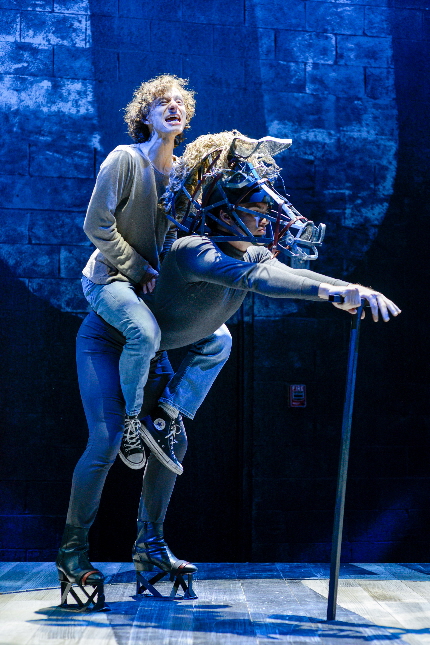

Steven Maier as the troubled Alan Strang rides Domenic Servidio as his favorite horse Nugget in Palm Beach Dramaworks’ Equus / Photos by Samantha Mighdol

By Bill Hirschman

Mere hours before the opening night of Equus at Palm Beach Dramaworks – a drama prompted by the true story of a troubled teen who blinded five horses – another troubled teen murdered 10 people and wounded 10 others in a nightmarish school shooting.

The resonances of this 45-year-old shattering drama already had been apparent to a cast rehearsing a half-hour’s drive from Parkland. But they were inescapable to Friday night’s audience hearing the echoes as the play did not so much justify but try to explain how a young person could wreak such horror.

Even more disturbing is how Peter Shaffer’s brilliant script delves into an infinitely deeper philosophical level, asking in some unique cases (not school shootings!) whether a seemingly insane young person might not actually be living a more full and fulfilling life than “normal” conventional drudges like us.

It’s not an easy work to produce, requiring complex, bravura performances and deft highly stylized theatrical staging. Two past local productions fell woefully short.

But this is Palm Beach Dramaworks, and its Equus stands among the most effective, perfectly executed productions that this company has wrought in its mission to deliver “theater to think about.”

Superb director J. Barry Lewis creates a steadily rising flood of emotions in the circling interactions of Peter Simon Hilton as a troubled psychiatrist trying to uncover the boy’s secrets in order the heal him and newcomer Steven Maier as the teenager whose mercurial interior tempest engulfs them both as the doctor persuades the boy to reenact his life in flashback scenes.

A warning: There is no gore, but the play’s thematic melding of sex, religion and violence in two unnerving scenes; foul language; justifiable nudity, and Shaffer’s refusal to end with easy answers intentionally push this work way out of some people’s comfort zones. The script is a masterpiece and this production does it full justice. But it’s decidedly not to everyone’s taste; yet everyone should be exposed to its wake up call that nothing is as simple as it seems.

Shaffer’s Amadeus is better known, but this arguably is the finest of his works deeply rooted in theatricality. For instance, the “horses” are tall, lithe, muscular men dressed in form-fitting black, standing on large elevated metal hooves and wearing skeletal cage-like horsehead masks as they prance and paw with majesty and mystical menace.

The play opens in provincial England in 1973 with the distressed musings of expert child psychiatrist Martin Dysart who reluctantly agreed to treat Alan Strang.

Dysart relates the episode by episode psychological detective story as he interviews Alan, his parents and others, to uncover the source of the boy’s horrific dysfunction. Their accounts are acted out in flashbacks during which secrets and conflicts are revealed, such as the mother’s smothering religious fervor and his father’s stolid pragmatic atheism.

Initially, Dysart seems to see the case as a logic problem. As is the case with most people, wanting to know why something like this happens is a unconscious attempt in vain to control the randomness of life and especially violence by “understanding” it.

From the moment of their first session, Alan’s gangly body and laser intense blue eyes mark him as a being from another dimension. His emotions careen wildly from anger to fear, resentment to need, combativeness to vulnerability — all of them vibrant unalloyed passions.

Dysart, on the other hand, is one of those highly-intelligent and educated English middle class professional men. He has genuine empathy for his troubled patients but his self-effacing wit conceals an ever-deepening discontent and discomfort at the deadness of his life. All that fires his banked passion is a puny fascination with classical Greek culture and mythology that invades even his dreams.

