By Bill Hirschman

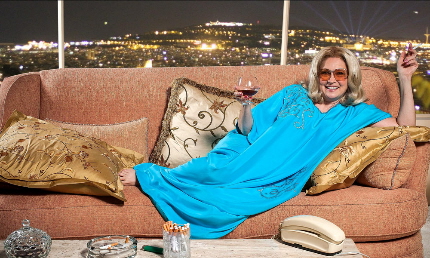

It’s a seduction. The woman lounging on the sofa with a mouth as blue as her mumu is a born storyteller and she quietly draws you under her spell until you realize you are on a rollicking log flume ride through the dog-eat-dog world of celebrity.

I’ll Eat You Last: A Chat With Sue Mengers at GableStage is an acerbically delicious cross between a gossip fest and a memoir of the legendary Hollywood super-agent of the 1970s, brought to life by the exquisite Laura Turnbull under Michael Leeds’ deft direction.

Mengers’ name may ring only the vaguest of far off bells for the current generation and a half. But equaled only by Swifty Lazar, La Mengers was an iconic grande dame whose bulldozer will and foul-mouthed but incisive wit made her as famous in the entertainment world, tabloids and trade papers as any of her clients – especially as a glass ceiling smasher. It’s a touch ironic — but would be no surprise to her — that the fame was ephemeral in a world where you are only as valuable as the gross of your last picture.

The witticisms and barbs flow smoothly in John Logan’s script like sparkling champagne, although laced with every obscenity, anatomical and sexual reference you have ever heard, just in ingenious combinations.

On her marriage to a third-rate director-writer: “On a good night we are Nick and Nora Charles; on a bad night we are Nick and Nora Charles Manson.”

Eschewing politics or any other topic at her soirees: “Henry Kissinger is only interesting to me because he is f—ing Jill St. John.”

Describing Steve McQueen’s distaste for Mengers who represented his wife Ali MacGraw: “He screwed up his face like Kermit the Frog thinking about Auschwitz” which Mengers/Turnbull illustrates.

An unpromising actress, the Jewish immigrant found her métier in the lowest echelons of a talent agency where she discovered “Why be a king, when you can be a kingmaker?”

Like any good visit and most one-actor bio-plays, there isn’t a plot so much as a jovial introduction laced with well-practiced zingers, a series of peel-away-at-the-onion anecdotes, a peek back at the path our heroine took to get here, and an elegiac coda because we always catch these figures nearing the end of their second act — with a more dour third act inevitable after the house lights return.

Her conversation rarely lasts a sentence or two without a flurry of boldface names, but she’s not dropping names to impress you (well, not quite); these are her friends, her clients, her co-workers.

It’s all a game — a blood sport with people’s emotions and relationships as chess pieces — but a game with few rules other than don’t believe half of what you hear because this is a land where genuine dreams are brought to fruition through manufactured dreams.

She tells, not quite bragging (but kind of), how she campaigned for Gene Hackman to play Popeye Doyle in The French Connection after a dozen more bankable names were considered. The story includes her parking her car so that director William Friedkin couldn’t get out of his driveway and ends with Friedkin and Hackman walking off with Oscars a year later.

Yet she describes how she fought in vain to rescue MacGraw from McQueen’s desires to make her a hausfrau and abandon her career. The denouement of that story says volumes about the mensch under the monster.

The evening benefits from the raw material of Mengers’ well-publicized life and because Logan is a skilled storyteller in film (he wrote the screenplay for Gladiator among others) and theater (the Mark Rothko play Red that was a success on this same stage a few seasons back). It’s not clear how much of Mengers’ banter is drawn from researching her actual quips and how much is Logan, but the result is scintillating. You can carp in retrospect that there isn’t much there there, sort of like theatrical Chinese food that you forget an hour later. But that may, in fact, be what Logan is saying: All the glitz and glitter are transitory and in the end almost meaningless.

