seidenman, another Miami mentor, joked, “I’ve threatened to put an ankle bracelet (tracker) on him.”

And yet, if he has a spiritual base, it is Miami-Dade County.

“There’s no other place that feels like home,” he told uVu photojournalist Neal Hecker. “There’s no other place that feels like I can tap right into it and understand why something is happened…. I don’t feel that way in New York; I definitely don’t feel that way in London.”

He returns frequently, if not for very long, to visit family here including his father, a godson and the graves of his grandparents in Coconut Grove. “It’s a place full of stories and familiarity.”

Bicycling to GableStage from the beach (“I never learned to drive”), McCraney said he often sees something that reminds him of a childhood. The high-dollar restaurant Prime 112 sits near the stretch of South Beach where he and his friends swam for free decades earlier.

“Every time I go by somewhere, I see what it used to be and what it is now.”

The Past Is Prologue

But Miami-Dade is also the formative crucible of a Dickensian childhood in Homestead, Liberty City, Overtown and Coconut Grove. His father left home early on. His mother fought a lengthy and eventually fatal battle with crack addiction. The family struggled with poverty while McCraney served as a surrogate parent to his siblings. Hurricane Andrew wiped out everything they owned. When his mother checked into rehab, he moved back in with his devout father who rejected the boy’s incipient homosexuality. He was bullied for being “sensitive.” He watched neighbors sink into lives of drugs and crime.

“He’s so classy and intellectual and down to earth and elegant, just elegant, that people might not realize that he didn’t have it easy,” said Patrice Bailey, dean of theater at New World School of the Arts high school in Miami.

Castellanos said, “He was blessed with incredible resiliency,” but McCraney was struggling academically.

Theater became his saving grace. He had been intrigued by it from a relatively early age. He had pursued magnet drama programs at Mays Middle, Charles Drew and South Miami High.

Then someone suggested that he join a teen program called Village South Improv run by Castellanos. The veteran actor/writer/director was fascinated by this 14-year-old.

“I thought here is a young man who is into the arts, but he has nowhere to go” to practice it. “When he auditioned for me… he didn’t do too well, but I took him anyway,” Castellanos recalled, laughing. “But pretty quickly, I think within six months to a year, you could see it…. I said, ‘Wow, he is really good.’ ”

In a painful irony, the teen helped write and perform plays for Village South in tours of halfway houses and other venues, warning about the evils of drug addiction.

By the time McCraney was accepted at the New World in 10th grade, he already had committed his life to the arts. Initially, he was interested in dance because of Castellanos’ emphasis on movement, but his father pressed him toward the more palatable field of acting.

Guidance counselor Sylvan Seidenman became his champion. Seidenman saw McCraney “had quite an intellect. His grades weren’t great, but you could see from the beginning he was a force. At New World, every kid there is an artist who is heading somewhere, but he just immediately became someone who organized this and produced that, and was just outstanding.”

McCraney’s bond with Seidenman and his wife deepened to the point that he now calls them his godparents. They helped him get into DePaul University in Chicago to study acting in 1999 when Juilliard rejected him. The couple attended all of McCraney’s performances until he graduated in 2003 and even helped him shop for housewares when he enrolled in Yale University’s prestigious master’s program in playwriting.

Using What You Have

All that back story and culture imbue his plays.

“Ties to family are very important to him despite the fact that his father was never very much of an influence, even though he lived with his father and his grandmother. But he always had an emotional tie to his mother,” Seidenman said.

“I think also the African-American culture in terms of storytelling was an important factor in his life. He listened to people preach and tell stories. I think that fascinated him.”

South Florida itself is woven in to the fabric of his work, McCraney said, notably The Brothers Size.

“The fact of the hybrid of culture that it was born out of, the language it uses from the poetic to the profane, the music that’s within it, it’s very much Miami, it’s very much South Florida, a Caribbean and a Southern Gothic mixture,” McCraney told Hecker.

He injected all that into the plot of The Brothers Size. Near a Louisiana swamp, Oshoosi Size has just been released from prison on probation, followed by a former cellmate, Elegba. He visits his straight arrow older brother, Ogun, who is trying to make a living as an automotive repairman. Ogun and the insinuating seductive Elegba battle for the younger brother’s soul as the brothers argue about freedom, tradition, sexuality and other issues that entwine and divide them. McCraney said the play depicts “the path that they forge together in rebuilding their brotherhood.”