As Dysart slowly gains Alan’s trust and plays on the boy’s need to expiate, he discovers that Alan literally worships horses with an adoration whose expression on monthly midnight rides melds sacred abandon and unacknowledged sexual urges. The warring parts result in a tragic collision.

Yet as Dysart closes in on the potential to “cure” the boy, he realizes that robbing Alan of his unique zeal in order “to make him normal” may be a kind of sin when the boy’s passion and lifeforce incalculably outstrips anything that Dysart has ever felt.

As Alan comes closer to recreating the eventual eruption under Dysart’s seduction, the psychiatrist’s doubt of the rightness of his course crests as the unanswerable dilemma comes to overwhelming commandeer him as totally as Alan’s obeisance owned him.

Along the way, Shaffer explores several issues including nurture versus nature vis a vis parental responsibility in such cases, and the competing virtues of vital old pagan religions and the pent-up strictures of modern “civilized” society.

Shaffer’s script is appropriately colloquial and elemental in its language for Alan, and gloriously lyrical for Dysart as he agonizes over the growing anxiety over the abyssal difference between the flatness of his life and the luminous substance of Alan’s.

Lewis, once again, is a master at analyzing and evoking the playwright’s intent beat by beat. His staging is fluid, especially charging from flashbacks of the treatment sessions into Dysart’s venting to his confidant Hesther. But he is also undeniably responsible for a portion of the stunning performances.

The handsome smooth-speaking Hilton has visited before in Dramaworks’ Arcadia and the Maltz Jupiter Theater’s The Audience and Frost/Nixon. But the roles did not give him the well-deserved opportunity to dig so deeply into a character. Employing considerable Shakespearean credits, he masterfully embraces Shaffer’s language in the emotionally intensifying soliloquy confessions to the audience. His voice bristles with a facile brittle wit that Hilton makes clear is an ineffective bulwark against the demons growing inside him.

But the discovery is Maier who has had some experience but — almost impossible to believe— is making his first professional stage performance.

Interviewed weeks ago, Maier came across a likable, well-balanced, normal, trained young actor eager to embrace his first big break. So his absolute inhabitation of this troubled tortured soul was so complete that he was nearly unrecognizable. Every one of Alan’s steadily changing intense emotions played across his mobile face as clearly as if projected uncensored on an IMAX screen. He credibly fulfills the need near the end of each act to give himself over to an escalating tidal wave of pain and abandoned adoration. His painfully slender body is equally an instrument of angular limbs twisted every which way to further express the pungent chaos inside, whether embracing the flanks of a horse or draped over a bench.

The supporting cast is unassailable. Anne-Marie Cusson, who gave one of last season’s finest performances in Collected Stories, is the understanding Hesther. Carbonell winner Mallory Newbrough is Jill, the girl who befriends Alan at the stables they work at and entices him into the inciting encounter. John Leonard Thompson, author of so many fine Dramaworks performances, is the father, and Julie Rowe the mother who insists that the parents are not the culprits. Steve Carroll is the horses’ owner. Meredith Bartmon is a nurse and Domenic Servidio is the lead beloved horse Nugget, joined by fellow equuses Austin Carroll, Nicholas Lovalvo, Robert Richards Jr. and Frank Vomero,

Anne Mundell’s minimalist set is backed by a charcoal wall with the word Equus dominating the stage. Kirk Bookman’s evocative lighting bathes the set is a warm glow, except in flashback and surreal scenes flooded with a bright truth-telling white light. The characters were further exposed by Franne Lee’s costumes. Steve Shapiro unsettled the audience with an unearthly sound of moans that could be a demonic choir in hell. Ben Furey helped all but the British Hilton nail their accents and Lee Soroko worked with everyone especially the towering horse-actors on the frightening movements that included stamping and heads bowed to be stroked or held erect disdainfully.

Together, the crescendo of script, performance, visuals and especially Lewis’ direction, Equus is one of the highlights of this or many other seasons.

Equus plays through June 3 at Palm Beach Dramaworks, 201 Clematis St., West Palm Beach. Performances are 7:30 Wednesday-Thursday, 8 p.m. Friday-Saturday, 2 p.m. Wednesday, Saturday and Sunday. Running time 2 hours 35 minutes including one intermission. Regular individual tickets $75, student tickets $15, and Pay Your Age tickets are available for those 18-40. Tickets for educators are half price with proper ID. Call 561-514-4042 or visit palmbeachdramaworks.org.

To read a feature about the production, click here.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design

One Response to Stunning Excoriating Equus Gallops Across Dramaworks