One clue may be the scene when Mengers reflects that you never tell a client the truth. She reels off a list of “true” responses to a client wondering why they didn’t or can’t get a part. In a declension of several phrases, she goes from “They want someone else” to “They want someone sexier” to “You’re too old” to “Maybe it’s time to retire,” each line more ego-destroying than the one before. It reflects Hollywood as a heartlessly pragmatic place populated by idols whose egos and confidence constituting their self-worth are actually fragile.

This passage of the play comes back to haunt her and us as we realize that Mengers’ own career is on a downturn; Turnbull and Leeds allow us to see Mengers’ bonhomie desert her and then watch her resurrect it, like putting on a familiar piece of glittering costume jewelry.

We first meet Mengers in her tasteful Beverly Hills living room, decorated in pale peach and beige, with a picture window overlooking L.A. like the view from a regal throne. She is stretched out languorously on a sofa that she will not budge from until the final moments of the show – something based apparently on reality. “I’m not getting up; it’s my house,” she tells us, her guests. Her refusal to leave the sofa is a bit of a theatrical jest, but it means that Turnbull and Leeds have to keep the show from feeling physically static. How they succeed is a mystery, but they do.

Her zaftig form is draped in a bright teal caftan. She peers out from under shoulder-length blonde locks and slightly tinted glasses with a drink in one hand and the first of an endless chain of cigs and joints in the other.

It’s a few hours before one of her A List (or at the moment, B List) dinner parties that “my mother couldn’t get in.” Deals will be made and broken here because “Everything is business. This is a company town.”

More importantly, she is waiting a make-up phone call on her Princess phone from one of her oldest clients and dearest buddies, Barbra Streisand (“I knew her when she still had the other ‘ah’ “). The diva has suddenly become estranged and her lawyers have fired Mengers.

Logan slips in over and over intimations that Mengers’ world is fraying. Besides the Babs contretemps, Richard Dreyfuss cancels out of dinner with a lame excuse. We learn over time that she has been losing even her oldest and supposedly most devoted clients. We hear about the rise of a new class of corporate-minded super-agent like CAA’s Mike Ovitz who are relentlessly oriented to payday, which Mengers sees only as a way to keep score. “He’s more interested in who’s making what than in who’s screwing who.” Then she editorializes with a look of disgust. Her world is changing.

The play was written for and first acted by Bette Midler on Broadway in 2013. She worked hard to conjure Mengers not The Divine Miss M, but she could not suppress that innate wattage and outsized persona.

But Turnbull is a bona fide stage actress, easily one of the best in the state. What God didn’t give her in alchemical charisma she long ago made up for with an immense talent honed into incomparable craft that enables her to play a wide range of roles, almost always with iron and backbone beneath a conventional exterior. So her Mengers is not some caricatured sacred monster exuding oversized gusto, but a calm, self-assured human being comfortable and even proud of how she invented and built herself in a hostile world.

GableStage Producing Artistic Director Joseph Adler has once again invited a guest director in for one show and his taste in choosing relief pitchers always has been perfection. Leeds, the associate artistic director at Island City Stage who helmed the acclaimed The Timekeepers, deftly paces the changing rhythms of a play and helps Turnbull find and inhabit the core of the character. But his work is always so fine-grained and feathered in that few people in the audience notice his handiwork; they just enjoy what he has wrought.

Lyle Baskin’s stylish set is enhanced with Jodi Dellaventura’s note-perfect props and lit by Jeff Quinn whose panorama of L.A. darkens as night draw in.

The Turnbull/Leeds productions is a less raucous evening than Ms. Midler delivered (you can see parts of it on YouTube) but it’s got more heart and says more about Hollywood. It’s a fine place to sit and hear the dish.

I’ll Eat You Last runs through Aug. 30 at GableStage, 1200 Anastasia Ave., Coral Gables, inside the Biltmore Hotel. Performances 8 p.m. Thursday-Saturday, and 2 p.m. & 7 p.m. Sunday. Runs 85 minutes with no intermission. Tickets are $50 and students $15. For tickets and more information, call 305-445-1119 or visit GableStage.org

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design