The names are drawn from clashing deities in Yoruban legends and the relationship spins off his bond with a brother who did time in jail.

The play’s style sets it apart from traditional South Florida fare, Adler said. “It’s a unique theater experience and differs in many ways from the naturalistic, realistic theater that prevails in most parts of the country. That’s what makes it special. He has a storytelling technique that is pure and original.”

Adler, who directs most of the shows at GableStage, wanted McCraney to helm this one to see what his vision would produce, but also because Adler felt his own affinity for naturalism was not well-suited to this work. The actors break the fourth wall as if it never existed, wandering on and off a blank black stage into the auditorium, reading the stage directions aloud, interacting with the audience. McCraney joked that if someone tries to walk out, they’ll likely run into an actor who will strike up a conversation.

It’s not what GableStage audiences are accustomed to, but Adler is not worried because they embraced his non-traditional musicals, James Joyce’s The Dead and The Adding Machine.

But McCraney is concerned about “older people who have been to 90 Chekhov plays and can recite Masha’s lines by heart.”

“We’ve been battling (the audience’s expectations of) realism ever since I got here. We’ve spent hours trying to figure it out. How do we tear down the fourth wall to include the audience? I’m not trying to coddle them but I’m not trying to scare them. I hope it’s like that Bugs Bunny cartoon where they dip a toe in the water to test it.”

Still, he won’t mind if some audiences members don’t completely plug in. “Any time you create something like this, I’d rather they have that unnerved feeling rather than have them sitting there thinking about their taxes.”

Truth is, he wants to create a welcoming atmosphere that will make the audience feel comfortable and part of the experience. “I wish we could sell them some tea or give them Countrytime lemonade.”

Dream a Little Dream

If the production does find an audience, especially a younger, ethnically diverse one, it will be yet another step toward a dream McCraney has spoken about for years: creating a theater company that will nourish a broader vision of theater for upcoming generations in his hometown.

“The whole point of going away was to sort of build a cadre, a body of work and enough of a knowledge about theater to come back and create theater for Miami, specifically for Miami, and not just bringing (plays) from far away into it.”

He has plotted and continues to brainstorm intermittently with Adler, Beth Boone of Miami Light Project, the Miami-Dade Cultural Affairs Department, Castellanos and many others.

But McCraney’s dream theater would not just mount his idiosyncratic works. In fact, it would not just mount new works, a mission he sees as a little myopic.

“I want something more collaborative. Get really young directors to do older scribes. Get new translations of Iphigenia in Aulis, a really good translation of Ibsen.”

Stretching the audience’s tastes will also attract and keep local theater artists in the region. He noted that McKinney and George are local actors who moved away to find enough challenging work.

At the same time, he has a theater professional’s pragmatism to know creating a dream theater without building an audience first “is backwards. You can’t set up shop and hope people come.” He wants the proliferation of his work and similar plays to attract a new audience and help evolve the existing one.

It requires baby steps. For instance, Adler will send this production on the road in early October for heavily-discounted performances at Florida Memorial College, the historically black school in Miami Gardens.

What McCraney really wants to do is just continue telling stories, not be an administrator: “The problem with starting a theater is that I want to start it, but I don’t want to run it. No more than 5 years.”

Still, there is an appeal in the day when he isn’t living out of suitcases.

“I figure about when I get to be 45, I’ll have started two theater companies, maybe then I’ll start another chapter in my life and teach at some university.”

But not any time soon.

The Brothers Size runs Sept. 3-Oct. 2 at GableStage, at the Biltmore Hotel, 1200 Anastasia Avenue, Coral Gables. Performances are 8 p.m. Thursday-Saturday, 2 & 7 p.m. Sunday. Tickets are $37.50 to $47.50. Call (305) 445-1119 or visit www.gablestage.org

WPBT’s uVu photojournalist Neal Hecker interviewed McCraney recently on video. The interview is broken down into six parts of 2 to 4 minutes each.

Links: Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5 Part 6

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design

Pingback: Tarell Alvin McCraney and GableStage Delivers Memorable The Brothers Size | Florida Theater On Stage

Pingback: Tarell Alvin McCraney and GableStage Deliver Memorable The Brothers Size | Florida Theater On Stage